Methodology: Introduction and overview

This section is comprised of three parts:

Part one below describes the research questions, timeline of activities and the methods employed to identify gaps and opportunities in national hate crime recording and data collection systems. It includes:

- A literature review of existing data, policy and practice frameworks relating to hate crime recording

- A workshop methodology that both supports bi-lateral and multi-lateral consultation and the co-design of graphics to present research findings

Part two uses feedback and reflections from stakeholders to evaluate the outputs of the research methodology.

Part three presents a step by step guide to activities used during the research, including national workshops and change agent interviews.

Part I: research questions, methods and timeline

Research questions:

The research stream of the Facing all the Facts project had three research questions:[1]

- What methods work to bring together public authorities (police, prosecutors, government ministries, the judiciary, etc.) and NGOs that work across all victim groups to:

- Co-describe the current situation (what data do we have right now? where is hate crime happening? to whom?)

- Co-diagnose gaps and issues (where are the gaps? who is least protected? what needs to be done?)

- Co-prioritise actions for improvement (what are the most important things that need to be done now and in the future?)

- What actions, mechanisms and principles particularly support and what undermine public authority and NGO cooperation in hate crime recording and data collection?

- What motivates and supports those at the centre of efforts to improve national systems?

Research timeline

November 2016- February 2017

- November 2016: meeting of reference group to inform and shape the research methodology.

- Created ‘assessment matrix’ based on ODIHR’s ‘Ten Practical Steps’ and key international norms and standards to structure information about how hate crimes are recorded and how data is collected across public authorities, with a focus on the police, prosecution service, courts and relevant ministries. The matrix included a description of CSO involvement in all aspects of hate crime recording and monitoring (see Annex one). National partners took the lead in completing the matrix to the best of their knowledge also liaising with the relevant national stakeholders.

- Developed interview guides for ‘change agents’. Partners started to identify participants for interviews.

- Started to develop workshop agenda and methodology.

March – May 2017

- Finalised workshop methodology

- Planned 6 national workshops to map gaps and opportunities in data collection in partner countries.

May – June 2017

- Held workshops in Athens, Budapest, Rome and Dublin

- Interviewed 20 change agents in above countries (5 per country)

July – October 2017

- Reviewed findings from workshops, transcribed interviews and conducted theme analysis

- Held workshop in Madrid and interviewed 5 change agents

November 2017

- Held England and Wales workshop in Leeds

- Interviewed 5 change agents

December 2017 – April 2018

- Reviewed findings from Madrid and Leeds workshops; transcribed change agent interviews; conducted theme analysis.

- Finalised ‘Journey of a hate crime graphic’

- Finalised ‘systems map’ prototype

- Produced first draft national reports

- Planned consultation workshops

- Conducted online learning development for workstream two

May 2018

- Held consultation workshop in Rome

- Revised systems map and report based on workshop outcomes

June – August 2018

- Planned remaining consultation workshops

- Finalised reports for consultatio

September-December 2018

- Held consultation workshops in Madrid, Athens, Budapest, Dublin and London

- Revised systems maps and reports based on workshop outcomes

- Drafted European report

- Facing all the Facts conference

December 2018- December 2019

- Finalised and published all outputs

Summary of outputs:

Eight graphics:

- ‘Journey of a Hate Crime Case’ – depicting the hate crime recording and data collection process from the victim perspective. The graphic illustrates the data and information that should be recorded and collected, the key stakeholders and the consequences of not recording (including English, Hungarian, Greek, Italian and Spanish versions).

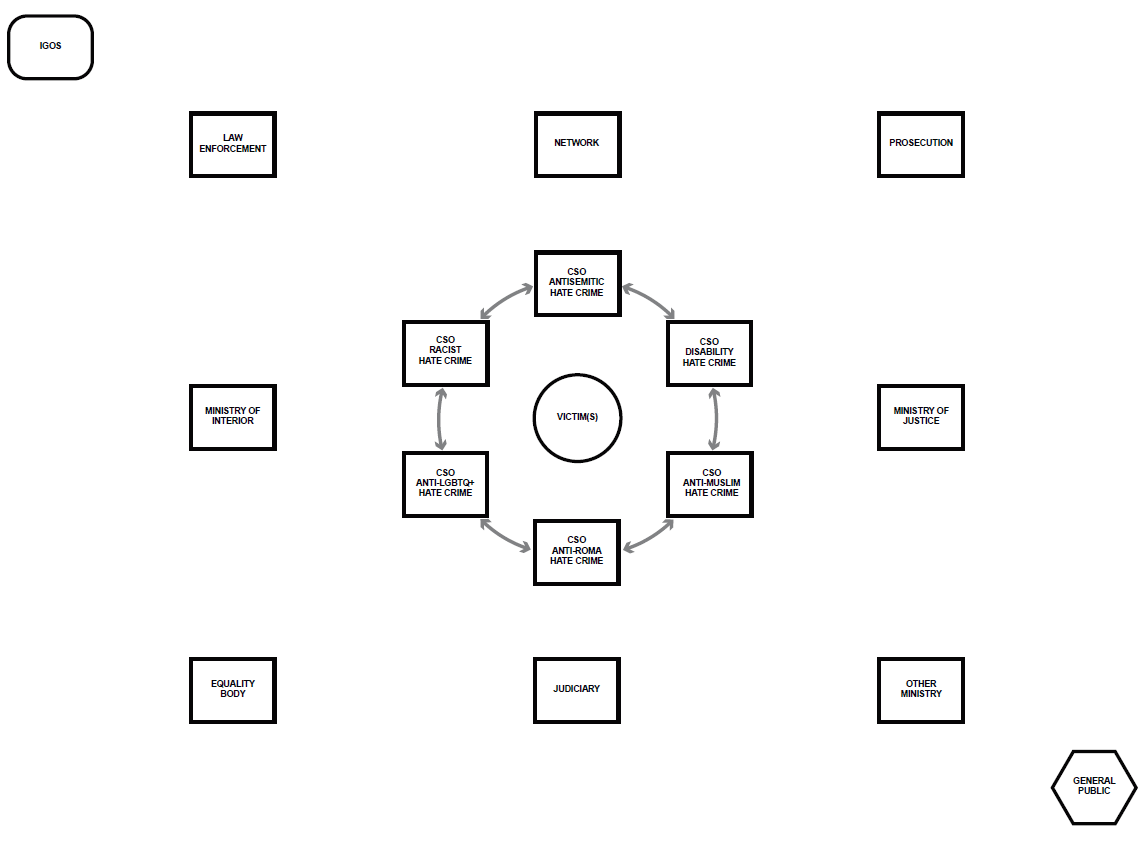

- Six national ‘systems maps’ (England and Wales, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy and Spain) and one prototype – presenting the key stakeholders involved in the ‘system’ of hate crime recording and data collection and describing relationships across the system as ‘red’, ‘amber’ or ‘green’.

Six national reports

- Reports on England and Wales, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Spain – set out the background of national developments on hate crime recording and data collection, emerging themes from interviews with ‘change agents’, analysis of country systems maps and recommendations for action.

One European report

- Sets out emerging themes across the six countries involved in the research and makes recommendations aimed at European policy makers and practitioners.

Two ‘How to’ guides for group work at the national, regional/ local level:

- Mapping the journey of a hate crime case from the victim perspective and identifying strengths and weaknesses in national processes.

- Mapping the key stakeholders and most important relationships in national hate crime recording and data collection systems; co-diagnosing strengths and weaknesses and co-prioritising actions for improvement.

One comprehensive self-assessment framework based on all relevant norms and standards on hate crime reporting, recording and data collection.

Online learning on hate crime recording and data collection for decision-makers

- 1-2 hour online course that draws on learning from research outputs including the Journey and systems graphics and good practice case studies to support learners to explore principles of hate crime recording and data collection, relevant international norms and standards, and how to strengthen meaningful and effective cooperation across institutional boundaries.

Innovative research methodology

The project combined traditional research methods, such as interviews and desk research, with an innovative combination of methods drawn from participatory research and design research.[2]

Desk research underpinned the production of a set of standards derived from existing normative obligations and commitments on hate crime reporting, recording and data collection that were used in participatory activities to highlight to gaps and opportunities for improvement in national ‘systems’.[3]

Interviews with ‘change agents’ were used to understand what factors support or undermine cooperation between CSOs and public authorities around hate crime reporting and recording (at least 5 per project country, 32 in total).

Because this multi-agency, multi-country project specifically aimed to understand and influence the national ‘systems’ around hate crime during the course of the project and beyond, it was essential to adopt participatory research methods, involving national stakeholders in every aspect of the project.[4] Significant effort was put into identifying and involving stakeholders with a role in hate crime reporting, recording and data collection from across the public authority and civil society perspectives in all aspects of the research, with the twin hopes that their input produces rich and legitimate findings and that the experience enriches their own practice and decision-making. Those stakeholders were engaged in participatory workshops that, among others things, fed directly into the project graphics. Workshops were designed to engender an interactive, non-hierarchical and safe space, so that participants could take a critical yet solution-focused approach to the activities.

However, involving many stakeholders that come from differing – even contradictory – perspectives, and who operate in divergent contexts, risks producing research outputs that lack focus and coherence.[5] To mitigate these risks, the project also drew on methods from design research. Specifically, it made ideas visible and tangible in order to aid communication and experimentation.[6] For example, during national participatory workshops, stakeholders negotiated with each other to build prototypes, physically representing what information on hate crime is being reported and recorded, by whom and how effectively. In this way, stakeholder participants were prompted and facilitated to enter a ‘design-mode’; to look again, with a ‘critical’, ‘imaginative’ and ‘practical’ eye, at a topic with which they were very familiar; and together to explore the ‘actual [and] potential system within which hate crime is reported and recorded’ in a ‘structured yet free’ space.[7]

In a further design-driven step, the results of these participatory activities were synthesised with the traditional research results to produce two sets of formal project graphics, which then fed back into additional participatory activities. One graphic, ‘journey of a hate crime case’, was designed to make visible, from the perspective of a victim, the stages at which hate crime cases may or may not be reported and/or recorded, and the key actors involved. The second set of graphics, ‘national system’ maps, aimed to make visible both the key national actors (public authorities and CSOs) around hate crime reporting, recording and analysis; and the effectiveness of the relationships between those actors.

Together these traditional, participatory and design-driven methods produced specific commitments at the national level, as well as thematic findings to influence international frameworks and action.

The rest of this document describes the research in more detail and critically reviews the strengths and weaknesses of the research methods.

Stage one

First, the issues that the research aimed to explore were set out (see objectives above). Second, action was taken to plan and conduct workshops, interviews and desk research (see above timeline). Third, themes and emerging questions were reflected upon with national partners, leading to stage two.

Stage two

Reflection on emerging themes and findings led to the distillation of two key concepts: that hate crime recording and data collection is a process that (should be) supported by a system of relationships across institutional boundaries, of varying strengths.

Stage two involved designing and testing two graphics presenting the process and system concepts. The first graphic, ‘The Journey of a Hate crime’, depicts a victim-focused process of what should be recorded, by whom and why along with the consequences of not recording.[8] The second graphic, the ‘systems map’ depicts the main actors with responsibilities to record hate crimes as a system of relationships of varying strength. A workshop methodology was developed in parallel to allow the same stakeholders to apply the ‘journey’ and ‘systems map’ approach in order to co-describe the current situation, co-diagnose problems and opportunities and co-prioritise recommendations for improvement in their national contexts.[9] A draft online systems map was shared for consultation and feedback, allowing for a second stage of reflection in the project.[10]

The stage two consultation workshops allowed for corrections of fact to the systems maps, and for critical feedback about the methodology itself. [11]

During the stage two consultation workshops, agreement was achieved on at least one recommendation per country. This method contributed to building consensus and shared understandings across key stakeholders at the national level. In this way, the design-driven participatory methodology allowed key stakeholders to use, influence and give legitimacy to the design of the final research outputs.[12] Further reflection on the most common recommendations is provided in the main body of the European report.

Feedback during the stage two national consultation workshops led to a complete review of the systems map methodology. Workshop participants in several contexts pointed out that the criteria for assessing national contexts was insufficiently clear and transparent. In line with design-driven participatory research principles, the self-assessment framework was revised to explicitly link to criteria, backed up by international norms, standards and guidance, and consulted on with partners, other national stakeholders, and, informally, with colleagues from international organisations.

During the second and final reflection phase, the graphics were finalised, national findings were brought together in 6 reports, and thematic findings across the project were set out in the European report. Specific principles, concepts and practices of connection were identified, which added context to the process and systems findings, creating a comprehensive presentation of what supports connection and progress in understanding and addressing gaps and opportunities in national hate crime recording approaches.

Understanding national systems maps

The primary purpose of the national ‘systems’[13] maps is to:

- Represent those actors at the national level that play a key role in hate crime recording and data collection

- Describe the strength of relationships across the system based on specific criteria.

A secondary, or contextual purpose was to explore whether these ‘systems maps’ could represent and develop the shared idea that all stakeholders (including monitoring CSOs) are equal partners in this system, thus supporting the instigation and development of ‘cross-boundary’, sustained cooperation at the national level.

Explanation of key actors in national ‘systems’

As with the Journey graphic, it was a pre-requisite of the design to have all relevant stakeholders on one page, with a victim focus and connected to each other. While some contexts have additional stakeholders represented on the map, those listed below are on all maps. This section explains the general role of each of the actors on the systems maps and should be read in conjunction with the self-assessment framework.

Victim(s) – keeping with the ‘journey of a hate crime case’ graphic, the victim is placed at the centre of the ‘system’ symbolising the most important focus, and representing the fact that if victims don’t report, there is no hate crime to record.

CSOs monitoring key types of hate crime – these icons comprise the first ‘layer’ of recording, and represent civil society organisations that should and do record hate crime. To be included in the graphic, the CSO normally needs to have a clear methodology for hate crime recording and data collection that significantly relies on direct victim and/or witness reports. The extent to which they share the information and raise awareness of their service with victims is reflected in the colour of the relationships (see below).

Law enforcement and criminal justice agencies – Police/ law enforcement – in addition to CSOs, the police are the most likely institution to receive reports from victims and witnesses and (should) have the strongest links with the prosecution service, other agencies and government ministries. Even if they conduct very limited hate crime recording and data collection, they are included in each graphic, because they are the first point of contact for most victims and, under international norms and standards, have the most significant responsibility to record hate crimes. In several maps, this icon represents a broad range of agencies that fit within the overall category of ‘law enforcement’. This might require further explanatory text or more than one icon for law enforcement.

Prosecution service – prosecution services have obligations, under international norms and standards, to record information and data about hate crimes, and have an important relationship with law enforcement. They are therefore represented on all systems maps. In some countries the prosecution service is part of the judiciary.

Courts/judiciary – the courts have obligations – under international norms and standards – to record data and information about hate crimes, and are therefore represented on all systems maps. It is their data that (should) communicate(s) whether hate crime laws have been applied. In some contexts, the judiciary and prosecution service are connected.

Government ministries – in most countries, ministries of interior and justice are involved in collating and reviewing hate crime data that has been recorded by law enforcement and criminal justice agencies. In some countries other ministries such as the ministry of foreign affairs, ministries with policy responsibilities in relation to migration and integration, or the prime minister’s office also play an active role.

More often than not, it is ministries that set broader hate crime reporting, recording and data collection policy, which determines the specific powers that the police and other agencies have to record hate crimes. In other words, they set the frameworks that allow data sharing and cooperation to develop from ad-hoc to systematic. It is also usually these bodies that are consulted by parliaments for data when hate crime laws are being proposed, debated and revised. As with law enforcement, there are challenges in showing the granularity and complexity of those units and departments within ministries that play an active role in recording and data collection.

Intergovernmental organisations and agencies (IGOs) – IGOs request and receive a significant amount of data and information on hate crime from national authorities. In the case of some IGOs, national governments have specific commitments to share data. While IGOs are bound by fewer obligations and commitments than national authorities, they have committed to share data and information and engage and involve national stakeholders in networks, policy development and capacity building activities.

The general public – the general public are witness to, and in some cases, victims of hate crime. They are also a key target audience for efforts to raise awareness about the problem and what is being done to understand and address it.[14] The extent to which ‘hate crime’ enters the national consciousness as a problem of national concern that needs to be addressed can determine the degree of political attention and action it receives.

The self-assessment framework

Click here to view the entire self-assessment framework.

« FINDINGS IX BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SELF-ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK »

[1] In terms of its conceptual scope, the research focused on hate crime recording and data collection, and excluded a consideration of hate speech and discrimination. This was because there was a need to focus time and resources on developing the experimental aspects of the methodology such as the workshops and graphics. International and national norms, standards and practice on recording and collecting data on hate speech and discrimination are as detailed and complex as those relating to hate crime. Including these areas within the methodology risked an over-broad research focus that would have been unachievable in the available time.

[2] A detailed academic analysis of the methodology, including the lessons to be drawn for academic (especially socio-legal) and policy research, is set out in Perry-Kessaris and Perry (2019).

[3] See International Standards section below

[4] Bergold and Thomas 2012; Chevalier and Buckles 2013.

[5] Bergold and Thomas 2012 paras 2, 42 and 50.

[6] Perry-Kessaris 2019 and forthcoming 2020.

[7] Perry and Perry-Kessaris, 2020

[8] See main report for full presentation of the findings presented in the Journey of a Hate Crime.

[9] See part III below for a ‘how-to’ guide.

[10] The Facing All the Facts’ Multi-Media conference on 11 December was another opportunity to share and reflect on findings both during the first plenary session and a parallel workshop. Insert link to film and interim findings document.

[11] This proved to be an important step to include in the project because there were gaps in some systems maps. For example, in some contexts, partners mainly relied on the information that was in the public domain to assess the strength of relationships across the ‘system’. During the workshop, stakeholders stressed the importance of directly approaching institutions and agencies for confirmation of current approaches and seeking evidence for this.

[12] On the other hand, it could be counterproductive to put stakeholders ‘on the spot’ to agree specific recommendations. In some contexts it was more constructive to approach lead stakeholders separately for their view on recommendations pertaining to them.

[13] The word ‘system’ is usually used in a narrow sense referring to the ‘official’ systems that record and collect data, such as the police, prosecution services and relevant government ministries. Research findings suggest that the meaning and use of the term should be expanded to include those CSOs that record and collect data on hate crime and/or support victims.

[14] However, it is important to note that including ‘the general public’ presented methodological incongruity. Apart from being possible witnesses to hate crime, they are not recorders or collectors of hate crime data. In addition, the term ‘general public’ hosts hugely diverse people from those community groups that are the targets of hate crime and work closely with victims to those that might even be hostile to the ‘agenda’. Including the general public led to discussions about whether other bodies such as ‘the media’ or ‘parliament’ should also be included. This point should be further examined in future research.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme