Perry, J. Tamás Dombos, T., Kozáry, A (2019) Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Hungary. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.

Download the full report in PDF here.

Introduction

If we are to understand hate crime[1], support victims and reduce and prevent the problem, there are some basic questions that need to be answered:

- How many hate crimes are taking place? Who are the people most affected? What is the impact? How good is the response from the police? Are cases getting investigated and prosecuted? Are the courts applying hate crime laws? Are victims getting access to safety, justice and the support they need?

While ‘official’ hate crime data, usually provided by police reports, are the most cited source for answers to these questions, they only tell a small part of this complex story. Understanding what happens to cases as they are investigated, prosecuted and sentenced requires a shared approach with cooperation across government agencies and ministries with responsibilities in this area, however, the necessary mechanisms and partnerships are often not in place. Reports and information captured by civil society organisations (CSOs) can provide crucial parts of the jigsaw, yet connection across public authority- civil society ‘divides’ is even more limited.

The Facing all the Facts project used interactive workshop methods, in-depth interviews, graphic design and desk research to understand and assess frameworks and actions that support hate crime reporting, recording and data collection across a ‘system’ of public authorities and CSOs.[2] Researchers adopted a participatory research methodology and worked directly with those at the centre of national efforts to improve hate crime reporting, recording and data collection to explore the hypothesis that stronger relationships lead to better data and information about hate crime and therefore better outcomes for victims and communities.

What was found is that a range of factors are key to progress in this area, including the:

- strength and comprehensiveness of the international normative framework that influences national approaches to reporting, recording and data collection;

- technical capacity to actually record information and share with other parts of the system;

- existence of an underlying and inclusive policy framework at the national level;

- work of individual ‘change agents’ and the degree to which they are politically supported;

- skills and available resources of those civil society organisations that conduct recording, monitoring and advocacy.

The research found that each national context presents a different picture, and none is fully comprehensive or balanced.

This national report aims to describe the context and current picture of hate crime reporting, recording and data collection in Hungary and to present practical, achievable recommendations for improvement. It is hoped that national stakeholders can build on its findings to further understand and effectively address the painful and stubborn problem of hate crime in Hungary.

It is recommended that this report is read in conjunction with the European Report which brings together themes from across the six national contexts, tells the stories of good practice and includes practical recommendations for improvements at the European level. Readers should also refer to the Methodology section of the European Report that sets out how the research was designed and carried out in detail.

How did we carry out this research?

The research stream of the Facing all the Facts project had three research questions:[3]

- What methods work to bring together public authorities (police, prosecutors, government ministries, the judiciary, etc.) and NGOs that work across all victim groups to:

- co-describe the current situation (what data do we have right now? where is hate crime happening? to whom?)

- co-diagnose gaps and issues (where are the gaps? who is least protected? what needs to be done?), and;

- co-prioritise actions for improvement (what are the most important things that need to be done now and in the future?).

- What actions, mechanisms and principles particularly support or undermine public authority and NGO cooperation in hate crime recording and data collection?

- What motivates and supports those at the centre of efforts to improve national systems?

The project combined traditional research methods, such as interviews and desk research, with an innovative combination of methods drawn from participatory research and design research.[4]

The following activities were conducted:

- liaised with relevant colleagues to complete an overview of current hate crime reporting, recording and data collection processes and actions at the national level, based on a pre-prepared template;[5]

- identified key people from key agencies, ministries and organisations at the national level to take part in a workshop to map gaps and opportunities for improving hate crime reporting, recording and data collection.[6] This took place in Budapest on 24 May 2017.

- arranged for in-depth interviews with five people who have been at the heart of efforts to improve reporting, recording and data collection at the national level to gain their insights into our research questions.

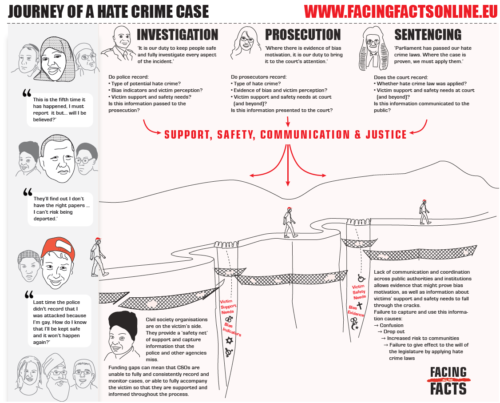

Following the first phase of the research, the lead researcher synthesised existing norms and standards on hate crime to create a self-assessment framework, which was used to develop national systems maps describing how hate crimes are registered, how data is collected and used and an assessment of the strength of individual relationships across the system. A graphic designer worked with researchers to create visual representations of the Journey of a Hate Crime Case [see below] and national Systems Maps (See ‘Mapping the hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’ in Hungary’ below). Instead of using resources to launch the national report, it was decided that more connection and momentum would be generated at the national level, and a more accurate and meaningful final report would be produced, by directly consulting on the findings and recommendations during a second interactive workshop which was held in Budapest, 19 October, 2018

During the final phase, the researchers reviewed and revised the final reports and systems maps, seeking input and clarification with stakeholders, as needed. In addition, themes from this and other national reports were brought together and critically examined in the final, European Report.

Background

The political, legal, social and technical aspects of hate crime in Hungary have been well documented by the Working Group Against Hate Crimes since 2012. The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, focused on Greece and Hungary in a recent report and Amnesty International and Human Rights First regularly report on the country. This report will not repeat or rehearse this rich set of information on Hungary; its focus is on hate crime recording and monitoring. It explores the efforts of key actors to implement and improve hate crime recording and data collection processes that are victim focused and that prioritise collaboration across NGOs and between NGOs and the Hungarian state.

The journey of a hate crime

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[19]

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[19]

The Journey graphic conveys the shared knowledge and experience generated from this exercise. From the legal perspective, it confirms the core problem articulated by Schweppe, Haynes and Walters where, ‘rather than the hate element being communicated forward and impacting the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of the case, it is often “disappeared” or “filtered out” from the process.’[20],[21] It also conveys the complex set of experiences, duties, factors and stakeholders that come into play in efforts to evidence and map the victim experience through key points of reporting, recording and data collection. The police officer, prosecutor, judge and CSO support worker are shown as each being essential to capturing and acting on key information about the victim experience of hate, hostility and bias crime, and their safety and support needs. International norms and standards[22] are the basis for key questions about what information and data is and should be captured.

The reasons why victims do not engage with the police and the criminal justice process are conveyed along with the potential loneliness and confusion of those who do. The professional perspective and attitude of criminal justice professionals that are necessary for a successful journey are presented.[23] NGOs are shown as an essential, if fragile, ‘safety net’, which is a source of information and support to victims across the system, and plays a role in bringing evidence of bias motivation to the attention of the police and the prosecution service.

The Journey communicates the normative idea that hate crime recording and data collection starts with a victim reporting an incident, and should be followed by a case progressing through the set stages of investigation, prosecution and sentencing, determined by a national criminal justice process, during which crucial data about bias, safety and security should be captured, used and published by key stakeholders. The graphic also illustrates the reality that victims do not want to report, key information about bias indicators and evidence and victims’ safety and support needs is missed or falls through the cracks created by technical limitations, and institutional boundaries and incompatibilities. It is also clear that CSOs play a central yet under-valued and under-resourced role.

As in most contexts, there is serious under-reporting of hate crimes to the police and to NGOs in Hungary. There are also gaps in provision, support and information for victims, leading to drop out and poor outcomes. The following particular points came up in this research:

- First responders can still fail to recognise hate crime, forcing victims to make a separate report. If victims do not make a separate report, the crime never enters the system;

- Bias indicators are recorded in police reports sporadically, not systematically;

- While the police personally meet the victim and can have a personal impression about the victim, the prosecutor does not. It might be obvious to the police that a victim belongs to a protected social group, yet the prosecutor may not accept their perception, thus losing a key bias indicator. This situation can be more frequent in hate crimes involving LGBT+ targets.

- There is no connection made between crime statistics and sentencing data. As such it is currently impossible to trace cases throughout the criminal justice system.

These points are addressed in more detail when we look at Hungary’s ‘system’ of hate crime recording and data collection below.

Click here to download the Journey in Hungarian.

Mapping the hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’ in Hungary

The ‘linear’ criminal justice process presented in the Journey graphic is shaped by a broader system of connections and relationships that needs to be taken into account. Extensive work and continuous consultation produced a victim-focused framework and methodology, based on an explicit list of international norms and standards that seeks to support an inclusive and victim-focused assessment of the national situation, based on a concept of relationships. It integrates a consideration of evidence of CSO-public authority cooperation on hate crime recording and data collection as well as evidence relating to the quality of CSO efforts to directly record and monitor hate crimes against the communities they support and represent.[24] It aims to go beyond, yet complement existing approaches such as OSCE-ODIHR’s Key Observations framework and its INFAHCT Programme.[25] The systems map also serve as a tool support all stakeholders in a workshop or other interactive setting to co-describe current hate crime recording and data collection systems; co-diagnose its strengths and weaknesses and co-prioritise actions for improvement.[26]

The interactive ‘Systems map’ below is best viewed in full screen mode (click on the icon in the top right hand corner of the map).

Click on the ‘+’ icons for an evidence-based explanation of the colour-coded relationship, based on international norms and standards.

Or download ‘Self-assessment grid on hate crime recording and data collection, framed by international norms and standards – HUNGARY (PDF 326KB)‘

Overview and Commentary

There is no national framework supporting a comprehensive approach to hate crime recording and data collection. For example, the government’s National Crime Prevention Strategy and Action Plan do not include any specific measure relating to countering hate crime. In a welcome development, on 1 July 2018 a flag was introduced to improve the system and allow the tracking of hate crime cases and to capture specific protected characteristics. However, there are still gaps that undermine the quality of the data. There was a significant increase in recorded hate crimes in 2017, however, it is unclear whether this is due to improved recording or a change in recording policy and practice.

The Working Group Against Hate Crime is a key driver in hate crime recording and data collection in Hungary. It has the strongest relationships across the system, including with public authorities, affected communities, IGOs and the general public. The police have stronger frameworks to record and collect data on hate crime, which raises challenges when connecting with the more limited framework and capacity of the prosecution service and the courts.

The key stakeholders involved in hate crime recording and data collection in Hungary have strong relationships with IGOs and regularly share data and take part in international networks. There is a tendency for public authorities to share more detailed data and information with IGOs than with the general public of Hungary. Publicly available data is not broken down in an accessible way, making it very difficult for affected communities to find out the nature and prevalence of hate crime and how the government is responding.

Communities affected by disability hate crime are very under-served by the system. The recent demise of specialist organisations supporting Roma communities has also had negative effects.

National policy and practice context

The technicalities of hate crime recording and data collection take place in a dynamic social and political context. As set out in the above timeline, there have been significant milestones in Hungary’s journey of understanding and responding to hate crime. The serial murders of Roma people in 2008-2009 and the frequent intimidation of Roma communities made the danger of the far right and the problem of hate crime impossible to ignore. Failures to protect participants in multiple Pride events galvanised advocacy efforts to expose and improve state responses, receiving international attention. Several judgments against the Hungarian government by the European Court of Human Rights further enhanced international scrutiny.

Partly in response to these significant events, Hungary’s hate crime laws are relatively comprehensive, a national network of specialist police has been established, the Working Group Against Hate Crime has produced high quality data reports and key successes in advocacy, and there has been specific progress in cooperation across CSO and public authority ‘divides’.

However, overall, this journey might be best described as ‘one step forward and two steps back’ and takes place against a backdrop of significant obstacles that render it fragile and under threat. There is no national policy framework that commits ministries and criminal justice agencies to a comprehensive approach to understanding and addressing hate crime and the constant presence of the far-right is a key undermining factor. As expressed by one interviewee,

‘we are competing with the … high profile of the far right, which is quite developed …in the national journey of understanding and addressing hate crime’.[27]

The connection between political rhetoric and hostility against common targets of hate crime in Hungary was alluded to by several interviewees. The WGAHC’s report to the Universal Periodic Review in 2015 highlighted the Hungarian Government’s ‘national consultation on immigration and terrorism’ as risking, ‘stigmatising asylum-seekers as welfare migrants and a national security threat’.[28]

The Hungarian government’s targeting of NGOs that receive funding from outside Hungary, including NGOs that are active in monitoring hate crime and supporting victims is an additional challenge.[29] One interviewee remarked,

‘[those NGOs] are the ones who believe and fight on a daily basis for our European values and about being citizens and human rights. I personally think that they are taking over the role of the state in some cases, for example when they are representing victims and in some cases vulnerable victims, these are the state’s responsibilities and I don’t think that hostility is the response… but rather the state should listen to them and possibly because they are doing the state a favour or overtaking state functions they should either operate hand in hand or even finance these NGOs.’[30]

One interviewee was very concerned that the lack of official data on hate crime, combined with a hostile political environment can give decision makers the excuse to stop academic programmes on hate crime and other important work to understand and respond to hate crime in Hungary.[31]

General problems with Hungary’s crime statistics are likely to undermine confidence in its hate crime statistics. As explained by one interviewee, ‘Interestingly in Hungary, crime statistics are [of] very bad quality but they are taken quite seriously.’[32] As in other contexts, a rise in recorded crime is not welcomed as a positive development, even in the face of evidence that crime – especially hate crime – is significantly under reported. At the operational level, higher crime figures can have negative implications in relation to officers’ career progression and how the senior leadership is perceived. The same interviewee, explained,

‘We always try to tell them: now, the only message that the data sends out is that you are not doing your job, basically. At least increase it up to a few hundred because it’s credible. Now it’s [not] credible and that’s it, no one takes it seriously… We already have three Strasbourg cases on hate crime and the NGOs put out all this data’.[33]

Despite these challenges, there is strong evidence of effective and respectful cooperation between CSOs specialist in hate crime monitoring and the police. Aspects of this work illustrate that specific goals can be achieved through practical, technical and victim-focused cooperation at the working level even in hostile political contexts with constant resource limitations. These are examined in more detail below.

A focus on CSO-police cooperation

One way of describing police-NGO cooperation in Hungary is an openness to closed-door cooperation. Relationships and significant expertise have been developed over time, yet, perhaps partly due to the challenging political context described above, cooperation usually takes place under the political radar.

The national police hate crime network, established in 2012 and led by a national coordinator, serves as a ‘form of supervision in the police system’, and directly supports cooperation with the WGAHC.[34] There are police hate crime leads at the county level whom NGOs can contact, and six-monthly meetings between the WGAHC and police authorities that review ongoing issues relating to hate crime training, recording and police investigation. Interviewees from a range of perspectives expressed the view that cooperation on training and victim support has increased the knowledge of the police and has been a constructive form of cooperation. This was also a theme reiterated during the workshop.[35] One interviewee commented on the centrality of the police hate crime coordinator network: ‘it is essential to have working level contacts at city and regional levels… it creates a clear responsibility’.[36]

The role of the WGAHC and civil society organisations more generally was acknowledged by the police, “What civil society brings from the point of view of the victim, what the police brings from the investigative side, those two together can make the fight against hate crimes successful.”[37] The interviewee also commented that CSO data is often richer as it can capture more information about bias indicators and unreported crime than police systems. While acknowledging that it isn’t possible for police systems to incorporate NGO data, she explained that she ‘personally [tries] to get to know such data’. More broadly the role of NGOs in providing essential support to victims, legally and in other ways was also acknowledged.

Several interviewees remarked that the police were specifically open to CSO input on training, developing guidance on bias indicators, and specific support on particular cases. One interviewee who has significant experience in police training pointed out that regular two-day trainings on hate crime have positively affected relationships between police and NGOs pointing out that constructive conversations with police at the station when supporting a victim to report are more likely if you have already met in the training room.[38]

Specific examples given by the national hate crime coordinator for the police illustrate the concrete and positive aspects of cooperation, ‘We work together with civil society organisations in the framework of the Working Group Against Hate Crimes. If we take the list of bias indicators or the processing of sensitive data, this Working Group works very well. We organise case study sessions to look at closed investigations: they call our attention to their concerns, how – from the point of view of the victim – we could have been more successful. This is all very constructive, with the aim to help.’ These examples are looked at in more detail below.

While not a member of the WGAHC, the Action and Protection Foundation have also played an active role in raising awareness about antisemitic crime in Hungary and have worked with the National University for Public Service on developing its hate crime curriculum. They are the only CSO in Hungary actively working on the issue of hate crimes that receives significant funding from the government.

Cooperation in practice: sparking and continuing connection

Originally, the police and WGAHC decided to meet on a 6-monthly basis between the police in response to NGOs criticism of how specific cases were being handled. It was agreed that a ‘closed door’ forum was needed to discuss these cases directly with those involved. One case per six months was to be chosen and discussed directly with the police officers involved. The approach was explained by one interviewee, ‘let’s discuss what the problems you saw were and why the police did it like that, with the understanding that this is going to be confidential and we are not going to go to the media about what was discussed.’[39]

The forum shifted its focus onto other issues, including developing a list of bias indicators. In 2015, following the publication of the ‘24 Cases’ report,[40] the WGAHC, the police and the prosecution service agreed that a concise list of indicators to help the identification of hate crimes would be a useful tool to address the shortcomings identified in the report. The WGAHC took the lead and drafted a list of indicators based on a careful consideration of various international examples.[41] In January 2016 the list was circulated for comments among police, prosecution, judiciary, victim support service, lawyers and academic institutions.[42] The draft was revised and shared with the police in 2016. It was agreed to make a shorter, two page version of the list[43] and a four page version[44] with a third column providing examples to the indicators.[45] The lists were finalized, disseminated to stakeholders and published in November 2016 on the Working Group’s website. The police agreed to use the materials in trainings and upload it to the intranet of the police. This was done in March 2018.

In the process of developing the bias indicator lists, the issue of how to collect sensitive data as part of investigations arose. Questions included, can the police ask direct questions on the victims’ belonging to a certain social group? Can the police record their own assessment whether the victim is likely to be perceived as belonging to a certain social group (based on widespread stereotypes), etc. As a result, the WGAHC took the lead in preparing a manual harmonizing investigative requirements with data protection considerations, and a list of suggested interview questions to use for such sensitive matters. The manual was then approved by the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information, and was discussed at a conference co-organized by the Working Group, NUPS and the hate crimes network in November 2017. The list of indictors and the most important provisions of the manual have been incorporated into the protocol issued by the National Chief of Police.

More recently, the Hungarian Police have endorsed the reporting platform UNI-FORM,[46] which is coordinated by the Háttér Society. The application allows for direct reporting of hate crimes by victims and others to the police. The two bodies are in discussions about a Memorandum of Understanding on its operation.

These three examples illustrate several important features that are common in efforts to work across public authority-CSO divides for the benefit of victims and communities affected by hate crime. First, ideas for cooperation are often sparked and sustained by CSOs. This can take a lot of energy, patience and maturity as public authorities can be slow to react and move forward on agreed actions. At the same time, cooperation must a two-way street by definition and in Hungary it has engendered effective reactions from public authorities in these examples. The principle of ‘critical friendships’ where CSOs offer honest and frank criticism alongside practical assistance to overcome the problem was an important factor to add meaning and utility to the work described above.[47] However, without institutionalised frameworks for cooperation, supported by leadership and political will, cooperation can end at any time without particular reason or explanation. Indeed there are recent signs that police commitment to cooperation is decreasing. It is an open question how and whether cooperation across police and CSOs might continue in the future.

Strategies for coalition

The WGAHC faces ongoing strategic questions in navigating its relationship with public authorities while aiming to achieve measurable improvements in hate crime recording and victim support in a sensitive political environment.

Another strategic question facing the WGAHC along with other specialist networks on hate crime monitoring is whether its membership should be increased beyond those NGOs that are expert on hate crime recording and data collection and on investigation and prosecution procedure. While this approach would be more inclusive of new and different voices, any lack of experience in the area risks undermining the authority and focus of the group and thus its relationship with the authorities. In turn, the broader question of NGO advocacy strategy was examined by one interviewee, who raised questions about whether it is possible to adopt both a supportive and challenging or even combative approach or whether they are two different functions, best carried out by different NGOs.

National University of Public Service (NUPS)

Since 2012, NUPS has rapidly developed police curricula on hate crime, from initiating the first course on policing hate crime at bachelor’s level to developing masters’ courses and starting a PHD level course in 2017. Enrolment significantly increased, with 10-15 students enrolled in the first year to 50 in the second. NUPS has also achieved success in implementing online learning for police in 2018-2019, securing agreement from the Ministry of Interior for the participation of 550 police officers in its pilot phase, as part of the Facing all the Facts project.

The Faculty of Law Enforcement maintains strong connections with CSOs and the WGAHC in particular and plays a coordinating role in facilitating connections across CSOs and the police. Its regular involvement in international projects brings another positive dimension to its work.[48]

Recommendations and conclusions

This research has highlighted the strengths and weaknesses of Hungary’s hate crime reporting and recording system. The section below lists recommendations synthesised from the workshops, interviews and a strategic analysis of the ‘systems map’.

For public authorities:

Create a strategic framework that brings together key government ministries and agencies to review and improve hate crime recording and data collection mechanisms, including the WGAHC as an equal partner. Consider drawing on the recently adopted protocol developed by Greece, with assistance from the OSCE Office for Democratic and Human Rights.[49]

Within this framework:

- Continue regular meetings to review current and completed cases to identify lessons learned, develop protocols and guidelines for prosecutors that explain the precise evidence needed to prove the ‘hate element’ and incorporate existing guidance on bias indicators, organise joint training on hate crime;

- Develop the recently revised crime recording system to include: victim / witness perception; hate incidents; disaggregation by religion and ethnicity, so that data on anti-Muslim, antisemitic anti-Christian,[50] and crimes against people of African descent or Roma[51] can be extracted;

- Openly communicate information about current efforts including: publishing statistics, and publishing available guidance relating to the investigation and prosecution of hate crime;

- Amend the government’s existing National Crime Prevention Strategy and Action Plan to include a consideration of hate crime.

For the police:

- Build on current training and education programmes, adopt Facing all the Facts online training on hate crime across Hungary.

For the prosecution service

- Set up a prosecutors network, to complement the police hate crime network and incorporate relevant training with input from civil society.

For the National University for Public Service

- Continue to act as a facilitator for coordination between CSOs and the police and other relevant agencies.

For CSOs active in the area of hate crime recording and monitoring

- Reach out and strengthen cooperation across grassroots organisations across all communities and make a specific effort to include organisations supporting victims of disability hate crime. Build their capacity to record and monitor hate crimes and incidents.

Bibliography & Endnotes

Bergold, J, & Thomas, S (2012) ‘Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological

Approach in Motion’ 13(1) Forum: Qualitative Social Research.

Chevalier, J. M., & Buckles, D. J. (2013) Participatory Action Research: Theory and

Methods for Engaged Inquiry. London: Routledge.

EU Fundamental Rights Agency (2013) ‘Racism, discrimination, intolerance and extremism: learning from experiences in Greece and Hungary’, available online at https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2013/racism-discrimination-intolerance-and-extremism-learning-experiences-greece-and, (Accessed on 1 November 2019)

Helsinki Committee et al (2017) Timeline of Government Attacks against Hungarian Civil Society Organisations, Budapest: Helsinki Committee: https://www.helsinki.hu/wp-content/uploads/Timeline_of_gov_attacks_against_ HU_NGOs_short_17112017.pdf

Helsinki Committee (2018) ‘LEXNGO 2018’, https://www.helsinki.hu/en/ lexngo-2018/ (accessed 21 April 2019).

Nagy, L. T. (1994). A szkinhedek és büntetőjogi megítélésük. Esély, 6(1), 53–63.

OSCE Office for Democratic Instititutions and Human Rights (2018a) ’Information Against Hate Crimes Toolkit Programme Description’, Warsaw: ODIHR. https:// www.osce.org/odihr/INFAHCT (accessed 21 April, 2019)

OSCE-ODIHR (2018b) ‚Agreement on Inter-Agency Cooperation on Addressing Racist Crimes in Greece’, available online at https://www.osce.org/odihr/402260, accessed on 1 November 2019.

Perry and Perry-Kessaris (forthcoming) ‘Participatory and designerly strategies for sociolegal research impact: Lessons from research aimed at making hate crime visible’

Perry-Kessaris A (2019) ‘Legal design for practice, activism, policy and research’ 46:2 Journal of Law and Society

Perry, Perry Kessaris (2019) ‘Participatory and designerly strategies for sociolegal research impact: Lessons from research aimed at making hate crime visible’

Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018) Lifecycle of a Hate Crime: Comparative Report. Dublin: ICCL

Working Group Against Hate Crimes in Hungary (GYEM) (2014a) Hate crimes in Hungary. Problems, recommendations, good practices, Budapest: GYEM

Working Group Against Hate Crimes in Hungary (GYEM) (2014b) ‘Law Enforcement Problems in Hate Crime Procedures, the experiences of the Working Group Against Hate Crimes in Hungary’, Budapest: GYEM

Working Group Against Hate Crimes (GYEM) (2015), ‘Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review of Hungary’ http://gyuloletellen.hu/sites/default/files/ gyemupr2016.pdf, Budapest: GYEM

[1] 1 As a general rule, Facing all the Facts uses the internationally acknowledged, OSCE-ODIHR definition of hate crime: ‘a criminal offence committed with a bias motive’.

[2] The following countries were involved in this research: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom (England and Wales).

[3] In terms of its conceptual scope, the research focused on hate crime recording and data collection, and excluded a consideration of hate speech and discrimination. This was because there was a need to focus time and resources on developing the experimental aspects of the methodology such as the workshops and graphics. International and national norms, standards and practice on recording and collecting data on hate speech and discrimination are as detailed and complex as those relating to hate crime. Including these areas within the methodology risked an over-broad research focus that would have been unachievable in the available time.

[4] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a detailed description of the research theory and approach of the project.

[5] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a full description of the research methodology.

[6] See the Methodology section of the European Report for agenda and description of activities.

[19] See Methodology section of the European Report for further detail

[20] Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018), p. 67.

[21] The extent of this ‘disappearing’ varied across national contexts, and is detailed in national reports.

[22] See standards document and self-assessment document

[23] Based on interviews with individual ‘change agents’ from across these perspectives during the research.

[24] For a full description of the main stakeholders included in national assessments, and how the self-assessment framework relates to the ‘systems map’, see the Methodology section of the European Report.

[25] ODIHR Key Observations, http://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/files/documents/Website/Key%20Observations/ KeyObservations-20140417.pdf; this methodology could also be incorporated in the framework of INFAHCT self-assessment, as described on pp. 22-23 here: https://www.osce.org/odihr/INFAHCT?download=true

[26] See Methodology section of the European Report for instructions.

[27] Interviewee one

[28] WGAHC (2015a) paragraph 320.

[29] See Helsinki Committee et al (2017) and Helsinki Committee (2018)

[30] Interviewee three

[31] Interviewee two

[32] Interviewee four

[33] Interviewee four

[34] Interviewee five

[35] This practice was included in FRA’s compendium of practices in 2016, https://fra.europa.eu/en/theme/hate-crime/compendium-practices?countries_eu=418

[36] Interviewee four

[37] Interviewee five

[38] Interviewee four

[39] Interviewee four

[40] See WGAHG (2014a)

[41] Including Facing Fact monitoring guidelines, the IACP guidelines and the ODIHR prosecutors’ guide

[42] The draft was send to 174 individuals/institutions. Feedback was received from 59 organisations/individuals, 36 providing substantive input (for a list of all those who commented see this article summarizing the development of the list).

[43] See http://gyuloletellen.hu/sites/default/files/gyem_indikatorlista_ketoszlopos_vegleges.pdf

[44] http://gyuloletellen.hu/sites/default/files/gyem_indikatorlista_haromolszopos_vegleges.pdf

[45] The three column list has been used widely in CSO-police trainings and at internal trainings for members of the police hate crime network.

[46] UNI-FORM is an initiative of the International Lesbian, Gay, Trans and Intersex Association – Portugal. It allows victims and witnesses to report hate crimes and incidents using the app, which are received by national specialist CSOs. https://uni-form.eu/ about?country=GB&locale=en

[47] This principle is discussed in detail in the European Report.

[48] See for example, https://24.hu/belfold/2019/01/04/gyulolet-buncselekmeny-nke-rendorseg/

[49] OSCE-ODIHR (2018).

[50] Currently all fall under ‘religion’ category

[51] Currently all fall under ‘race’ or ‘ethnicity’ categories

About the authors

Joanna Perry is an independent consultant with many years of experience in working to improve understandings of and responses to hate crime. She has held roles across public authorities, NGOs and international organisations and teaches at Birkbeck College, University of London.

Tamás Dombos is an economist, sociologist and anthropologist, project coordinator and board member at Háttér Society and the Hungarian LGBT Alliance, expert and researcher at the Faculty of Law Enforcement at the National University of Public Service and at the Faculty of Law of Eötvös Lóránd University. His work focuses on homophobic and transphobic hate crimes, and LGBTI rights in general.

Andrea Kozáry is a Professor at the National University of Public Service, Faculty of Law Enforcement in Budapest. She has developed and led courses and trainings in social sciences for many years. She developed the first academic programmes on hate crime for police and has successfully led several European Union projects.

About the designer

Jonathan Brennan is an artist and freelance graphic designer, web developer, videographer and translator. His work can be viewed at www.aptalops.com and www.jonathanbrennanart.com

We would like to thank everyone who took part in our workshops and interviews for their invaluable contribution.

This report has been produced as part of the Facing all the Facts project which is funded by the European Union Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (JUST/2015/RRAC/ AG/TRAI/8997) with a consortium of 3 law enforcement and 6 civil society organisations across 8 countries.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme