Perry, J (2019) Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Greece. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.

Download the full report in PDF here.

Introduction

If we are to understand hate crime,[1] support victims and reduce and prevent the problem, there are some basic questions that need to be answered:

How many hate crimes are taking place? Who are the people most affected? What is the impact? How good is the response from the police? Are cases getting investigated and prosecuted? Are the courts applying hate crime laws? Are victims getting access to safety, justice and the support they need?

While ‘official’ hate crime data, usually provided by police reports, are the most cited source for answers to these questions, they only tell a small part of this complex story. Understanding what happens to cases as they are investigated, prosecuted and sentenced requires a shared approach with cooperation across government agencies and ministries with responsibilities in this area, however, the necessary mechanisms and partnerships are often not in place. Reports and information captured by civil society organisations (CSOs) can provide crucial parts of the jigsaw, yet connection across public authority- civil society ‘divides’ is even more limited.

The Facing all the Facts project used interactive workshop methods, in-depth interviews, graphic design and desk research to understand and assess frameworks and actions that support hate crime reporting, recording and data collection across a ‘system’ of public authorities and CSOs.[2] Researchers adopted a participatory research methodology and worked directly with those at the centre of national efforts to improve hate crime reporting, recording and data collection to explore the hypothesis that stronger relationships lead to better data and information about hate crime and therefore better outcomes for victims and communities.

What was found is that a range of factors are key to progress in this area, including the:

- strength and comprehensiveness of the international normative framework that influences national approaches to reporting, recording and data collection;

- technical capacity to actually record and share information and connect with other parts of the system;

- existence of an underlying and inclusive policy framework at the national level;

- work of individual ‘change agents’ and the degree to which they are politically supported;

- skills and available resources of those civil society organisations that conduct recording, monitoring and advocacy.

The research found that each national context presents a different picture, and none is fully comprehensive or balanced.

This national report aims to describe the context and current picture of hate crime reporting, recording and data collection in Greece and to present practical, achievable recommendations for improvement. It is hoped that national stakeholders can build on its findings to further understand and effectively address the painful and stubborn problem of hate crime in Greece.

It is recommended that this report is read in conjunction with the European report which brings together themes from across the six national contexts, tells the stories of good practice and includes practical recommendations for improvements at the European level. Readers should also refer to the Methodology section of the European Report that sets out how the research was designed and carried out in detail.

How did we carry out this research?

The research stream of the Facing all the Facts project had three research questions:[3]

- What methods work to bring together public authorities (police, prosecutors, government ministries, the judiciary, etc.) and NGOs that work across all victim groups to:

- co-describe the current situation (what data do we have right now? where is hate crime happening? to whom?)

- co-diagnose gaps and issues (where are the gaps? who is least protected? what needs to be done?), and;

- co-prioritise actions for improvement (what are the most important things that need to be done now and in the future?).

- What actions, mechanisms and principles particularly support or undermines public authority and NGO cooperation in hate crime recording and data collection?

- What motivates and supports those at the centre of efforts to improve national systems?

The project combined traditional research methods, such as interviews and desk research, with an innovative combination of methods drawn from participatory research and design research.[4]

The following activities were conducted by the research team:

- Collaborated with relevant colleagues to complete an overview of current hate crime reporting, recording and data collection processes and actions at the national level, based on a pre-prepared template;[5]

- Identified key people from key agencies, ministries and organisations at the national level to take part in a workshop to map gaps and opportunities for improving hate crime reporting, recording and data collection.[6] This took place in Athens on 17 May 2017.

- Conducted in-depth interviews with five people who have been at the heart of efforts to improve reporting, recording and data collection at the national level to gain their insights into our research questions.

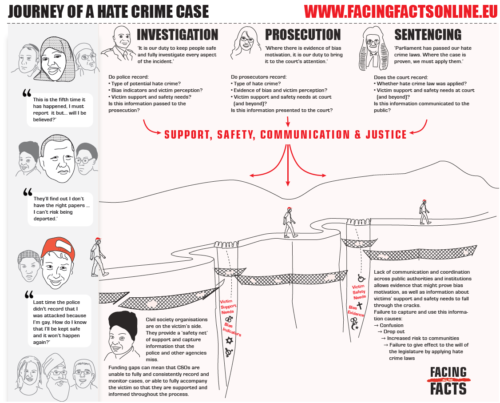

Following the first phase of the research, the lead researcher synthesised existing norms and standards on hate crime to create a self-assessment framework, which was used to develop national systems maps describing how hate crimes are registered, how data is collected and used and an assessment of the strength of individual relationships across the system. A graphic designer worked with researchers to create visual representations of the Journey of a Hate Crime Case (see below) and national Systems Maps (See ‘Mapping the hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’ in Greece’ below).

With a complete draft of the national report and its graphic outputs, a consultation on the findings and recommendations was organised via a second interactive workshop with stakeholders which was held in Athens on 9 October 2018.

During the final phase, the lead researcher continued to seek further input and clarification with individual stakeholders, as needed, when preparing the final report. Overlapping themes from this and other national reports were brought together and critically examined in the final, European Report.

The Greek context

The political, legal, social and technical aspects of hate crime in Greece have been meticulously documented by the Racist Violence Recording Network (the Network) since the second half of 2011. The EU Agency for Fundamental Rights, focused on Greece and Hungary in a recent report and Amnesty International and Human Rights First regularly report on the country. This report will not repeat or rehearse this rich set of information on Greece. It explores the efforts of key actors to implement and improve hate crime recording and data collection processes that are victim-focused and that prioritise collaboration across NGOs and between NGOs and the Greek state. [7]

The journey of a hate crime

Using the workshop methodology described in the Methodology section of the European Report, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[15]

Using the workshop methodology described in the Methodology section of the European Report, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[15]

The Journey graphic conveys the shared knowledge and experience generated from this exercise. From the legal perspective, it confirms the core problem articulated by Schweppe, Haynes and Walters (2018) where, ‘rather than the hate element being communicated forward and impacting the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of the case, it is often “disappeared” or “filtered out” from the process.’[16],[17] It also conveys the complex set of experiences, duties, factors and stakeholders that come into play in efforts to evidence and map the victim experience through key points of reporting, recording and data collection. The police officer, prosecutor, judge and CSO support worker are shown as each being essential to capturing and acting on key information about the victim experience of hate, hostility and bias crime, and their safety and support needs. International norms and standards[18] are the basis for key questions about what information and data is and should be captured.

The reasons why victims do not engage with the police and the criminal justice process are conveyed along with the potential loneliness and confusion of those who do. The professional perspective and attitude of criminal justice professionals that are necessary for a successful journey are presented.[19] NGOs are shown as an essential, if fragile, ‘safety net’, which is a source of information and support to victims across the system, and plays a role in bringing evidence of bias motivation to the attention of the police and the prosecution service.

The Journey communicates the normative idea that hate crime recording and data collection starts with a victim reporting an incident, and should be followed by a case progressing through the set stages of investigation, prosecution and sentencing, determined by a national criminal justice process, during which crucial data about bias, safety and security should be captured, used and published by key stakeholders. The graphic also illustrates the reality that victims do not want to report, key information about bias indicators and evidence and victims’ safety and support needs is missed or falls through the cracks created by technical limitations, and institutional boundaries and incompatibilities. It is also clear that CSOs play a central yet under-valued and under-resourced role.

As with most contexts, there is serious under-reporting of hate crimes to the police and to NGOs in Greece. There are also gaps in provision, support and information for victims, leading to drop out and poor outcomes. These points are addressed in more detail when we look at Greece’s ‘system’ of hate crime recording and data collection below.

Click here to download the Journey in Greek.

Mapping the hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’ in Greece

The ‘linear’ criminal justice process presented in the Journey graphic is shaped by a broader system of connections and relationships. Extensive work and continuous consultation produced a victim-focused framework and methodology, based on an explicit list of international norms and standards that seeks to support an inclusive and victim-focused assessment of the national situation, based on a concept of relationships. It integrates a consideration of evidence of CSO-public authority cooperation on hate crime recording and data collection as well as evidence relating to the quality of CSO efforts to directly record and monitor hate crimes against the communities they support and represent.[20] In this way it aims to go beyond, yet complement existing approaches such as OSCE-ODIHR’s Key Observations framework and its INFAHCT Programme.[21] The systems map also serves as a tool to support all stakeholders in a workshop or other interactive setting to co-describe current hate crime recording and data collection systems; co-diagnose its strengths and weaknesses and co-prioritise actions for improvement.[22]

The interactive ‘Systems map’ below is best viewed in full screen mode (click on the icon in the top right hand corner of the map).

Click on the ‘+’ icons for an evidence-based explanation of the colour-coded relationship, based on international norms and standards.

Or download ‘Self-assessment grid on hate crime recording and data collection, framed by international norms and standards – GREECE (PDF 306 KB)‘

Overview and Commentary

The quality of connections and relationships across Greece’s hate crime reporting and recording system is mixed. The Racist Violence Recording Network has been the central ‘engine’ for efforts to make hate crime visible. It has the strongest connections across groups affected by hate crime as well as to those government ministries and agencies with strategic and operational responsibilities in this area. However, in the absence of an implemented strategic framework, the connections across the system between the police and victims, the prosecution service and relevant government ministries are relatively weak. Recent developments on the establishment of a strategic inter-agency working group, and planned trainings for the prosecution and judicial authorities are encouraging and show significant promise for a step-change in national frameworks and action.[23] The recommendations section below suggests how to support these potentially significant achievements.

The map illustrates the tendency for public authorities to share data and information about hate crime with third parties at the international level (e.g. The European Commission, the European Agency for Fundamental Rights and The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights) as opposed to proactively and independently publishing and disseminating data and information to the Greek public.

As in other countries, people experiencing anti- Roma and anti- disability hate crime are particularly under-served by all those involved in hate crime monitoring and data collection.

National historical context

The next sections give context to the ‘systems map’ and ‘journey of a hate crime case’. They present themes gathered through the ‘connecting on hate crime data’ workshops, desk research and interviews with change agents at the centre of efforts to progress Greece’s work on understanding and addressing hate crime.

One interviewee pointed to the fact that in Greece, as in several countries, hate crime was ‘assimilated in society’ before the escalation in violence in 2011 made the problem impossible to ignore.[24] Civil society and public authorities responded to the situation, from different starting points. On the one hand, the Network conceptualised the escalation in violence as a human rights issue of refugee and victim protection, from both organised and ‘ordinary’ perpetrators. On the other, the pattern of responses by the police and Greek institutions suggests that the problem was perceived as one of public order and almost entirely related to the actions of extremist groups. The complementarity and conflict in these approaches might partly explain later (in)action at the national level to take a victim-focused approach to recording and responding to hate crime in Greece.

While the country faces many challenges in the area of hate crime recording and responses, one interviewee captured the general feeling among those at the centre of these efforts: ‘There has been progress; we are not at step one’.[25] The setting up of the RVRN and an increased quality of police-CSO cooperation in monitoring and responding to hate crime described in this report are some examples of the progress achieved.

However, even this limited progress has been uneven and in one interviewee’s words, ‘a constant challenge’. As illustrated in the systems map above, the Network is the engine forming connections across responsible actors and sectors. Until very recently, the enduring challenge had been to secure the basis of a systematic and strategic approach to the problem that spans all responsible actors across public institutions and is underpinned by political leadership. In June 2018, a landmark Agreement on inter-agency co-operation on addressing racist crimes in Greece was signed by all relevant ministries and a working group was established including representation from the Racist Violence Recording Network.

Police-Civil Society connection on hate crime recording and monitoring: a process of cooperation

While police and NGO interviewees and workshop participants acknowledged that police and NGOs hold ‘negative stereotypes on both sides’ that can present barriers to cooperation, it is clear that the Network as a whole and its individual members have built positive relationships with the police at the working level. As explained by one interviewee,

‘Building relationships is a challenge and it is very rewarding when this happens because many things can be solved especially at the working level. It is very important for the police to know what [are] the nearest NGOs that can support a case and to be able to call them saying, ‘look I need some help and can you help in this incident’. The police get help and they show that they are doing the work. It’s a win-win situation basically’.[26]

The same interviewee made the connected point: ‘Some police have expressed their concern about why all of the network incidents don’t go to the police. This shows an interest. An interest because they want to show that they want to do their work.’

Another interviewee pointed to the practical, ‘on the ground’ actions that contribute to institutionalising positive relationships: ‘You don’t want to [only] knock on open doors. You need to find closed doors and to do that you need to make the practical argument: I am here to make our lives easier’.[27] The same interviewee pointed to the importance of taking up the challenge of training police who really need it and are not ‘on our side’.

One interviewee pointed to the energy that CSOs often need to invest in these relationships, while drawing on limited resources ‘[sometimes we] have to prove that we are reliable, and this takes energy’.[28] Another interviewee pointed to the tension inherent in recording hate crimes that are perpetrated by the police, ‘keeping them in the spotlight as perpetrators but at the same time … also trying to cooperate with them’.[29]

It was generally agreed that the establishment of the specialist racist hate crime unit within the police was a very positive move that allows a ‘concrete’ contact point within the police and represented the first effort by the state to provide an effective institutionalised response to hate crime.[30] One interviewee reflected that at its inception, the unit was ‘weak’ and staffed by people who ‘didn’t want to be there’, however its expertise and commitment has grown as the problem and need for action has become clearer, in no small part as a result of efforts of the Network.[31]

The police lead on hate crime data reflected that the current network of specialist police units could be strengthened through regular meetings,

‘What would be needed is that all of us (the 70 services and HQ) dealing with racist crime meet inside the police once a year to exchange views, to assess what we do. Communication becomes difficult as policemen have other issues to deal with as well.’[32]

The bigger picture: connecting the ‘bubbles’

One interviewee painted a vivid picture of the current strategic situation in Greece,

‘At the moment, within the Greek administration there are people, or individuals, bubbles of people, bubbles of knowledge, but sometimes these are not linked or even if they are linked at the working level, for some of these issues to actually progress you need also the higher level. There is enormous work that can be done from the bottom up, but not everything. For more sophisticated systems of coordination to be set up then you need the political will at the higher level. Otherwise you just have people exchanging emails and excel sheets when you need a database to connect data recorded by civil society, police, judiciary; and you need an authority to produce comparative analysis of this data. There are things that can be done in terms of the human aspect. We can promote further communication and coordination and the network has played a crucial role in liaising [with] all these bubbles, but we cannot do everything.’[33]

Overall, interviewees acknowledged that Greece and Athens in particular has developed in-depth expertise on hate crime, including CSO staff, many police officers and several public officials in other agencies and institutions. Applying the ‘bubbles’ concept to this situation, it is clear that without connection and support, there is the potential for these individuals to become overwhelmed with the scale and complexity of the challenges that they face. Interviewee five pointed out that it is important to support experts, wherever they are based, to transfer knowledge to others and for them to receive some recognition for their work. Ideas on the nature of this potential support are explored in the recommendations below and the European report.

Other interviewees echoed interviewee three’s observation above, ‘Where is [official data], who is doing it, where is it kept, who is making the analysis…when are we to find data regarding how many hate crimes were recognised, reports, court, convictions, follow up? It’s darkness’. The same interviewee pointed to the need for a central mechanism, ‘to monitor all this valuable data that gets lost’.[34]

There is a potential to deepen connections across the Network and police in the first instance to build a more complete picture of the nature and prevalence of hate crime in Greece, its effect on victims and what helps to support them. Police and members of the network could benefit from coming together to share hate crime recording methods, including categories and ‘evidential’ requirements and identify possible points of connection between and among data sources. Where possible, elements of data can be brought together to paint a more informative picture, while protecting victim confidentiality and the independence of all sides.

At the political level, the situation is more challenging. One interviewee powerfully explained how a lack of political will, ‘for the most basic things’ can seriously undermine the confidence of everyone working in this field. Citing the fact that it took a year to find a courtroom to deal with the Golden Dawn trial, she pointed out that this gives the wrong message to the judge, ‘When they see that we have the biggest trial of the millennium and see that the state is looking at it as any other trial, then what is the message that [the judges] get?’.[35] There is potential for the recently established working group overseeing the implementation of the interagency protocol to provide the framework, focus and resources that are needed to progress on the issues identified here.

The Racist Violence Recording Network in Focus

The Racist Violence Recording Network has revealed the nature of contemporary targeted violence in Greece. The victim’s experience was made undeniable through the Network’s robust methodology, and made legitimate through the strategic and institutional backing of powerful coordinating partners. It connected diverse stakeholders at the local, national and international levels to evidence the problem of hate crime and the quality of and gaps in responses to it. As such it deserves particular examination and focus.

The Network’s recording methodology

The Network’s members are united by a transparent methodology, which is based on direct testimony from victims. In this sense, members are ‘on the same page’ when recording incidents, while also being free to fulfil their own diverse missions to meet the medical, legal, housing and even nutritional needs of their users.

The Network is the ‘link between the grass roots and the state’. As one interviewee pointed out, ‘at some point these “poles” had to start talking to each other.[36] As time progressed, the Network was recognised by public authorities, IGOs, the media and politicians alike as the main source of information for racist, homophobic and transphobic attacks in Greece. Institutional backing from UNHCR and the National Commission for Human Rights was essential to secure the legitimacy of its data.[37]

Further, conceptualising racist violence in Greece as an issue of refugee protection allowed UNHCR to take a leading role and to commit resources to a service that didn’t discriminate on the grounds of migration or legal status.

The network’s story[38]

The network was created during a terrible time yet with a strong and unifying sense of urgency and the benefit of particularly inspirational change agents in the form of the Head of the Greek Commission for Human Rights and the Head of UNHCR Greece.

Daphne Kapatenaki from UNHCR, Greece was involved in the early work to set up the Racist Violence Recording Network,

‘…initially we thought it was a pilot, just to see what was happening, but then we realised that there was huge gap. We were learning ourselves. We realised that the country didn’t have national data, that the country was reporting to international organisations that there were only 1 to 2 incidents [recorded] per year. We realised there were gaps in various administrations. We realised that there was a real need from the ground. The Network’s added value is that it is the only opportunity for the victims’ voice to be heard even at the higher level. So the voices of the victim are recorded by grassroots organisations that come into contact with these orgs. This is reflected in their annual report. The trends and the different qualitative nature of the attacks is registered. It is used by all kinds of institutions, national institutions and at the EU level to highlight the phenomenon of racist violence in Greece….The response of the authorities was disproportionately poor relating to what is happening and even recorded by journalists. We spent a couple of years where crimes were coming to the surface by the NGOs, but still delayed response by the competent authorities.’

Recalling the beginnings of the Network, Daphne interviewee identified the murder of Kantaris on 10 May 2011, as prompting and unravelling the cycle of violence in Athens.[39]

‘It moved and shocked us and made us realise that we need to do something. Even if recording is the only thing that we can do, let’s do that. Back then we didn’t feel that recording was going to change the whole narrative. Because when you are faced with such enormous issues, all this violence, you feel that okay I am going to record and then what? Which is exactly what victims feel, by the way. Sometimes they don’t have the energy to report, because they feel that they won’t get justice so what’s the point.”

Here the ‘drop in the ocean’ of recording incidents, is set against the accepted imperative to do what one can to make the problem visible.

Another interviewee explained the importance of ‘being ready’ with information when there is a political shift towards listening to the Network’s advocacy,

‘The network realised that when the climate for the discussion was more open, then the network provided this valid and serious dressing of the data. Because you have on the one hand parts of the state that don’t want to hear (some want to hear, some don’t want to hear), and then you also have groups of people who are in solidarity. When the state says, okay I have had enough of your nagging, show me your data, then you provide data that nobody can say okay this is an exaggeration, okay this never happened… You present data in a way that they cannot ignore it. You don’t want to substitute what is happening in grassroots. You want to make the link between the grassroots and the state. If you want civic and institutional change, then at some point these two ‘poles’ have to talk to each other and the network [is] the intermediator between them….’I think that the network was very good at catching this momentum’.

It is probably most accurate to say that the Network was ready to influence and ‘catch the momentum’ when political awareness of the problem changed and when political leaders and law enforcement agencies needed to be seen to be doing something. This research found that the influence of the network’s evidence is visible in the decision to set up specific police units, the revision of national hate crime laws and informing the court during the sentencing of Shehzad Luqman’s murder as a hate crime. One interviewee recalled drawing on the expertise of the Network’s members to provide expert input into the Luqman case: ‘It just felt so rewarding, all this work was not without purpose. Suddenly the work of the network went to another level.’[40]

The Network’s influence can also be evidenced by the significant increase in the number of hate crimes registered by the State. For example, in 2012 one hate crime was reported by the Greek authorities to ODIHR for inclusion in their annual hate crime report. In 2013, the number jumped to 109 hate crimes (the Network published its first full report at the end of 2012). One interviewee emphasized the broader context, ‘You cannot say that it was the network that changed everything. Because if it is so easy, you wouldn’t need a network, because at the same time, shouldn’t be pessimistic, because it is all things together that led to the change, not one thing or the other thing’.[41]

The impact of the network was acknowledged by a police representative:

‘The Network has helped in highlighting the need for recording and improving systems for the recording of data concerning racist crimes, it has highlighted problems in police training, and it has contributed in raising awareness among policemen so that they can be more specifically trained in racist crimes. Of course, given that it operates as a “monitoring-observatory” it does create some negative bias, but when criticism is well-meant, it helps us set our shortcomings straight. The overall impression of the police (and its leadership) is that the Network’s efforts are in the same direction as ours, in better addressing racist crime through services that support the victims, through training, through cooperation with institutions (the National Council against Racism and Intolerance). The police is not detached from society, therefore the Network as a part of society is our interlocutor.’

The journey from almost complete invisibility of hate crime as a social problem in Greece to an acceptance of the Network’s central role as a documenter of this violence and a key ally of the police has been long but powerful. There is an opportunity for the Network and public authorities to further consolidate and build on their current relationships for more systematic input into training and information sharing about the changing problem of hate crime in the country.

There are some specific challenges facing the network during this time of constant change in Greece, which are highlighted in the systems map and will be addressed further in the recommendations. In brief they are as follows:

- the focus on in-person recording on violent incidents might increase the chance that ‘low level’ incidents are missed. It is also more difficult to capture incidents against victims in transit, who are less inclined to report in-person to network members;

- the constant strain on resources means that NGOs have to choose to provide basic services such as ensuring food and shelter and referrals to health services, instead of investing the time it takes to record hate incidents; and

- the spread of hate incidents to Greece’s many islands presents challenges for Network members in terms of training and their capacity to record and monitoring hate crimes and provide support to victims.

A pervasive theme affecting all organisations, agencies and institutions with responsibilities to monitor and respond to hate crime is the dearth of resources:

‘So we all know that when you are working without a dedicated project, this work is done on top of their activities. Very few managed to get dedicated funds to run projects responding to hate crimes. When you don’t have these dedicated projects and you have an emergency, it goes without saying that the NGOs will focus on the basic needs of the refugees. So we believe that there were incidents that were not recorded by NGOs in this context.’[42]

The impact of the refugee crisis/ emergency

On 18 March 2016, the EU-Turkey statement agreeing that all new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey into Greek islands as from 20 March 2016 to be returned to Turkey adds another dimension:

‘there are more people staying on the Greek islands for longer periods of time. So together with the EU-Turkey statement, there are also national procedures by the asylum services about this is to be implemented. It means having asylum seekers for lengthy periods, people feeling stranded in the islands, reception conditions are exhausted or not appropriate and this has created fruitful ground for another type of racist sentiment to develop, to evolve and to continue as we speak. It is a very worrying phenomenon. It has all the elements causing alarm to us, we are very closely monitoring the situation at the moment on the islands. There were very violent incidents in the islands, for example in Leros. It is also linked to national policies dealing with asylum and migration so that’s a new context that we need to take into consideration and adapt our work.’[43]

Recommendations

Following the adoption of the Agreement on inter-agency co-operation on addressing racist crimes in Greece, there is an opportunity to build on the significant progress achieved on hate crime reporting and recording outlined in this report. The recommendations below suggest concrete steps that can be taken by all stakeholders.

Recommendation 1: Agree and establish continuous channels of communication between the Hellenic Police and the Network. The interagency protocol only commits the Greek authorities to ‘compare’ its data with those of the Network. Bearing in mind the high quality of the Network’s data, there is an opportunity for deeper and more effective cooperation. Actions to consider include:

- Set up a process for data sharing with victim confidentiality and protection at its heart. A first step could be to arrange a workshop during which RVRN members, police officers and statisticians share the detail of their hate crime recording processes and identify connection points – that allow for comparing incidents, taking into account the necessary steps to protect victim confidentiality and the professional and organisational independence of all involved.[44]

- Agree a memorandum of understanding on regular cooperation on training, including through the OSCE-ODIHR TAHCLE and PAHCT programmes.

- Introduce twice-yearly meetings of all 70 specialist police units to strengthen cooperation and connection across the country

Recommendation 2: Secure a victim focus in the work of the National Council against Racism and Intolerance and the recently established working group on hate crime. For example, a sub-group could consider what steps each member of the group can take to ensure that obligations under the Victims’ Directive are fully discharged and to take steps to design and carry out a national victimisation survey, which would add to the national knowledge on the prevalence of hate crime in Greece.

Recommendation 3: Support dangerously stretched and exhausted support NGOs to continue recording and monitoring along with their other duties.

Recognise that current priorities are to support the activities of those NGOs that can evidence effective monitoring and victim support. Consider supporting work that explores how to better meet the needs of people targeted by disability hate crime and by anti-Roma hate crime.

Recommendation 4: UNHCR offices in other countries that have seen an increase in racist crime threatening the protection of refugees and hindering efforts for integration of refugees should consider a stronger role in supporting coalitions to monitor and address hate crimes. In so doing, they should draw on the significant expertise and knowledge of UNHCR, Greece.

Recommendation 5: In order to broaden the reach and effectiveness of the Network, it should consider:

- augmenting its current recording model to include online reporting, allowing for ‘low level’ incidents to be recorded in several languages;

- identifying actions that improve training and support in islands where there has been an increase in racist violence.

Recommendation 6: Government ministries, agencies and institutions should take steps to publish all available hate crime data and make it easily accessible to the general public.

Bibliography & Endnotes

Amnesty International (2018) ‘Greece 2017/2018’, available at https://www. amnesty.org/en/countries/europe-and-central-asia/greece/report-greece/ (accessed on 23 April, 2019)

Council of the European Union (2016) ‘EU-Turkey Statement, 18 March 2016’, available at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/(accessed on 23 April, 2019).

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2013) ‘Racism, discrimination, intolerance and extremism: learning from experiences in Greece and Hungary’, available at https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2013/racism-discrimination-intolerance-and-extremism-learning-experiences-greece-and, (accessed on 23 April, 2019)

Human Rights Watch (2012) ‘Hate on the Streets’. Available at https://www.hrw. org/report/2012/07/10/hate-streets/xenophobic-violence-greece (accessed on 23 April, 2019)

The Organisation for Cooperation and Security in Europe (2018) ‘Agreement on inter-agency cooperation on addressing racist violence in Greece’. Available at https://www.osce.org/odihr/402260?download=true, (accessed on 23 April, 2019)

Racist Violence Recording Network (2014) ‘Annual Report, 2012’, Available at, http://rvrn.org/category/reports/page/8/ (accessed 22 April, 2019)

Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018), Lifecycle of a Hate Crime: Comparative

Report. Dublin: ICCL p. 67

[1] As a general rule, Facing all the Facts uses the internationally acknowledged, OSCE-ODIHR definition of hate crime: ‘a criminal offence committed with a bias motive’

[2] The following countries were involved in this research: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom (England and Wales).

[3] In terms of its conceptual scope, the research focused on hate crime recording and data collection, and excluded a consideration of hate speech and discrimination. This was because there was a need to focus time and resources on developing the experimental aspects of the methodology such as the workshops and graphics. International and national norms, standards and practice on recording and collecting data on hate speech and discrimination are as detailed and complex as those relating to hate crime. Including these areas within the methodology risked an over-broad research focus that would have been unachievable in the available time.

[4] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a detailed description of the research theory and approach of the project.

[5] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a full description of the research methodology.

[6] See the Methodology section of the European Report for agenda and description of activities.

[7] This timeline includes: hate crimes that reached the national consciousness often because of the public visibility of its impact on the family and communities or because of a poor response to the incident by the authorities; key developments on improving hate crime recording and data collection such as the publication of an important report, national hate crime strategy or action plan, the setting up of a relevant institution, or the first meeting of national group set up to actively address the issues.

[15] See Methodology section of the European Report for further detail

[16] Schweppe et al (2018) p. 67.

[17] The extent of this ‘disappearing’ varied across national contexts, and is detailed in national reports.

[18] See Standards Document

[19] Based on interviews with individual ‘change agents’ from across these perspectives during the research.

[20] For a full description of the main stakeholders included in national assessments, and how the self-assessment framework relates to the ‘systems map’, see the Methodology section of the European Report.

[21] ODIHR Key Observations, http://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/files/documents/Website/Key%20Observations/ KeyObservations-20140417.pdf; this methodology could also be incorporated in the framework of INFAHCT self-assessment, as described on pp. 22-23 here: https://www.osce.org/odihr/INFAHCT?download=true

[22] See Methodology section of the European Report for instructions.

[23] See above timeline and systems map

[24] Interviewee two

[25] Interviewee one

[26] Interviewee three

[27] Interviewee two

[28] Interviewee one

[29] Interviewee two

[30] Interviewee five

[31] Interviewee two

[32] Interviewee four

[33] Interviewee three

[34] Interviewee one

[35] Interviewee two

[36] Interviewee two

[37] As interviewee one pointed out, ‘We all know that data coming from grassroots orgs is very often challenged by public agencies. Sometimes for valid reasons, because of the lack of reliable methodology of some NGOs.’

[38] This case study has also been included in the Facing Facts Online Decision Makers course. See facingfactsonline.eu for more.

[39] Interviewee three

[40] Interviewee three

[41] Interviewee two

[42] Interviewee three

[43] Interviewee three

[44] For further details on how to set up information-sharing protocols, see the main European report.

About the author

Joanna Perry is an independent consultant, with many years of experience in working to improve understandings of and responses to hate crime. She has held roles across public authorities, NGOs and international organisations and teaches at Birkbeck College, University of London.

About the designer

Jonathan Brennan is an artist and freelance graphic designer, web developer, videographer, artist and translator. His work can be viewed at www.aptalops.com and www.jonathanbrennanart.com

Many thanks to Dina Vardaramatou and her team for organising the national workshops and interviews. We would like to thank everyone who took part in our workshops and interviews for their invaluable contribution. Special thanks to Tina Stavrinaki, Coordinator of the Racist Violence Recording Network who was untiring in giving her warm support and help as we drew on her deep expertise and knowledge throughout the project.

This report has been produced as part of the ‘Facing all the Facts’ project which is funded by the European Union Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (JUST/2015/RRAC/ AG/TRAI/8997) with a consortium of 3 law enforcement and 6 civil society organisations across 8 countries.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme