Perry, J (2019) Connecting on Hate Crime Data in England and Wales. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.

Download the full report in PDF here.

Introduction

In 2016, the referendum on the United Kingdom’s membership of the European Union was followed by a disturbing spike in hate crimes and a sharp increase in public awareness about the existence and impact of the problem. Alongside the many examples of public action and solidarity against hate crime there is also evidence of skepticism and confusion about its impact as a social problem and its worth as a policy priority. ‘Austerity’ continues to threaten irreparable damage to the policy and practice that has been painstakingly established over the years.

The legal, policy, practice and research landscape of hate crime in England and Wales is rich, complex, well documented and under constant review and scrutiny. This report doesn’t attempt to deal with every aspect of hate crime in England and Wales, or to replicate high quality previous or ongoing research.[1] The Facing all the Facts project took a participatory approach to explore the actual and potential hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’ and to co-design ways to make it visible to its diverse stakeholders. Interviews with key people at the centre of efforts to understand and address hate crime helped identify key challenges and possible actions for improvement in hate crime reporting and recording at the national level.[2] Our starting point has been that if essential – and sometimes basic – questions about the prevalence and impact of hate crime are to be answered, then effective frameworks, systems and principles for cooperation across diverse actors must be implemented and used. No single agency or organisation has the full picture. The less understood, yet vital, interface between public authorities and civil society organisations, and what supports, and what undermines effective cooperation, was a particular focus of this research.

More specifically, the research in England and Wales evolved to explore two areas:

- to get under the skin of impressive practice in the area of public authority-civil society cooperation (CSO) on hate crime reporting and recording, and to identify the key success factors from the perspective of those at the centre of this work with the aim of sharing the lessons learner with a broader European audience;

- to critically examine the current strengths and weaknesses of ‘Third-Party Reporting’ processes with the aim of making constructive recommendations at the national level.

The outputs of the first area are included as case studies in online learning for decision makers and as themes in the European Report. The second area of examination is presented in Part III of this report, and its potential international application is discussed in the European Report.

Recommendations relating to third-party reporting focus on:

- defining and securing a strategic focus on the purpose and function of ‘Third-Party Reporting’ processes and structures;

- using the breadth of data that is already available to public authorities to make more informed decisions on addressing hate crime, and racist crime in particular;

- building on successful practice;

- doing better at addressing under-served communities.

Guide to this report

Part I gives an overview, or timeline, of the key events that shaped national understanding of hate crime and the technical decisions and actions that improved hate crime recording and data collection.

Part II shares two graphics developed during workshops in 6 countries to depict the victim perspective as a crime progresses through the criminal justice system and to describe the institutions and organisations that record and collect hate crime data as a ‘system’ requiring a victim focus and strong relationships to build a comprehensive picture of hate crime and effective responses to it. The strengths and weaknesses of the England and Wales’ hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’ are presented and analysed.

Part III focuses on current issues relating to third party reporting, drawing on interviews with experts, research findings and the recent report Understanding the Difference, by Her Majesty’s Inspection of Constabulary and Fire and Rescue Services (HMICFRS) to propose recommendations in Part V.

Part IV looks at the data that is already available and how it might be better used to improve responses, with a particular focus on racist hate crime.

Part V presents the report’s recommendations.

How did we carry out this research?

The research stream of the Facing all the Facts project had three research questions:[3]

- What methods work to bring together public authorities (police, prosecutors, government ministries, the judiciary, etc.) and NGOs that work across all victim groups to:

- co-describe the current situation (what data do we have right now? where is hate crime happening? to whom?)

- co-diagnose gaps and issues (where are the gaps? who is least protected? what needs to be done?), and;

- co-prioritise actions for improvement (what are the most important things that need to be done now and in the future?).

- What actions, mechanisms and principles particularly support or undermines public authority and NGO cooperation in hate crime recording and data collection?

- What motivates and supports those at the centre of efforts to improve national systems?

The project combined traditional research methods, such as interviews and desk research, with an innovative combination of methods drawn from participatory research and design research.[4]

The following activities were conducted by the research team:

- Collaborated with relevant colleagues to complete an overview of current hate crime reporting, recording and data collection processes and actions at the national level, based on a pre-prepared template;[5]

- Identified key people from key agencies, ministries and organisations at the national level to take part in a workshop to map gaps and opportunities for improving hate crime reporting, recording and data collection.[6] This took place in Leeds on 28 November 2017.

- Conducted in-depth interviews with seven people who have been at the heart of efforts to improve reporting, recording and data collection at the national level to gain their insights into our research questions.

Following the first phase of the research, the lead researcher synthesised existing norms and standards on hate crime to create a self-assessment framework, which was used to develop national systems maps describing how hate crimes are registered, how data is collected and used and an assessment of the strength of individual relationships across the system. A graphic designer worked with researchers to create visual representations of the Journey of a Hate Crime Case [see section x] and national Systems Maps [see section X]. Instead of using resources to launch the national report, it was decided that more connection and momentum would be generated at the national level, and a more accurate and meaningful final report would be produced, by directly consulting on the findings and recommendations during a second interactive workshop which was held in London on 7 November 2018.

During the final phase, the lead researcher continued to seek further input and clarification with individual stakeholders, as needed, when preparing the final report. Overlapping themes from this and other national reports were brought together and critically examined in the final, European Report.

Part I: the National Context

This section presents a timeline of key events that: shaped national understandings of hate crime; or introduced important tools and frameworks to improve the monitoring and recording of hate crime.[7]

In uncovering the disastrous response to Stephen Lawrence’s murder, the Macpherson Inquiry ignited what turned out to be a sustained commitment to address hate crime across successive governments, and an institutional shift in the police and the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) approach towards victims and communities.[12] A suite of legislation was passed; a shared definition of hate crime was agreed across the police, CPS and other criminal justice agencies; hate crime questions were added to the Crime Survey for England and Wales; a system of recording and data collection guidelines and regular reporting on hate crime across the police and criminal justice agencies was established; and information sharing protocols were agreed with the key national Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) that record hate crime and support victims.

The perception-based definition of a ‘racist incident’, recommended by the Inquiry and adopted and expanded by government, generated the backbone of the UK’s current hate crime recording policy. Power to name hate incidents and crimes was shifted towards victims and communities and public authorities were now required to take their perception into account at the investigation and prosecution stages.[13] A space was created for meaningful institutional connection between public authorities tasked with protecting communities targeted by hate crime and CSOs that are committed to supporting victims and making visible the violence that their communities live with every day.

Developments in the area of law, policy, research,[14] activism[15] and practice continue. The Law Commission’s review of the current legal framework for hate crime sets out its strengths and weaknesses alongside recommendations for consideration by the government.[16],[17] The Government published its updated Hate Crime Action plan, including commitments on victim support, prevention and hate crime recording and data collection.

The UK has one of the most comprehensive hate crime reporting, recording and data collection systems in the world. As we will see in the systems map below, the quality and quantity of hate crime data it produces, including by public authority-CSO partnerships has also steadily improved over the years.

However, there are still questions about how existing data is actually used to understand and meet community needs for hate crime to stop, for support, for protection and for justice. There are particular gaps and weaknesses in the country’s hate crime reporting and recording ‘system’ in the areas of racist crime and disability hate crime. The next section analyses the current system of relationships that produce and respond to data in relation to the prevalence and impact of hate crime, followed by further analysis and recommendations.

Part II: The ‘journey’ of a hate crime and the ‘system’ of hate crime recording and data collection in England and Wales

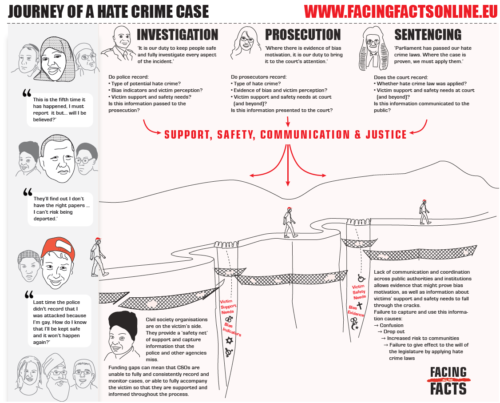

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[18]

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[18]

The Journey graphic conveys the shared knowledge and experience generated from this exercise. From the legal perspective, it confirms the core problem articulated by Schweppe, Haynes and Walters where, ‘rather than the hate element being communicated forward and impacting the investigation, prosecution and sen-tencing of the case, it is often “disappeared” or “filtered out” from the process.’[19] It also conveys the complex set of experiences, duties, factors and stakeholders that come into play in efforts to evidence and map the victim experience through key points of reporting, recording and data collection. The police officer, prosecutor, judge and CSO support worker are shown as each being essential to capturing and acting on key information about the victim experience of hate, hostility and bias crime, and their safety and support needs. International norms and standards[20] are the basis for key questions about what information and data is and should be captured.

The reasons why victims do not engage with the police and the criminal justice process are conveyed along with the potential loneliness and confusion of those who do. The professional perspective and attitude of criminal justice professionals that are necessary for a successful journey are presented.[21] NGOs are shown as an essential, if fragile, ‘safety net’, which is a source of information and support to victims across the system, and plays a role in bringing evidence of bias motivation to the attention of the police and the prosecution service.

The Journey communicates the normative idea – that hate crime recording and data collection starts with a victim reporting an incident, and should be followed by a case progressing through the set stages of investigation, prosecution and sentencing, determined by a national criminal justice process, during which crucial data about bias, safety and security should be captured, used and published by key stakeholders. The graphic also illustrates the reality that many victims do not want to report, key information about bias indicators and evidence and victims’ safety and support needs is missed or falls through the cracks created by technical limitations, and institutional boundaries and incompatibilities. It is also clear that CSOs play a central yet under-valued and under-resourced role.

The ‘system’ of hate crime recording and data collection in England and Wales

The ‘linear’ criminal justice process presented in the Journey graphic is shaped by a broader system of connections and relationships that needs to be taken into account. Extensive work and continuous consultation produced a victim-focused framework and methodology, based on an explicit list of international norms and standards that seeks to support an inclusive and victim-focused assessment of the national situation, based on a concept of relationships. It integrates a consideration of evidence of CSO-public authority cooperation on hate crime recording and data collection as well as evidence relating to the quality of CSO efforts to directly record and monitor hate crimes against the communities they support and represent.[22] It aims to go beyond, yet complement existing approaches such as OSCE-ODIHR’s Key Observations framework and its INFAHCT Programme.[23] The systems map also serves as a tool to support all stakeholders in a workshop or other interactive setting to co-describe current hate crime recording and data collection systems; co-diagnose its strengths and weaknesses and co-prioritise actions for improvement.[24]

The interactive ‘Systems map’ below is best viewed in full screen mode (click on the icon in the top right hand corner of the map).

Click on the ‘+’ icons for an evidence-based explanation of the colour-coded relationship, based on international norms and standards.

Or download ‘Self-assessment grid on hate crime recording and data collection, framed by international norms and standards – England & Wales (PDF 387KB)‘

Commentary

This assessment is based on international norms and standards, which England and Wales generally exceeds. However, it is important to note that this doesn’t mean that there isn’t significant room for improvement.

Overall, policy frameworks are robust, allowing comprehensive and detailed data to be captured and shared across the system, however technical improvements are needed. For example, currently, hate crime flags are manually ‘passed’ from police to prosecution and throughout the Criminal Justice System, and the CPS alone gathers information from several, unlinked databases, allowing room for human error. There are plans to integrate the case and data management systems of criminal justice agencies, however timescales are unclear.

Information-sharing agreements between CSOs and the police at the national level are unique in Europe and beyond, allowing intelligence-sharing and risk reduction, providing an institutional basis for strong partnerships. However, there are no national CSO counter parts for disability hate crime and racist crime. This is a major gap. There also isn’t full national coverage for anti-LGBT+ hate crime reporting, recording and support.

While Stop Hate UK has a national presence in terms of relationships with government agencies, information sharing agreements, and other charities/NGOs, the organisation can only provide telephone support services in the areas where funding has been secured. There is scope for better coordination and partnerships working between Stop Hate UK and specialist organisations as they provide services such as a 24 hour helpline that smaller organisations cannot sustain with limited resources.

There is a lack of data and information on how victims are using CSO services, suggesting the need for evaluation in this area.

There was a theme across the interviews that the benefit of signing common information-sharing agreements with the police identified above, such as better referrals across NGOs, has contributed to the development of what one interviewee called an ‘anti-hate crime community’.

‘The amount of network across groups and strands has increased …even 5 years ago you simply did not have networks of NGOs from Muslim, Jewish, LGBT, and disability in informal networks, never mind actual formal practical partnerships . Now you really have that and it’s growing. You have an anti-hate crime community that encompasses all these different NGOs, civil servants, police officers, lots of interested parties….Things like Hate Crime

Awareness Week and No to Hate Awards really bring people together and it’s been fantastic….it benefits communities and victims…one on one but also the community level.”[25]

The development of this ‘anti-hate crime community’ is very welcome, however there are signs that it isn’t as inclusive as it could be. Questions remain on its accessibility to national organisations recording and monitoring disability and anti-racist crime.

The issues highlighted here are discussed in further detail in the following sections and in the recommendations.

Spotlight on Police-CSO cooperation

The Facing all the Facts research across the partner countries found that data and information-sharing take place in a number of forms and to varying degrees across a range of public institutions including the police, prosecution services, the courts and government departments.[26],[27] It is also commonly the case that information isn’t shared across public authorities, resulting in very limited information on the number of hate crime investigations, prosecutions and sentences. In most countries, where it takes place at all, sharing data and information between public authorities and CSOs is usually sporadic, tending to centre around specific, often high profile, or sensitive cases. In England and Wales, however, there is a different approach. As shown in the systems map, institutional connections are based on relatively effective frameworks and action, and systematic information sharing has been in place for some years for several communities.

The approach in England and Wales is perhaps the strongest example of public authority-civil society cooperation on reporting and recording hate crime in the world. While the technical elements of national information-sharing agreements are presented in the systems map, the story of how these protocols were established in England and Wales is presented as a case study in the project’s online learning for decision-makers with responsibilities for hate crime recording and data collection. Their experience can provide learning and possibly inspiration for decision-makers outside the UK.

Since the Macpherson Report, there have been clear and sustained political and institutional expectations pushing public authorities to constructively engage with community organisations. The research in England and Wales has focused on the most effective elements of specific, national CSO-public authority partnerships on hate crime recording and data collection, finding evidence of deep and constructive connection. The principles and practice of ‘critical friendships’, perception-based recording as a technical mechanism for connection and information-sharing protocols have been identified as key to developing these relationships.[28] However, the bulk of the burden of ‘making it happen’ can often fall to NGOs, and the challenges of navigating this terrain in a context of – at times– polarising politics and sustained austerity with limited and, often short-term, resources can be overwhelming.

In addition, as shown in the systems map, there is currently an obvious and unsettling gap in the inclusion of specialist organisations on racist and disability hate crime in national inter-institutional national frameworks and action on hate crime reporting and recording, which is the focus of the next section.

Spotlight on strategic efforts to improve institutional cooperation on reporting and recording of racist crime

Many local and regional organisations supporting victims of racist crime have very good relationships with the police and regularly cooperate in ad-hoc information sharing, training and victim support referrals. However, as highlighted in the systems map, there is currently no dedicated organisation with national coverage that has an effective system to record racist offences or to support victims of racist crime.[29] As a result, there is no national information-sharing agreement specifically for Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) communities. This is surprising considering reports and records of racist crime are by far the most numerous in England and Wales.[30]

In its 2016 Hate Crime Action Plan, the government reported that it, ‘heard concerns that the debate over emerging hostilities such as religion had meant that the national debate and focus on race hate had diminished.’[31] It is of course essential to focus on securing effective frameworks and action on antisemitic and anti-Muslim hate crime. Doing so should not be offered as an explanation for why the focus on racist crime has ‘diminished’. Rather, equal focus across the ‘strands’ and an effort to highlight and address their complementarity and intersectionality should be made. In any case, barriers to building national reporting and recording partnerships on racist crime need much deeper exploration, and include a consideration of the following issues:

- The closure of Race Equality Councils and the ‘folding in’ of racist crime into the overall ‘hate crime’ policy and practice space has diluted focus and resources on evidencing and addressing racist violence in a systematic way across the country.

- Organisations working on issues affecting Black communities are likely to prioritise work on areas of most common concern for communities such as Stop and Search and other evidence of disproportionality in policing and the criminal justice system, especially in the context of extremely limited and short term funding available to community groups as a result of a sustained ‘austerity’ programme in England and Wales. CSOs have had to take difficult decisions on what to prioritise.

- Communities affected by racist crime are large, disparate and diverse. It might be unrealistic to expect that one or even a small number of organisations can effectively engage in single national partnerships on reporting and recording, while keeping the trust and confidence of all communities.

The government’s longstanding obligation to regularly report on statistics on race and the criminal justice system enshrined in Section 95 of the Criminal Justice Act 1991 evidences disproportionality in decision-making on the grounds of race, involving black and minority ethnic (BAME) people as employees, suspects, defendants, prisoners and victims, including as victims of racist crime. The recent Lammy Review drew on official evidence of disproportionality to explore its impact on BAME people, concluding,

‘…the criminal justice system (CJS) has a trust deficit with the BAME population born in England and Wales.’[32]

The extent to which people’s perception and experience of disproportionality undermines their willingness and confidence to report racist crime must be better understood and addressed in visible and effective ways, a point which is addressed in the recommendations section.

Disability hate crime

As detailed in the timeline, disability hate crime has emerged as an important policy concern in recent years. Both the police and Crown Prosecution Service have invested significantly in policy, practice and engagement to describe and explain the key features of disability hate crime investigation and prosecution. However, as detailed in the systems map, reporting and recording are still very low compared to other strands. Similarly, to racist crime, while many local and regional organisations supporting victims of disability hate crime run good services, have effective relationships with the police, and regularly cooperate in ad-hoc information sharing, training and victim support referrals, there is currently no community organisation with national coverage that has an effective system to record disability hate crime offences or to cooperate with the police on information sharing and support. As a result, there is no national information-sharing agreement specifically for disabled communities.

Some reasons for this are similar to those listed above in the context of racist crime, however there are also different issues to consider.

- Campaigning organisations working on disability have had to prioritise their energy on evidencing and combating the disproportionate and sometimes devastating impact of austerity on disabled people and the support that they receive.[33] This limits their ability to dedicate time and energy to developing effective hate crime reporting, recording and support services.

- ‘Disabled people’ comprise a disparate and diverse community that might not lend itself to creating a single recording and reporting body.

- A tendency to understand violence against disabled people as a ‘safeguarding’ problem as opposed to a policing and broader criminal justice issue diverts attention and resources away from addressing the problem as one of hostility and prejudice against disabled people.[34]

Although not explored in detail here, from the perspective of the police and other public authorities, the range of issues on which to engage across crime and criminal justice policy in the shared context of austerity can also be overwhelming.[35] There can be an understandable desire to secure relationships with a small number of organisations, which ‘represent’ communities. However, this approach is not always realistic or possible for large and sometimes disparate communities that might need a number of organisations to more fully represent their experiences and needs. These points are particularly pertinent when considering how to address the evidenced gaps in national relationships relating to racist and disability hate crime and to a lesser extent, anti-Muslim hate crime.

Assessing and reducing the recording and reporting gap: future steps in policy and practice

As set out in the self-assessment framework and systems map, there has been significant progress in reducing the gap between the number of hate crimes recorded by the police and the number of hate crimes estimated by the Crime Survey for England and Wales. In 2017-2018 police-recorded hate crime increased by 17% compared with the previous year.[36] This figure is consistent with the upward trend in recent years: the number of hate crimes recorded by the police has more than doubled.[37] As explained by the Home Office, ‘This increase is thought to be largely driven by improvements in police recording although there [have] been spikes in hate crime following certain events such as the EU Referendum and the terrorist attacks in 2017.’[38] Police recording is increasing in the context of an overall reduction in crimes estimated by the Crime Survey for England and Wales, further suggesting that the increase in police-recorded crime is due to better recording and possibly better reporting rather than an actual increase in hate crime over time.[39] This development is to be welcomed and is an indicator that sustained and focused work to improve reporting and recording across the country has had a positive impact.

However, persistent problems in police recording remain. As detailed in the systems map (see police-victim relationship), the gap between hate crimes recorded by the police and the much larger number estimated by the CSEW is not only caused by under-reporting by victims, it is also due to mistakes in police recording of hate crime.[40] HMICFRS identifies police call handlers as a critical interface between potential hate crime victims and the police and concludes that steps need to be taken to improve their ability to identify hate crime. The report recommends that call handlers are directed to ask open questions to ascertain victim perception and that training is made available to this target group.[41]

The interface between victims and alternative forms of reporting, or ‘third party reporting’ is also crucial.[42] Wong et al (2019) distinguish between third party reporting services and third party reporting centres. As set out in the systems map, specialist organisations such as CST, Tell MAMA, Galop and Stop Hate UK, provide national third party-reporting services, mainly through online reporting, texting services and helplines. These services usually provide direct support and share information on hate incidents in accordance with the terms of nationally agreed information sharing protocols with the police.

Third party reporting centres tend to be hosted by non-specialist organisations in physical locations such as libraries, social clubs, mosques, and day centres. Although the Hate Crime Action Plan pledges to increase the number of third party reporting centres as a key action to improve reporting,[43] there is significant evidence that reporting centres are not being used.[44] Research in Scotland found that 89.3% of respondents working at a third party reporting centres reported that the centre had either been inactive or not very active the previous year.[45] A 2014 review by the national policing hate crime group, cited in a recent HMICFRS inspection report, ‘Understanding the Difference’ found that: “many [reporting centres] failed to deliver tangible results’.[46] The HMICFRS concluded based on its own findings, ‘It appears that little has changed since this review….’[47]

A recent review of 35 third party reporting centres in two regions of England and Wales found that only one centre received dedicated funding and that most of the centres hadn’t received reports of hate crime in the previous 12 months.[48]

HMICFRS recommends a shift away from providing physical reporting locations to online methods as a way to save resources and to take advantage of the general move towards accessing services online:

‘the fact that hate crime increasingly takes place online, and the use of IT by victims to report offending (for example, by way of True Vision[49]), may mean that physical centres are increasingly outdated. Indeed, many forces have used these arguments to explain the closure of police front counters. It is also the case that with reduced resources, police forces and their partner organisations will find it increasingly difficult to keep up the commitment they need to maintain effective third-party reporting arrangements….This means forces and their partner organisations will need to assess their own arrangements continually in terms of value for money, and the benefits of community engagement.’[50]

However, a recent review of third party reporting in Hertfordshire by Chakraborti and Hardy found mixed levels of confidence expressed by victims in using online reporting platforms.[51] Some researchers have recommended that more work is done to find out why some approaches to third party reporting are more successful than others.[52] Wong et al have developed a third party reporting centre assessment tool.[53] Others point out that low levels of third party reporting suggest both a lack of awareness about the existence of these alternative routes, and a need to explicitly connect reporting with support thus giving motivation and a reason for victims to take what can be an intimidating step.[54] Wong et al (2019) conclude, ‘…adopting third party reporting centres as an orthodoxy to improving hate crime reporting and recording is at best unproven and on the current (limited) evidence, seriously in doubt’.[55]

The usual focus on ‘closing the reporting gap’ misses a strategic consideration of what actually motivates victims and witnesses to report and how this relates to core public authority duties to reduce and prevent crime, and increase access to justice and support for victims. The next section draws on conversations about the aims and purpose of hate crime reporting and recording with people at the centre of these efforts, and tries to identify ideas for consideration, discussion and recommendation.

Time for a re-think?

‘….what is the target, what are we trying to achieve? An increase by 10%…? But an increase of 10% isn’t a long term strategy. That isn’t getting to people….How do we deal with the volume if we are successful, and give the right response? What is [our] foundation for dealing with this and how [can we] make sure that people have a good first conversation?’[56]

The questions posed above raise two crucial points. First, it is unclear whether police forces have the resources to cope with a doubling of reported and recorded hate crimes.[57],[58] Second, the interviewee points to the crucial question: how to ensure that the first response or ‘conversation’ with the police or a third party, is effective and appropriate? Answering this question gets to the heart of the strategic importance of improving hate crime reporting.

A single, reported hate crime or hate incident can be a part of a ‘process of victimization’,[59] not all of which is reported. Incidents take place over time and in different forms and locations, and include criminal and noncriminal acts. Many victims may know that they have been targeted because of hostility towards their identity but not that it is called a ‘hate crime’ or that they are entitled to a particular response under the Victim’s Code of Practice. Getting to ‘what happened’ needs unpicking, often through conversation with a victim or witness who might not fully understand themselves what is happening.[60] The right response might require a mix of risk assessment, referrals to support and consideration about the right remedy, whether criminal and/or civil.

At the moment, not much is known about whether those reporting hate crime are having a good interaction with the police and with third party reporting services. As set out in the systems map, the Crime Survey for England and Wales 2017-2018 reported that hate crime victims are significantly less satisfied with the police response than victims of all crime.[61] Even less is known about the satisfaction of those reporting to specialist services and the need for independent evaluation of current services was expressed in the interviews.[62]

The next sections examine the relationships between reporting and support, protection and access to justice and propose a strategic model to understand and realise these connections for the benefits of victims and communities.

Reporting into support

‘Is success getting as many reports to the police as possible or as many prosecutions as possible or is success getting as much support to victims out there as possible, depending on what they might need?’[63]

This quote points to the problem that the aim of closing the gap between reported and unreported crime and/or increasing the criminal justice response can often be presented as competing with the aim of increasing access to support. In fact, it is vital to find strategies, policies and funding approaches that recognise the interdependence of these aims.

Although support services for victims of crime are enshrined in the Code of Practice for Victims of Crime[64] and the EU Victims’ Rights Directive,[65] there is a lack of strategic narrative about the fundamental connection between reporting and support. Evidence suggests that reporting functions that are either set up without integral support services or seamless referral to support and outreach are less likely to be effective.

Disconnecting reporting from supporting

Research undertaken in Northumbria illustrates that as the support element of a third party reporting network, Arch, was reduced and then stopped, the number of reports it recorded drastically reduced.[66] In 2011 the Arch network was comprised of 140 organisations and three members of council staff whose jobs included community outreach and conflict resolution. In 2012 the network recorded its highest number of over 800 incidents. However, by 2015, this figure declined to 64. During this period, a large number of organisations closed and membership of the network declined by 50%. Arch’s staff team was cut and their functions moved to local authority staff with ‘other existing and often unrelated roles’, leaving Arch as, ‘only a monitoring tool and a database’.

The first and ongoing ‘conversations’ with people undergoing a ‘process of victimisation’ require an assessment of their support needs alongside encouragement to report directly to the police or an agreement to have the anonymised details of the incident passed onto the police on their behalf. More research should be undertaken to evaluate the effectiveness of connecting support to reporting by both the police and third parties.

Reporting into protection and prevention

Accurate and real-time data about hate incidents are essential for the police to fulfil their core function: to prevent and reduce the risk of crime and victimisation.[67] This function has two core aspects to it. The first relates to using information to plan for critical incidents. For example, the recent ‘punish a Muslim day’ incident involved letters being sent to Muslim communities outlining ‘punishments’ to be given to Muslims on a specific day. As information about the letters were shared throughout the UK – and internationally – the specific threat that individuals would be inspired to act on the letter grew. Relying on their established information-sharing agreement, Tell MAMA and the police worked very closely, with daily cooperation, sharing information about reports and other information, to address risk and agree methods of communication with communities to provide reassurance. In this instance, communication strategies were also shared because of the competing objectives to reassure communities whilst reducing the risk of motivating potential perpetrators.

The second aspect of the police core function to reduce crime and prevent victimisation relates to assessing the risks of revictimisation or escalation that individual victims face and ensuring the effective deployment of police resources and support services. There is evidence that there is not a consistent approach to risk assessment in this area. As set out in the systems map (see victim-police relationship), Operational Guidance sets out recording obligations and directs police to conduct needs assessments, however the HMICFRS Inspection found that the framework was insufficiently detailed, concluding that, ‘The lack of national direction means that the type and level of service victims receive depend on where they live.’[68] The Inspection found that 12 forces have a bespoke hate crime risk assessment, 18 use a generic risk assessment that applies to all victims, five use a risk assessment for hate crime which relates to anti-social behaviour and eight have no secondary risk assessment process. The inspection states, ‘…in our case assessments, we found that only 56 out of 180 had an enhanced risk assessment completed. This is deeply unsatisfactory.’[69],[70]

Guidance to third party reporting services on identifying and addressing risk is also patchy. The Third Party Reporting Protocol asks if an individual is at risk, and if so it is recommended that the police are notified. However, there is no guidance on how to carry out a risk assessment or how to capture information in a way that is most useful for the police. The RADAR guide to setting up third party reporting centres includes detailed guidance on what to do if a victim faces a high risk, however, there is no specific risk assessment tool included.[71] CST guidance does not include guidance on the topic.[72] GALOP’s hate crime quality standards also emphasise the importance of risk assessment.[73] However, none of the guidance identified in this research includes specific risk assessment tools for hate crime cases.

Identifying the improved assessment of risk as a strategic aim of hate crime reporting policy prioritises the crucial need to both improve the intelligence picture relating to specific incidents and trends and to reduce risks faced by victims and communities.

Reporting into justice and the right remedy

Very often, if not most of the time, whether a case can progress to a prosecution relies on the evidence of the victim. As such, hate crime reporting is fundamentally connected to securing equal access to justice and, ultimately, ensuring that the court has the chance to apply hate crime laws where the offence is proven.

Access to justice is also about finding the right remedy for the situation and to consider what victims actually want as a result of taking action to report. As one interviewee pointed out, ‘a criminal justice response is one way of addressing the issue of hate crime but there are all sorts of other issues – housing, health, etc.’[74] Another interviewee explained, ‘many people don’t want a criminal justice outcome.’[75]

Meeting these needs requires a high level of skill, knowledge and relationships across the system, which are not currently in place, as can be seen on the systems map. In particular, connections across criminal justice, police and housing authorities are essential, yet, in the context of austerity, the path to progress is unclear.

Connecting the dots: Towards a strategic framework on hate crime reporting and recording

Early consultation with stakeholders was positive about re-thinking approaches to third party reporting, introducing minimum standards for CSOs and undertaking evaluation. However, as one respondent put it, the ‘devil is in the detail’.[76] Any future work would also take place in the context of years of ‘austerity’. This section brings together research findings and the outcome of discussions at the national consultation meeting held in London in November 2018 to present a strategic framework on hate crime reporting and recording.

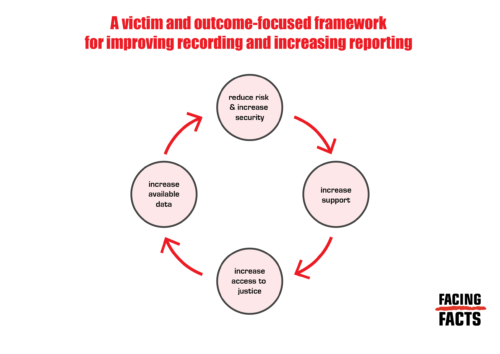

Closing the gap between reported and unreported crime has been the government’s focus to date, yet evidence is suggesting that what is needed is an approach that spans all actors with responsibility and better integrates hate crime reporting and recording with these other connected strategic aims:

- risk is identified and reduced;

- the right first response and support is secured; and

- positive outcomes for victims and communities are achieved, including access to justice.

The graphic below presents a victim and outcome focused strategic framework on increasing reporting and improving recording.[77] The final recommendations section presents issues to consider for implementation in England and Wales.

Using the data that we have

Policy makers, practitioners and NGOs have a tremendous amount of data and evidence available to them from official sources, NGO reports and research, which sets out the context of hate crime, describes the impact on victims and communities and points to effective practice. However, it is unclear to what extent national and local data is used to assess performance and identify ways forward. In the context of the hate incident recording by the police, HMICFRS concluded,

‘… while forces and the government encourage members of the public to report hate incidents and crimes, apparently some forces, or the government, do little with some of the resulting information. This is a missed opportunity to identify emerging trends and compare differences and possible gaps in recording practices between forces. From the information forces gave us, we have given a general analysis [that] illustrates that far more could be made of this information than is now the case. We accept that there are sometimes differences between forces in the way that incidents are recorded, but we think the benefits of this approach outweigh these considerations’ [78]

The impact of austerity as a barrier to securing routes to reporting and support

England and Wales’ precious progress in establishing the most comprehensive national picture of hate crime in Europe is under threat. Many local specialist organisations have closed or are at risk of closing down, leaving victims and communities without support. Those that survive are chasing ever decreasing resources, risking destructive competition with important allies and draining precious staff time that would be better spent supporting victims and building partnerships.

The impact on relationships with public authorities can be damaging. One public authority representative explained, ‘Some of the issues that we have had of late is that some orgs don’t have funding, some groups that we used to work with don’t have capacity. That has created a vacuum for us…we have had to work across regions to pool resources…there are some challenges…but with the increase of extreme-right activity we have to find ways of forging ahead and working in ways that are supportive and mutually respecting.’[79]

NGO interviewees pointed to the problem that public sector partners and funders do not always grasp the current challenges faced by NGOs. For example, limiting funding to 6 -12 months, or to a set of training sessions as opposed to commissioning a comprehensive service. These issues pervade this report’s findings and have implications for the delivery of its recommendations.

Ways need to be found to reverse this trend and target funding to the most skilled existing services as well as to support the development of effective services for under-served groups.

Shifting the narrative

In efforts to get hate crime on the agenda, there can be a tendency to focus on evidence that suggests that hate crime is ‘on the rise’. As shown in the timeline, spikes in hate crime followed the 2016 Referendum, and domestic and international terrorist attacks, and civil society organisations have been reporting significant increases in reports to their services.[80] In addition, there have been recent increases in hate crimes on the grounds of sexual orientation and religion in 2017-2018 (see table below)[81], as presented in the table below, evidence from the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggests a longer term and overall decrease in the incidence of hate crime.

Comparative table of hate crime estimates from the Crime Survey for England and Wales from 2011- 2018[82]

[table responsive=”yes” alternate=”no” fixed=”no”]| 2011/ 12- | 2012/13 – | 2015/16-2017/18[83] | |

| 2012/13[84] | 2014/15[85] | ||

| Race | 154,000 | 106,000 | 105,459 |

| Religious | 70,000 | 38,000 | 39,000 |

| Sexual orientation | 39,000 | 29,000 | 30,000 |

| Disability | 62,000 | 70,000 | 52,000 |

| Gender identity | Unreliable | Unreliable | Unreliable |

While there is evidence that the downward trend is reversing for hate crimes based on hostility towards religious identity and on the grounds of sexual orientation, police-recorded figures show that reporting by the public and recording by the police has risen signficantly.[86] These are positive developmentsand suggest an increased public awareness of the problem and improvements in public authorities’ and civil society organisation practice after many years of hard work and focus.[87]

Much work remains to be done. Evidence presented in this report and gleaned from victimisation surveys, police-recorded crime figures, research, inspection reports and civil society data points to the most important and urgent problems that need to be addressed. For example:

- Reporting is on the rise, however, the problem of under-reporting, particularly for some groups, stubbornly persists.

- Police-recorded hate crime is on the rise, however there remains an unacceptable gap between reporting and recording, suggesting that the police are not following their own perception-based recording policy.

- Specialist organisations have established ground-breaking practice yet insufficiently thought-through third party reporting policy has redirected precious resources away from specialists, without demonstrable positive effect.

- The HMICFRS Inspection found an inconsistent and therefore dangerous approach to risk assessment, and patchy access and referral to support services, leaving victims without any help.

- Twenty years after the Macpherson Inquiry, which directed public authorities to focus their efforts on strategic relationships with BAME communities, low levels of trust are probably a factor in the lack of national information sharing agreements and strategic partnerships between BAME organisations and the police.

- Civil society organisations are struggling after years of ‘austerity’ have cut access to funds, engendering unhealthy competition across the sector.

Hate crime should not need to be on the rise to attract the serious attention as a public policy priority it deserves. More work is needed to understand differences across community experiences and across data sources. For example, figures from the Community Security Trust suggest a steady increase in antisemitic incidents. This evidence is difficult to check against crime survey data, which does not provide separate data on antisemitic and anti-Muslim hate crime. Further, data on hate crime prevalence and impact should be understood in the context of data on discrimination in the criminal justice system and beyond. For example, existing data from ‘Section 95 reports’, which point to discrimination on the grounds of race should be brought into an analysis of why victims might not report or remain engaged in the criminal justice process. Similar obligations to measure these outcomes for other groups should be considered and commissioned.

Recommendations and conclusions

Recommendation 1: Continue to move forward on existing plans to create a cross-CJS electronic recording and data sharing system.

Some elements of this delivery through the single ‘common’ platform were expected to be delivered in 2016 and delays have prevented progress to this objective. It is recommended that officials assess current progress and agree a ‘roadmap’ and timeline for completion of the IT systems that will allow complete and comparable hate crime data.

Recommendation 2: Prioritise a particular focus on BAME and disabled communities.

There are gaps affecting all communities at the regional and local levels, which need to be understood. However, the focus of this report has been on the national level, and the gap in recording and reporting relationships for BAME and disabled communities is most glaring.

Working groups with relevant representation should be established to:

- Constructively assess and problem-solve the impact of perceptions of institutional racism on both the willingness of individuals to report experiences of hate crime as well as the willingness of civil society organisations to engage in national hate crime reporting and recording policy and action.

- Invest in building networks of BAME and disabled communities that can effectively engage in hate crime reporting and recording efforts at the national level.

In particular, it would be important to look at racist crime and responses in more detail, for example:

- Can crime surveys indicate the most targeted groups within BAME communities?[88]

- What are the most common barriers facing community organisations and public authorities at the local and national levels when it comes to cooperation in this area?

- Are there examples of positive cooperation? For example, it is recommended that the work of Stand Against Racism and Inequality, SARI is looked at in close detail as an organisation with a well-defined recording methodology and a track record of community confidence and public authority engagement.

- What might a networked information-sharing agreement look like? The current model of information-sharing agreements shared with single organisations might not be realistic for BAME communities. One proposed solution to diverse, large community reporting could be to have an ‘umbrella group that would provide a “funnel” for reporting into the police and others.

On disability hate crime:

- invest in the development of effective third party hate crime recording and reporting mechanisms for disability, working towards a national MoU, drawing on the expertise of CST, Tell MAMA, Galop and Stop Hate UK.

Recommendation 3: Adopt a strategic approach to increasing reporting and improving recording

The current government policy of ‘closing the reporting gap’ and ‘increasing the number of third party reporting structures’ needs a re-think. The Home Office and relevant partners should clarify the strategic objective of third party reporting policy, using our proposed framework as a starting point. Based on the agreed strategic framework, a review of third party reporting should be commissioned and delivered by a partnership that works closely with public authority and civil society experts. The review should take account of evidence cited in this report and define the functions that need to be delivered to achieve full coverage across all types of hate crime in all geographical regions.

The review should consider the following:

- Adopt a comprehensive and aligned approach on risk assessment for victim support and deployment purposes. In line with the recent HMICFRS Inspection, the police should be required to establish risk assessment and risk management processes to consistently plan and prioritise police deployment decisions and support referrals. Involve key CSOs and other agencies and draw on relevant research findings to integrate third party and police risk-assessment approaches and tools. Review and revise current third party reporting protocol – in light of findings http://www.report-it.org.uk/files/third_party_reporting_flowchart_1.pdf

- Victims of hate crime do not consistently receive an adequate first response when reporting to the police. Partners should come together to specifically identify what needs to be put in place across CSOs and the police to ensure that victims have the right ‘conversation’ when reporting what’s happened to them.[89]

- Within this, an effective conversation needs to be had about achieving a balance between highly specialist and more generalist services. If the aim is to improve reporting and support routes to and through the existing skilled organisations as well as to increase recorded figures, then perhaps the aim should be to extend and develop the reach of existing organisations that already create safe, skilled and knowledgeable spaces (in person, on the phone, online) for victims to report to. Ideally, these organisations deal with the immediate issues (what happened? emergency report to police? other non-crime immediate need?), provide support and pass high quality data for police intelligence, risk assessment and statistics. Local, established structures need to be built upon, not reinvented, and feed into the national pool of information and relationships.

- Consider whether there should be a minimum obligation on third party reporting structures that receive public money to report anonymised information to the police for risk assessment?[90]

- Integrate research findings on why victims don’t report into service design and commit to independent evaluation. Review where specific needs of victims are not met by current services.

- Clarify the role of CSOs in preparing Community Impact Statements.[91]

- Consider how to meet the needs of underserved groups and those that are victims of targeted violence outside the monitored strands including people working in the night time economy and homeless people.

- Support this work by establishing a national subgroup on improving reporting, recording and support with representation across public authorities and relevant CSOs. Explicitly connect this to a government-led strategy group.

Recommendation 4: Use the data that we have.

- Consider ways to bring together available data to understand the prevalence and impact of hate crime and how well responsible organisations are responding to the problem. More specifically, consider requiring police and other public authorities to regularly report on how information is used to reduce risk, increase support and increase access to the right remedies.

- Add Section 95, Race and the Criminal Justice System reports to the True Vision site and integrate the findings into broader strategies and narratives that counter and respond to hate crime, recognise the importance of a representative workforce, and the negative impact on reporting of disproportionality in Stop and Search, arrests, prosecutions, convictions and prison sentences on Black and minority-ethnic communities.

- Consider commissioning a report similar to Section 95 for all monitored strands of hate crime.

Recommendation 5: A focus on the role of education and housing authorities – deliver on Recommendation 17 of the Macpherson Report.

Recommendation 17 of the Macpherson Report called for the involvement of schools and housing authorities in recording and sharing data on hate crime and hate incidents, however there has been limited progress to date. Stakeholders should review and address barriers to involving these authorities and seek to involve them in the review and implementation of future hate crime reporting and recording strategy.

Government should consider whether it is still supportive of the principles of Recommendation 17 and if so actions to address the contribution of other state actors should be included in the next Government Hate Crime Action Plan.

Conclusions

Connecting on hate crime data in England and Wales has aimed to make a specific contribution to the already sophisticated framework of practice and research that has developed over the 20 years since the publication of the Macpherson Report. The learning and experience developed by leading practitioners across the police, CSOs, CPS and policy makers has been drawn on to develop case studies for inspiration and thematic insights across Europe. At the national level, this report suggests that progress is challenged by sustained austerity and a somewhat limited focus on reducing the reporting gap. The next stage in England and Wales’ journey should aim to make real what it means to ensure that victims and communities are reporting into a system that leads them to support, increased safety and access to justice. The roles and responsibilities of all relevant public authorities, including those responsible for housing, education and health, should be as clear as they currently are for the police and CPS. The innovative cooperation developed over the years across highly skilled NGOs that have the trust and confidence of their communities should be deepened and invested in. It is hoped that the findings and recommendations reported here help in achieving these aims.

Bibliography & Endnotes

Books

Chevalier, J.M., and Buckles, D.J. (2013) Participatory action research: Theory and methods for engaged inquiry. 1st ed. New York: Routledge.

Roulstone, A., Mason-Bish, H. eds. (2013) Disability, hate crime and violence. Oxon: Routledge.

Journal Articles

Bergold, J., Thomas, S. (2012) ‘Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion’. Forum: Qualitative Social Research. 13(1)

Clayton, J., Donovan, C. and Macdonald, S.J. (2016) ‘A Critical portrait of hate crime/incident reporting in North East England: The value of statistical data and the politics of recording in an age of austerity’. Geoforum, 75, pp.64-74. Available from: <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.07.001 >

Perry, J. (2009) ‘At the intersection: hate crime policy and practice in England and Wales’. Safer Communities, 8(4), pp.9-18

Perry‐Kessaris, A. (2019) ‘Legal Design for Practice, Activism, Policy, and Research’. Journal of Law and Society, 46(2), pp.185-210

Perry, J., and Perry-Kessaris, A. (2019) ‘Participatory and designerly strategies for sociolegal research impact: lessons from research aimed at making hate crime visible’. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3387479

Walters, M. A., Paterson, J., Brown, R., McDonnell, L. (2017) ‘Hate Crimes Against Trans People: Assessing Emotions, Behaviors, and Attitudes Toward Criminal Justice Agencies’. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi: 10.1177/0886260517715026

Wong, K. and Christmann, K. (2008) ‘The role of victim decision making in reporting of hate crimes’. Safer communities, 7(2), pp.19-35

Wong, K., and Christman, K (2016) ‘Increasing hate crime reporting: narrowing the gap between policy aspiration, victim inclination and agency capability’. British Journal of Community Justice, 14(3), pp. 5-23, ISSN: 1475-0279

Wong, K., Christmann, K., Rogerson, M., & Monk, N. (2019). ‘Reality versus Rhetoric’: Assessing the Efficacy of Third Party Hate Crime Reporting Centres. International Review of Victimology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758019837798

Legislation

Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 (UK). Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2001/24/part/5

Criminal Justice Act 1991 (UK) s 95. Available from: <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1991/53/section/95

Crime and Disorder Act 1998 (UK). Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1998/37/contents

The Criminal Justice Act 2003 (England and Wales). Available from: <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/44/section/146>

Criminal Justice and Immigration 2008 (UK) s 74. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/4/part/5/ crossheading/hatred-on-the-grounds-of-sexual-orientation

Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (UK). Available from: <https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/10/contents>

Public Order Act 1986 (England and Wales) s 18. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1986/64/section/18>

Racial and Religious Hatred Act 2006 (England and Wales). Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/1/contents

Directive 2012/29/ EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 201 establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2001/220/JHA. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ TXT/?qid=1421925131614&uri=CELEX:32012L0029, [accessed on 14 August, 2019].

Other

Antjoule, N. (2016). LGBT hate crime quality standard: a service improvement tool for organizations. [Online]. London: Galop. Available from: <http://www.galop. org.uk/wp-content/uploads/LGBT-Hate-Crime-Quality-Standard.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Attorney General’s Office (UK) (2006). Report of the Race for Justice Taskforce. [Online] Available from: <http://www.report-it.org.uk/files/race_for_justice_ taskforce_report.pdf> [Accessed 28 April 2019].

Chakraborti, N. and Hardy, S.J. (2015). LGB&T hate crime reporting: identifying barriers and solutions. [Online]. Equality and Human Rights Commission. Available from https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/research-lgbt-hate-crime-reporting-identifying-barriers-and-solutions.pdf [Accessed 7 August 2019]

—— (2016). Healing the Harms: Identifying How Best to Support Hate Crime Victims. Available from:<http://hertscommissioner.org/fluidcms/files/files/pdf/Victims-Commissioning/ Healing-the-Harms—Final-Report.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Community Security Trust (2018) 2018 Annual Review, Available online at https:// cst.org.uk/data/file/2/c/Annual%20Review%202018%20-%20ER%20edit%20 web.1550505710.pdf, Accessed on 17 August 2019.

Community Security Trust and Home Office (n.d.). A guide to fighting hate crime. [Online]. Available from: <http://www.report-it.org.uk/files/hate_crime_booklet. pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Crown Prosecution Service (2004). Racist incident monitoring: Annual Report 2003/04. [Online]. London: Crown Prosecution Service. Available from: <http:// library.college.police.uk/docs/cps/rims03-04.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Crown Prosecution Service (2018). Hate Crime Annual Report 2017-18. [Online]. London: Crown Prosecution Service. Available from: < https://www.cps.gov.uk/ sites/default/files/documents/publications/cps-hate-crime-report-2018.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Disability Rights UK (n.d.). Let’s stop disability hate crime: a guide for setting up third party reporting centres. [Online]. London: Disability Rights UK. Available from: <http://report-it.org.uk/files/lsdhc_a_guide_for_setting_up_third_party_ reporting_centres_final_200212.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019 ]

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (2018). Fundamental rights report 2018. [Online]. Vienna: FRA. Available from: < https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/ files/fra_uploads/fra-2018-fundamental-rights-report-2018_en.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Equality and Human Rights Commission (2011). Hidden in plain sight: Inquiry into disability-related harassment. Report of an Inquiry. [Online]. United Kingdom: Equality and Human Rights Commission. Available at: < https://www. equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/ehrc_hidden_in_plain_sight_3.pdf > [Accessed 14 April, 2019]

HMICFRS (2018). Understanding the difference: the initial police response to hate crime inspection report. [Online]. London: HMICFRS. pp.48–49 Available from: <https://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/ understanding-the-difference-the-initial-police-response-to-hate-crime.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Home Office (2012) Hate Crimes, England and Wales 2011-2012, [Online]. London: Home Office. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crimes-england-and-wales-2011-to-2012–2 [Accessed 16 September, 2019].

—— (2013) An Overview of Hate Crime in England and Wales. [Online]. London: Home Office. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/ uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/266358/hate-crime-2013.pdf [Accessed 16 September 2019]

—— (2014) Hate Crime England and Wales, 2013-2014. [Online]. London: Home Office. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crimes-england-and-wales-2013-to-2014 [Accessed 16 September 2019]

—— (2015) Hate Crime England and Wales, 2014-2015. [Online]. London: Home Office. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crime-england-and-wales-2014-to-2015, [Accessed 16 September 2019]

—— (2016a). Action against hate: the UK government’s plan for tackling hate crime. [Online] London: Home Office. [Online]. Available from: <https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_ data/file/543679/Action_Against_Hate_-_UK_Government_s_Plan_to_Tackle_ Hate_Crime_2016.pdf>

—— (2016b) Hate Crime, England and Wales, 2015-2016 [Online]. London: Home Office. Available from, https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hate-crime-england-and-wales-2015-to-2016. [Accessed on 16 September 2019].

—— (2018a). Action against hate: the UK government’s plan for tackling hate crime – ‘two years on’. [Online] London: Home Office. [Online]. Available from: <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/748175/Hate_crime_refresh_2018_FINAL_WEB.PDF> [Accessed 7 August 2019 ]

—— (2018b). Hate crime, England and Wales, 2017/18: statistical bulletin. [Online]. London: Home Office. [Online]. Available from: <https://assets.publishing.service. gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/748598/ hate-crime-1718-hosb2018.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019 ]

Jansson, K. (2007) British crime survey: measuring crime for 25 years. [Online]. London: Home Office. Available from: <https://webarchive.nationalarchives. gov.uk/20110218140037/http:/rds.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs07/bcs25.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Lammy, D. (2017) The Lammy review: An independent review into the treatment of, and outcomes for, Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic individuals in the Criminal Justice System. HM Government. [Online]. Available from: <https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_ data/file/€643001/lammy-review-final-report.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Ministry of Justice (2005) The Code of Practice for Victims of Crime, [online] United Kingdom: Ministry of Justice, available online at https://assets.publishing.service. gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/476900/ code-of-practice-for-victims-of-crime.PDF, [Accessed on 17 August, 2019].

MacPherson, W. (1999) The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry, Report of an Inquiry [Online] United Kingdom: The Stationary Office. Available at: <https://assets. publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_ data/file/277111/4262.pdf > [Accessed 28 April, 2019]

Maguire, C. (2017). Hate crime and third party reporting centres: a mapping exercise. Scottish Commission for Learning Disability. [Online]. Glasgow: Scottish Commission for Learning Disability. pp. 12. Available from: <https://www.scld.org. uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Hate-Report-3.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, Home Office, Ministry of Justice. (2016). Hate crime action plan 2016 to 2020. [Online]. Available from: <https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/hate-crime-action-plan-2016> > [Accessed 14 August 2019]

National Police Chiefs’ Council (n.d.). Information Sharing Agreement. [Online]. Available from: <http://www.report-it.org.uk/files/galop_signed_data_sharing. pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

ODIHR Key Observations (n.d.). [Online]. Available from <http://hatecrime. osce.org/sites/default/files/documents/Website/Key%20Observations/ KeyObservations-20140417.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Runneymede Trust (n.d.). The Struggle for Race Equality an oral history of the Runneymede Trust, 1968-1988. [Online]. Available from <http://www.runnymedetrust.org/histories/index. php?mact=OralHistories,cntnt01,default,0&cntnt01qid=60&cntnt01returnid=20 > [Accessed 28 April, 2019].

Schweppe, J., Haynes, A. and Walters, M.A. (2018). Lifecycle of a Hate Crime. [Online]. Comparative Report. Hate & Hostility Research Group – University of Limerick. Dublin: ICCL. Available from: <https://www.iccl.ie/wp-content/ uploads/2018/04/Life-Cycle-of-a-Hate-Crime-Comparative-Report-FINAL.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Tell MAMA (2018) Beyond the Incident, Outcomes for Victims of Anti-Muslim Prejudice, Tell MAMA Annual Report, 2017, Available online at https://tellmamauk. org/tell-mamas-annual-report-for-2017-shows-highest-number-of-anti-muslim-incidents/, [Accessed on 17 August 2019]

Walters, M. A., Brown, R. and Wiedlitzka, S. (2016a). Preventing hate crime: emerging practices and recommendations for the effective management of criminal justice interventions. [Online]. Project Report. Sussex Crime Research Centre and The International Network for Hate Studies. Sussex, UK. Available from: <http:// sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/64925/1/Interventions%20for%20Hate%20Crime%20 -%20FINAL%20REPORT_2.pdf> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Walters, M. A., Brown, R. and Wiedlitzka, S. (2016b). Causes and motivations of hate crime. Research Report. Equality and Human Rights Commission. Report number: 102.

Walters, M.A., Wiedlitzka, S., Owusu-Bempah, A. and Goodall, K. (2017). Hate Crime and the Legal Process: Options for Law Reform. [Online]. Final Report. University of Sussex. Available from: <https://www.sussex.ac.uk/webteam/gateway/file. php?name=final-report—hate-crime-and-the-legal-process.pdf&site=539> [Accessed 14 August 2019]

Williams, M. (2019). The rise in hate crime in 2017-18: a genuine increase or just poor data? [Online]. ESRC Blog. Available from: <https://blog.esrc.ac.uk/tag/hate-crime/> [Accessed 7 August 2019]

Quarmby, K. and Scott, R. (ed.) (2008). Getting away with murder: disabled people’s experiences of hate crime in the UK. [Online]. London: SCOPE. Available from: < http://www.stamp-it-out.co.uk/docs/_permdocs/gettingawaywithmurder. pdf> [Accessed 14 August 2019]

[1] See https://internationalhatestudies.com/publications/ for a comprehensive and regularly updated library of research and publications relating to ‘hate studies’.

[2] The other countries taking part in this research are: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy and Spain. See the Methodology section of the European Report for a detailed account of how this research was designed and carried out.

[3] In terms of its conceptual scope, the research focused on hate crime recording and data collection, and excluded a consideration of hate speech and discrimination. This was because there was a need to focus time and resources on developing the experimental aspects of the methodology such as the workshops and graphics. International and national norms, standards and practice on recording and collecting data on hate speech and discrimination are as detailed and complex as those relating to hate crime. Including these areas within the methodology risked an over-broad research focus that would have been unachievable in the available time.

[4] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a detailed description of the research theory and approach of the project.

[5] See Methodology section of the European Report for a full description of the research methodology

[6] See Methodology section of the European Report for agenda and description of activities

[7] Given the complexity and longevity of hate crime awareness and activity in England and Wales, there is an inevitable risk that key events are missed from the timeline. The point was also made during the December 2018 consultation workshop that international events and incidents, such as those relating to the Israel -Palestinian conflict for example, can lead to incidents – antisemitic and anti-Muslim in particular – in the UK and could also be included here. The project tried to mitigate these risks in two main ways. First, the timeline can be amended following publication should an incident meet the criteria. Second, it could be useful to create community-specific timelines so that further detail on incidents and responses can be included. The aim of the project is to support stakeholders at the national level to work together and revise and amend tools such as the timeline, systems map to reflect national contexts. The Methodology section of the European Report suggests exercises and techniques to do this. The European Report identifies emerging themes across the six timelines presented in the national reports.

[12] See full references in the timeline above

[13] See Perry, J. (2009)

[14] The International Network for Hate Studies compiles and disseminates the latest research into all aspects of hate crime, much of it originating in the United Kingdom.

[15] Regular conferences, Hate Crime Awareness Week and the ‘No to Hate Crime Awards’ showcase best practice across public authorities and community organisations.

[16] See also Walters et al (2017), which researched responses to hate crime from investigation to sentencing and beyond and proposes a revised legal framework with the aim of redressing current inequalities and barriers to prosecution.

[17] The government has asked the Law Commission to review the current legal framework and review, ‘the adequacy and parity of protection offered by the law relating to hate crime and to make recommendations for its reform.’

[18] See Methodology section of the European Report for further detail

[19] Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018), p. 67.

[20] See Standards section of European Report.

[21] Based on interviews with individual ‘change agents’ from across these perspectives during the research.

[22] For a full description of the main stakeholders included in national assessments, and how the self-assessment framework relates to the ‘systems map’, see the Methodology section of the European Report.

[23] ODIHR (2014)

[24] See Methodology section of the European Report for instructions.

[25] Interviewee five

[26] Research has been conducted in Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy and Spain

[27] See also FRA (2018), and OSCE Annual Hate Crime Reporting Website, www.hatecrime.osce.org

[28] For a full discussion of these elements see the European Report.

[29] Stop Hate UK has a national presence and is a signatory to an information-sharing agreement with the Police. However, its hotline doesn’t have full national coverage and the organisation is not solely focused on reporting and recording racist crime or disability hate crime.

[30] Home Office (2018a)

[31] Home Office (2016) p. 15

[32] Lammy (2018) p. 36

[33] For current information about the impact of cuts to support services on disabled people see https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/,

[34] Roulstone and Mason-Bish (2013)