Perry, J (2019) Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Spain. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.

Download the full report in PDF here.

Introduction

If we are to understand hate crime[1], support victims and reduce and prevent the problem, there are some basic questions that need to be answered:

How many hate crimes are taking place? Who are the people most affected? What is the impact? How good is the response from the police? Are cases getting investigated and prosecuted? Are the courts applying hate crime laws? Are victims getting access to safety, justice and the support they need?

While ‘official’ hate crime data, usually provided by police reports, are the most cited source for answers to these questions, they only tell a small part of this complex story. Understanding what happens to cases as they are investigated, prosecuted and sentenced requires a shared approach with cooperation across government agencies and ministries with responsibilities in this area, however, the necessary mechanisms and partnerships are often not in place. Reports and information captured by civil society organisations (CSOs) can provide crucial parts of the jigsaw, yet connection across public authority- civil society ‘divides’ is even more limited.

The Facing all the Facts project used interactive workshop methods, in-depth interviews, graphic design and desk research to understand and assess frameworks and actions that support hate crime reporting, recording and data collection across a ‘system’ of public authorities and CSOs.[2] Researchers adopted a participatory research methodology and worked directly with those at the centre of national efforts to improve hate crime reporting, recording and data collection to explore the hypothesis that stronger relationships lead to better data and information about hate crime and therefore better outcomes for victims and communities.

What was found is that a range of factors are key to progress in this area, including the:

- strength and comprehensiveness of the international normative framework that influences national approaches to reporting, recording and data collection;

- technical capacity to actually record and share information and connect with other parts of the system;

- existence of an underlying and inclusive policy framework at the national level;

- work of individual ‘change agents’ and the degree to which they are politically supported;

- skills and available resources of those civil society organisations that conduct recording, monitoring and advocacy.

The research found that each national context presents a different picture, and none is fully comprehensive or balanced.

This national report aims to describe the context and current picture of hate crime reporting, recording and data collection in Spain to present practical, achievable recommendations for improvement. It is hoped that national stakeholders can build on its findings to further understand and effectively address the painful and stubborn problem of hate crime in Spain.

It is recommended that this report is read in conjunction with the European Report which brings together themes from across the six national contexts, tells the stories of good practice and includes practical recommendations for improvements at the European level. Readers should also refer to the Methodology section of the European Report that sets out how the research was designed and carried out in detail.

How did we carry out this research?

The research stream of the Facing all the Facts project had three research questions:[3]

- What methods work to bring together public authorities (police, prosecutors, government ministries, the judiciary, etc.) and NGOs that work across all victim groups to:

- co-describe the current situation (what data do we have right now? where is hate crime happening? to whom?)

- co-diagnose gaps and issues (where are the gaps? who is least protected? what needs to be done?), and;

- co-prioritise actions for improvement (what are the most important things that need to be done now and in the future?).

- What actions, mechanisms and principles particularly support or undermines public authority and NGO cooperation in hate crime recording and data collection?

- What motivates and supports those at the centre of efforts to improve national systems?

The project combined traditional research methods, such as interviews and desk research, with an innovative combination of methods drawn from participatory research and design research.[4]

The following activities were conducted by the research team:

- Collaborated with relevant colleagues to complete an overview of current hate crime reporting, recording and data collection processes and actions at the national level, based on a pre-prepared template;[5]

- Identified key people from key agencies, ministries and organisations at the national level to take part in a workshop to map gaps and opportunities for improving hate crime reporting, recording and data collection.[6] This took place in Athens on 17 May 2017.

- Conducted in-depth interviews with five people who have been at the heart of efforts to improve reporting, recording and data collection at the national level to gain their insights into our research questions.

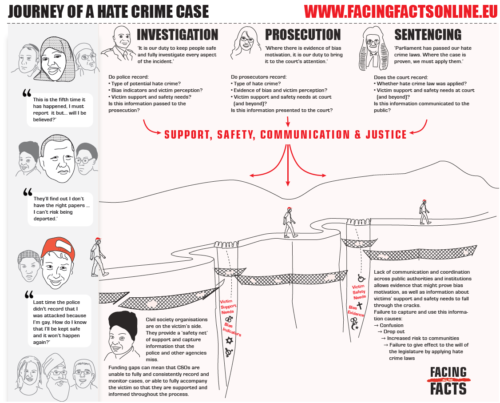

Following the first phase of the research, the lead researcher synthesised existing norms and standards on hate crime to create a self-assessment framework, which was used to develop national systems maps describing how hate crimes are registered, how data is collected and used and an assessment of the strength of individual relationships across the system. A graphic designer worked with researchers to create visual representations of the Journey of a Hate Crime Case (see below) and national Systems Maps (see ‘Spain’s hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’’ below). Instead of using resources to launch the national report, it was decided that more connection and momentum would be generated at the national level, and a more accurate and meaningful final report would be produced, by directly consulting on the findings and recommendations during a second interactive workshop which was held in Madrid, 2 October, 2018.

During the final phase, the lead researcher continued to seek further input and clarification with individual stakeholders, as needed, when preparing the final report. Overlapping themes from this and other national reports were brought together and critically examined in the final, European Report.[7]

The journey of a hate crime case

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[10]

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[10]

The Journey graphic conveys the shared knowledge and experience generated from this exercise. From the legal perspective, it confirms the core problem articulated by Schweppe, Haynes and Walters where, ‘rather than the hate element being communicated forward and impacting the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of the case, it is often “disappeared” or “filtered out” from the process.’[11],[12] It also conveys the complex set of experiences, duties, factors and stakeholders that come into play in efforts to evidence and map the victim experience through key points of reporting, recording and data collection. The police officer, prosecutor, judge and CSO support worker are shown as each being essential to capturing and acting on key information about the victim experience of hate, hostility and bias crime, and their safety and support needs. International norms and standards[13] are the basis for key questions about what information and data is and should be captured.

The reasons why victims do not engage with the police and the criminal justice process are conveyed along with the potential loneliness and confusion of those who do. The professional perspective and attitude of criminal justice professionals that are necessary for a successful journey are presented.[14] CSOs are shown as an essential, if fragile, ‘safety net’, which is a source of information and support to victims across the system, and plays a role in bringing evidence of bias motivation to the attention of the police and the prosecution service.

The Journey communicates the normative idea that hate crime recording and data collection starts with a victim reporting an incident, and should be followed by a case progressing through the set stages of investigation, prosecution and sentencing, determined by a national criminal justice process, during which crucial data about bias, safety and security should be captured, used and published by key stakeholders. The graphic also illustrates the reality that victims do not want to report, key information about bias indicators and evidence and victims’ safety and support needs is missed or falls through the cracks created by technical limitations, and institutional boundaries and incompatibilities. It is also clear that CSOs play a central yet under-valued and under-resourced role.

As in most countries, there is serious under-reporting of hate crimes to the police and to CSOs in Spain. There are also gaps in provision, support and information for victims, leading to drop out and poor outcomes. These points are addressed in more detail below where Spain’s ‘system’ of hate crime recording and data collection is considered in detail.

Click here to download the Journey in Spanish

Spain’s hate crime recording and data collection ‘system’

The ‘linear’ criminal justice process presented in the Journey graphic is shaped by a broader system of connections and relationships that needs to be taken into account. Extensive work and continuous consultation produced a victim-focused framework and methodology, based on an explicit list of international norms and standards that seeks to support an inclusive and victim-focused assessment of the national situation, based on a concept of relationships. It integrates a consideration of evidence of CSO-public authority cooperation on hate crime recording and data collection as well as evidence relating to the quality of CSO efforts to directly record and monitor hate crimes against the communities they support and represent.[15] In this way, it aims to go beyond, yet complement existing approaches such as OSCE-ODIHR’s Key Observations framework and its INFAHCT Programme.[16] The systems map also serve as a tool support all stakeholders in a workshop or other interactive setting to co-describe current hate crime recording and data collection systems; co-diagnose its strengths and weaknesses and co-prioritise actions for improvement.[17]

The interactive ‘Systems map’ below is best viewed in full screen mode (click on the icon in the top right hand corner of the map).

Click on the ‘+’ icons for an evidence-based explanation of the colour-coded relationship, based on international norms and standards.

Or download ‘Self-assessment grid on hate crime recording and data collection, framed by international norms and standards – SPAIN (PDF 474KB)‘

Commentary on systems map

Spain’s strategic and inter-institutional approach to understanding and addressing hate crime is generating relatively strong relationships across those bodies and institutions – public and nongovernmental – that have responsibilities related to hate crime reporting, recording and data analysis. The Ministry of Interior’s efforts to develop a comprehensive and strategic hate crime framework including a strong focus on hate crime reporting and recording for law enforcement is impressive and showing an impact. Its explicit focus on disability hate crime is particularly positive. OBERAXE serves an important coordinating function, developing effective connections across the system, with strong relationships with IGOs. The Prosecution Service has taken important steps including appointing specific hate crime prosecutors across the country, publishing prosecution guidance and data and critically evaluating its recording system. Disparities between police, prosecution and sentencing data suggest a lack of a shared concept of hate crime across the criminal justice system. There is a good commitment to transparency by the Ministry of Interior in particular and specific CSOs in their efforts to share, with the general public, what is being done to understand and address hate crime. This knowledge base could be greatly improved by researching and publishing victims’ experiences of hate crime through a full national victimisation survey. Movimiento Contra Ia Intolerancia is the most established CSO working on hate crime, with strong relationships with public authorities. Other CSOs are developing a stronger focus and competence in the area. CSO data is mainly qualitative. While this approach highlights the impact of hate crime on specific victims and shortcomings in the responses of public authorities, it doesn’t contribute to understandings of hate crime prevalence. In an exciting development, to which the Facing all the Facts workshops contributed, the National Office to Combat Hate Crimes set out its intention to work with CSOs to centralise information from CSOs that is reported to the Office and the police. This presents an opportunity to strengthen cooperation across CSOs activities in hate crime monitoring and support at the national and local levels. Work needs to be done to ensure that CSOs are sufficiently skilled and resourced to take advantage of this major policy development a point that is returned to in the recommendations.[18]

In terms of improving support to victims, inspiration might be taken from the structure and function of the Victims of Racial or Ethnic Discrimination Support Service, which offers support and independent assistance to victims of discrimination according to agreed protocols. A similar service and framework could be considered for victims of hate crime.

National context

The next sections give context to the ‘journey of a hate crime case’ and the ‘systems map’ and present themes gathered through the ‘connecting on hate crime data’ workshops and interviews with change agents at the centre of efforts to progress Spain’s work on understanding and addressing hate crime.

‘A big jump forward’

Spain’s progress in efforts to understand and address hate crime has taken ‘a big jump forward’ in the last 4-5 years.[19] One source of evidence of this ‘jump’ is the more than five-fold increase in the number of recorded hate crimes since 2013.

One interviewee explained,[20]

‘Right now, we have more hope than we’ve had in years. There have been changes in the last few years and we now see that the police, the district attorneys, the judges and the institutions have done some work … This has given us hope and we can now speak with more confidence that the fight against hate crimes is going somewhere.’

Spain’s progress was sparked by the implementation of its National Strategy against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and other forms of Intolerance , which is overseen by an actively coordinated inter-institutional steering committee, and underpinned by a cross government memorandum. The Committee includes representatives from across government departments and criminal justice agencies, as well as CSOs that are active in monitoring cases and supporting victims of hate crime. The key ministries lead and resource different elements of the strategy. For example, the Ministry of Health leads on anti-LGBTI hate crime while the Ministry of Justice leads on hate crimes based on hostility towards religious identity. The group has a rotating chair, with its members taking turns at the helm, and specific subgroups monitoring progress. The secretariat for the group is provided by the Observatory Against Racism and Xenophobia (OBERAXE),[21] which organises meetings, coordinates agendas and follows up on agreed actions, ‘it is quite a complex situation so that means that we need to be collaborating all the time’.[22]

The group focuses on four areas, delivered and monitored by four working sub-groups:

- hate speech;

- the analysis of sentences applied by the court;

- statistics, including hate crime recording and data collection; and,

- training.

In relation to the subgroup on hate crime recording and data collection, one interviewee explained an overarching goal as, ‘Trying to get a description of the situation in Spain…So first [we need] to know what the situation is and how we can improve and then we will also be able to evaluate whether we have made progress.’[23]

Elaborating on the motivation for this goal, she explained,

‘recording is essential to understanding the situation and we only get a part of what is going on…If we don’t have the first one, which is the notification and the recording of the cases then we cannot trigger all the system to support each victim, to evaluate the case and to give all the support. …So it’s not only data, it is data that provides a diagnosis of the situation but also data that helps us give support to the victim, which is at the end, our objective…which is to help them because it is a really difficult situation for a victim in this case.’

In addition to Spain’s overall strategic approach, individual agencies and ministries are taking focused action. For example, the National Office on Hate Crime within the Ministry of Interior has built on its first Action Protocol and is in the early stages of implementing its Police Action Plan to Combat Hate Crimes including specific, fully costed commitments and a clear structure of accountability. These are further detailed in the systems map under the relevant relationships.

Public authority-NGO cooperation: ‘partners in the same story’

Reflecting on what supports effective cooperation across public authorities and NGOs, one interviewee explained, “what probably helps the cooperation is when we both, when the public administration and the civil society feel that we are partners in the same story and we have to cooperate, no? And we have good relations with some of these NGOs. …When we are very much in our administration position and the NGOs are very much in their claiming position, I think we need to build a trusting environment to work. I think that we should be aware that we need to build this trusting environment on both sides.”[24]

OBERAXE’s cross-cutting position means that it works with NGOs in a range of policy areas and on specific projects, ‘Here in this general secretariat we have an important relationship with civil society because we manage quite a lot of European funds, directed to migration, including projects on racism and xenophobia, so we have an important relationship with NGOs and the projects they develop.’[25]

From the prosecutor’s perspective, one interviewee saw the purpose of cooperation as very practical,

‘…we want to have a point of contact, a reference so that if they come from civil society or the police and they want to report something that is going on and they want to deal with something that is going on that has to do with hate crimes they have a person with a specific name and surname that they will know and that will be the point of contact for everything that has to do with hate crimes. We have this list of the names in the region and we make sure that all of these lists are well known not just by us and the public administration but also civil society, the police and the NGOs and the different victims’ associations that deal with victims and work with them.’[26]

He described this cooperation as a work in progress that is accepted in theory but not always in practice. He highlighted the point that prosecutors are not experts

- even though they are appointed leads – and have many other tasks, and thus sometimes are tempted to look ‘for the easy solution’. Workshop participants also reflected that many prosecutors appointed as hate crime leads in fact do not have a hate crime expertise or enough time allocated for this role.

One interviewee, a member of staff at MCI, who has direct experience of hate crime and of the police from the time when he made a living from selling CDs on the street, added another layer to the challenges of cooperation on the ground,

‘If I am telling the truth, [police and immigrants], ‘will never find common ground….There are good people, there are good police, I know, I’m in the street and I’ve interacted with them. But there are many who are bad and are upset that we are here. It bothers them that we are here, too much.’[27]

In thinking about places for more positive and constructive connection with the police, he reflected, ‘I haven’t seen any place where we can go to voice our problems to the police’, and went on to consider what might improve this situation. He identified the possibility of setting up a neutral forum where people selling merchandise on the street might engage with the police and other local authorities to problem-solve. He concluded, ‘We’d like to have a forum to demand the chance to voice our concerns. This would be a good idea’.

A regional coordinator at MCI explained that NGOs often need to act as the ‘practical link’ between the police and victims. In one example, a victim was repeatedly racially harassed. Although she didn’t want to report the first incidents to the police, MCI was able to convince her to involve police colleagues as the harassment quickly escalated. Evidence that effective support increases the chance that a victim will report to the police is explored in detail in the European Report.[28]

An interviewee added another layer to the picture, identifying the necessarily deep trust between support services and victims of hate crime:

‘…in many cases for us immigrants, I am the link between them and the association….Because I am closer to my countrymen to know what’s hurting them, what are their problems…so that’s why I am working here… We’re here fighting so that everyone has the right to live their life. We’re here for everyone, so people can be where they want to be, without caring about if they are black or white, or homosexual’.[29]

One interviewee pointed to the importance of opposing hate crime in all its all forms and supporting all communities – without exception – as being fundamental to the hate crime approach:

‘Say I work for an anti-racism organisation. But you can be anti-racist and still antisemitic. I could fight against antisemitism, but still be islamophobic. I could fight against islamophobia and still be antisemitic. It’s these divisions and for that, we need to work against this dynamic…If we had organisations that addressed hate crimes holistically we would avoid the divisions among… organisations… The most effective strategy is when we are united… This has to happen everywhere else. Organisations need their main mission to be fighting against hate crimes. If this applies to everyone, it would be that much stronger.’[30]

CSOs have taken decisive action in tackling hate groups. Spain’s constitution provides for ‘popular actions’, which MCI has used to good effect. The Director of MCI explained,

‘We showed up to several trials. And we were able to get them to declare that certain hate groups were illegal, such as Hammerskins and Blood and Honour. And right now, we have various high profile racist and neo-nazi organisations accused of operating here in Spain. We are fighting them with popular action. With this freedom, there is a security risk, but the results that we have had, have been brilliant. These groups are becoming illegal and these people are going to jail, to prison. It’s diligent work, and if they send a message to organise an attack, to make hate crimes happen, to attack vulnerable people, then they’re going to jail just as their organisations.’

The next ‘big jump’?

As set out in the systems map and narrative, the strategic picture and measurable progress in Spain is very encouraging. An inter-institutional framework that supports cooperation both across public authorities and government ministries, as well as with CSOs is in place at the national level. The commitment to set up a mechanism to share data between the police and CSOs specified in the Ministry of Interior’s hate crime action plan provides an exciting opportunity to deepen connections with those CSOs that have a track record of monitoring and victim support and a potential blueprint to spread cooperation across the system. At the second workshop held in Madrid to consult on the emerging findings of this report, the group considered whether Spain is ready for its next ‘big jump’. As in all contexts, there are specific potential barriers to consider as well as the ever present pressure of limited funds and resources.

Research findings indicate that a lack of conceptual clarity about what should fall within the hate crime concept in reporting, recording and monitoring work is a potential barrier to progress in Spain. First, there are ongoing debates across stakeholders about the boundaries of the hate crime concept and whether groups such as police officers should be included within it. There are also differing views about how the protected characteristic of ‘ideology’ should be interpreted.[31] For example, recently issued prosecution guidelines includes as an instance of hate crime a physical attack against a ‘neo-nazi’. While this example makes the legal point that all kinds of ‘ideologies’ could be a target of hate, choosing it for inclusion in prosecutor guidelines can be alienating for the communities that hate crime strategies and policy should be aimed at.

Such debates are not particular to Spain; they are important to have and they are ongoing in the academic sphere and beyond.[32] However, at the level of policy implementation and practice, including groups that are not historic or current targets of broader discrimination and exclusion can weaken the effectiveness of efforts to protect those who are most at risk. As one interviewee explained, ‘the vast majority of CSOs support the idea to limit the concept of hate crimes to minority groups that are traditionally discriminated against’.[33] The current international normative framework also supports this general approach.[34]

Second, there is a lack of clarity about definitions of ‘hate crime’, ‘hate speech’ and ‘discrimination’. The systems map shows that most CSOs do not consistently disaggregate reports of hate crime, hate speech and discrimination in their monitoring and public reporting and that there is no shared definition of hate crime across the criminal justice system allowing cases to be tracked from investigation to prosecution and sentencing. Interviewees indicated that the situation could be improved by incorporating a specific definition of hate crime in Spain’s criminal code. In the more immediate future, the prosecution service and other agencies, could agree to implement current hate crime definitions used by law enforcement without legal changes. International standards support clear distinctions between hate crime and hate speech.[35]

The impact of international work and developments on Spain

Interviews and workshops identified international norms and standards relating to hate crime, and the increased focus by key intergovernmental organisations and agencies (IGOs)[36] on national actions in this area as having been important drivers in Spain’s progress.

For MCI, working on the issues for many years, IGOs are perceived as a crucial source of support: ‘until 2014 we were completely on our own… We had to obtain the support of Europe to change things. With Europe’s influence along with our own, we have made progress in changing public institutions and non-governmental organisations.’[37]

OBERAXE identified a sustained focus from IGOs on national approaches to hate crime as being very helpful in building national political support. Giving the example of Spain’s approach having been included in FRA’s ‘compendium of practices’, the head of the Observatory explained, ‘This recognition [from IGOs] is always important and it helps. Even at the [national] political level – which is important – they say “okay this is important” and they may provide more support to their own institutions to continue working on that line’.[38]

The lead hate crime prosecutor identified judgments from the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) as very influential in their approach to hate crime,

‘we use the ECHR [judgments] as our guide for what we should be doing…For example when we encountered these judges who say “come on, this [hate crime case] is not too serious”. What we tell to tell them is “no, we cannot treat this as a minor thing because look at what Europe is asking us to do.” Europe is asking us to see it from a different perspective and act accordingly so that is what we are trying to do.’[39]

While the central role played by IGOs in driving improvements at the national level is clear, arguably as important is the skill, motivation and commitment of those at the centre of national efforts. This highlights the need for targeted and relevant support to these ‘change makers’ to continue their efforts. This point is further developed in the European report.

Recommendations

Spain’s progress can serve as inspiration for other countries. The following recommendations aim to consolidate and support further progress, with a focus on better aligning efforts across public authorities and institutions and NGOs that are specialist and effective in recording and monitoring hate crimes and supporting victims.

Recommendation 1: Review knowledge and training needs of law enforcement personnel in all national, regional and local law enforcement agencies, at all professional levels. Build on its current online learning programme and planned TAHCLE implementation to improve knowledge and awareness of frontline police. Consider drawing on the Facing Facts Online training programme.

Recommendation 2: The prosecution service and the courts should consider adapting the police definition of hate crime to agree aligned ‘hate crime prosecution’ and ‘hate crime sentence’ definitions, to ensure that the full picture of hate crime can be captured and acted on across the criminal justice system. Taking account of the findings of the ongoing review of cases handled by the prosecution service, consider the training needs of prosecutors and the possibility of implementing the ODIHR prosecutor training and hate crime recording programmes.

Recommendation 3: Clarify the process for referral of hate crime cases directly to the court to ensure that the prosecution service is fully informed and able to contribute relevant information.

Recommendation 4: Explore the potential to deepen cooperation between public authorities and expert NGOs working at the national level with a track record of recording and support. This could include:

- Establishing a subgroup on public authority-NGO cooperation on hate crime recording and data collection.

- Co-developing a clear definition of ‘hate crimes’ and ‘hate incidents’ including which protected characteristics to monitor and how to address and record hate crimes and incidents based on ideology (See recommendation five below)

- Specifying the details of the data sharing mechanism proposed in the Ministry of Interior hate crime action plan

- Identifying opportunities for CSO input on police and prosecutor training

- Identifying capacity building opportunities for CSOs to: develop monitoring and practical and legal support work for underserved groups, including victims of disability hate crime

In implementing this recommendation, particular attention should be paid to ensuring the correct representation of expert NGOs that directly support victims of hate crime.

Recommendation 5: Facilitate discussion and agreement on a shared definition of ‘hate crime’. Agreement should be sought across all stakeholders on:

- which characteristics will be included in national recording and monitoring policy

- ensuring the separate recording and monitoring of hate crimes, hate speech and discrimination

- how to approach the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of cases involving hostility on the grounds of ‘ideology’ in line with international standards concept

- consider the need for legislation that includes a definition of hate crime

Draw on international norms and standards in this regard as set out in ODIHR’s Hate Crime Laws: a practical guide, ECRI policy recommendations and recently issued guidelines from the European Commission.

Recommendation 6: Review current capabilities of CSOs to effectively record hate crime and to support victims and communities; and, identify and implement actions to build the capacity of CSOs in this area. Work with Facing Facts Online to identify and meet training and learning needs on hate crime monitoring and recording.

Recommendation 7: Consider setting up a national CSO network, which aims to monitor all forms of hate crime, using a shared methodology that is aligned with national recording practices, support all victims and use data and information to advocate for better implementation of national policy. Seek funding to support this work. This could include developing clear indicators on bias, and also support with public funds, even for strategic litigation.

Recommendation 8: All training activities, as well as judicial procedures, should take into account the gender perspective. Discrimination and hatred often have a multiple or intersectional nature, so that women experience more complex or aggravated situations because they are women in these cases. The intersectional perspective should be considered in hate crimes.[40]

Recommendation 9: Although this research has focused on the police and criminal justice response to hate crimes, it is recommended that stakeholders consider steps towards investing in human rights education that fosters tolerance and respect for diversity in the education system and across the media.

Bibliography & Endnotes

High Level Group on Racism and Xenophobia (2018) ‘Guidance Note on the Practical Application of Council Framework Decision on Combating Certain forms and Expressions of Racism and Xenophobia by Means of Criminal Law’, Brussels: European Commission, available online at https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/ document.cfm?doc_id=55607, (accessed on 3 August, 2019)

Ministry of Interior (2019) ‘Action plan to Combat Hate Crimes for the Spanish Security Forces’, availabe online at http://www.interior.gob.es/ documents/642012/3479677/Plan+de+accion+ingles/222063a3-5505-4a06-b464-a4052c6a9b48, accessed on 10 November 2019.

Ministerio de Empleo y Seguridad Social (2014) ‘Protocolo de Actuación para las Fuerzas y Cuerpos de Seguridad para los Delitos de Odio y Conductas que Vulner-an las Normas Legales sobre Discriminación’, Available online at: http://www.mit-ramiss.gob.es/oberaxe/ficheros/documentos/ManualApoyoFormacionFFyCCSegu-ridadIdentificacionRegistroIncidentesRacistasXenofobos.pdf

No Hate Speech Movement Blog, ‘Violeta Friedman, Survivor and Fighter’, available online at http://blog.nohatespeechmovement.org/violeta-friedman-survivor-and-fighter

OBERAXE (2011) “Estrategia integral contra el racismo, la discriminación racial, la xenofobia y otras formas conexas de intolerancia. (Aprobada por el Consejo de Ministros el 4 de noviembre de 2011), availabe online at http://www.mitramiss. gob.es/oberaxe/es/publicaciones/documentos/documento_0076.htm, accessed on 1 November 2019

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (2009) ‘Hate Crime Laws, a practical guide’, Warsaw: ODIHR, available online at https://www.facingfacts.eu/ research/connecting-on-hate-crime/ (accessed on 3 August, 2019)

OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (2014), ‘ODIHR Key Observations’, available online at, http://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/ files/documents/Website/Key%20Observations/KeyObservations-20140417.pdf, (accessed on 3 August, 2019).

Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018) Lifecycle of a Hate Crime: Comparative Report. Dublin: ICCL p. 67.

Zempi, I (2017) ‘Calling for a Debate on Recording Violence Against Police Officers as a Hate Crime’, available online at https://internationalhatestudies.com/calling-for-a-debate-on-recording-violence-against-police-officers-as-a-hate-crime, (accessed on 3 August, 2019)

[1] As a general rule, Facing all the Facts uses the internationally acknowledged, OSCE-ODIHR definition of hate crime: ‘a criminal offence committed with a bias motive’

[2] The following countries were involved in this research: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom (England and Wales).

[3] In terms of its conceptual scope, the research focused on hate crime recording and data collection, and excluded a consideration of hate speech and discrimination. This was because there was a need to focus time and resources on developing the experimental aspects of the methodology such as the workshops and graphics. International and national norms, standards and practice on recording and collecting data on hate speech and discrimination are as detailed and complex as those relating to hate crime. Including these areas within the methodology risked an over-broad research focus that would have been unachievable in the available time.

[4] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a detailed description of the research theory and approach of the project.

[5] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a full description of the research methodology.

[6] See the Methodology section of the European Report for agenda and description of activities.

[7] This timeline includes national milestones relating to hate crime and hate crime recording and data collection in particular.

10] See Methodology section of the European Report for further detail

[11] Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018) Lifecycle of a Hate Crime: Comparative Report. Dublin: ICCL p. 67.

[12] The extent of this ‘disappearing’ varied across national contexts, and is detailed in national reports.

[14] Based on interviews with individual ‘change agents’ from across these perspectives during the research.

[15] For a full description of the main stakeholders included in national assessments, and how the self-assessment framework relates to the ‘systems map’, see the Methodology section of the European Report.

[16] ODIHR Key Observations, http://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/files/documents/Website/Key%20Observations/ KeyObservations-20140417.pdf; this methodology could also be incorporated in the framework of INFAHCT self-assessment, as described on pp. 22-23 here: https://www.osce.org/odihr/INFAHCT?download=true

[17] See Methodology section of the European Report for instructions.

[18] Ideas on to how to do this are proposed in the recommendations at the end of this report.

[19] Phrase used to describe Spain’s progress at Consultation Workshop

[20] Interviewee 1

[21] The Observatory is situated in General Secretariat for immigration, emigration, established by legal duty to monitor racism or xenophobic incidents.

[22] Interviewee 2

[23] Interviewee 2

[24] Interviewee 2

[25] Interviewee 2

[26] Interviewee 3

[27] Interviewee 4

[28] See the Connecting on Data Report for England and Wales

[29] Interviewee 4

[30] Interviewee 1

[31] See Article 22(4) of Spain Criminal Code (e.g. – https://www.legislationline.org/documents/id/15764)

[32] See for example – https://internationalhatestudies.com/calling-for-a-debate-on-recording-violence-against-police-officers-as-a-hate-crime/

[33] Interviewee 7

[34] See ODIHR (2009) and https://www.facingfacts.eu/research/connecting-on-hate-crime/

[35] See ‘Guidance Note on the Practical Application of Council Framework Decision on Combating Certain forms and Expressions of Racism and Xenophobia by Means of Criminal Law’, https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/just/document.cfm?doc_id=55607.

[36] including the European Commission, DG-JUSTICE, the EU Fundamental Rights Agency, the OSCE-ODIHR and the Council of Europe

[37] Interviewee 1

[38] Interviewee 2

[39] European Court of Human Rigths; Interviewee 3

[40] See for example https://www.gitanos.org/upload/60/04/Guide_on_intersectional_discrimination_FSG_31646_.pdf

About the author

Joanna Perry is an independent consultant, with many years of experience in working to improve understandings of and responses to hate crime. She has held roles across public authorities, NGOs and international organisations and teaches at Birkbeck College, University of London.

About the designer

Jonathan Brennan is an artist and freelance graphic designer, web developer, videograph and translator. His work can be viewed at www.aptalops.com and www.jonathanbrennanart.com

Many thanks to Valentín González for organising the national workshops and interviews and for his expert input into the final report. We would like to thank everyone who took part in our workshops and interviews for their invaluable contribution.

This report has been produced as part of the Facing all the Facts project which is funded by the European Union Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (JUST/2015/RRAC/ AG/TRAI/8997) with a consortium of 3 law enforcement and 6 civil society organisations across 8 countries.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme