Perry, J. (2019) Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Italy. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.

Download the full report in PDF here.

Introduction

If we are to understand hate crime,[1] support victims and reduce and prevent the problem, there are some basic questions that need to be answered:

How many hate crimes are taking place? Who are the people most affected? What is the impact? How good is the response from the police? Are cases getting investigated and prosecuted? Are the courts applying hate crime laws? Are victims getting access to safety, justice and the support they need?

While ‘official’ hate crime data, usually provided by police reports, are the most cited source for answers to these questions, they can only tell a small part of this complex story. Understanding what happens to cases as they are investigated, prosecuted and sentenced requires a shared approach and cooperation across government agencies and ministries with responsibilities in this area, however, the necessary mechanisms and partnerships are often not in place. Reports and information captured by civil society organisations (CSOs) can also provide crucial parts of the jigsaw, yet connection across public authority- civil society ‘divides’ is even more limited.

The Facing all the Facts project used interactive workshop methods, in-depth interviews, graphic design and desk research to understand and assess frameworks and actions that support hate crime reporting, recording and data collection across a ‘system’ of public authorities and CSOs.[2] Researchers adopted a participatory research methodology and worked directly with those at the centre of national efforts to improve hate crime reporting, recording and data collection to explore the hypothesis that stronger relationships across the hate crime reporting, recording and data collection system lead to better data and information about hate crime and therefore better outcomes for victims and communities.

What was found is that a range of factors are key to progress in this area, including the:

- strength and comprehensiveness of the international normative framework that influences national approaches to reporting, recording and data collection;

- technical capacity to actually record information and connect with other parts of the system to share and pass it on;

- existence of an underlying and inclusive policy framework at the national level;

- work of individual ‘change agents’ and the degree to which they are politically supported;

- skill and available resources of those civil society organisations that conduct recording, monitoring and advocacy.

The research also found that each national context presents a different picture, and none is fully comprehensive or balanced.

This national report aims to describe the context and current picture of hate crime reporting, recording and data collection in Italy and to present practical, achievable recommendations for improvement. It is hoped that national stakeholders can build on its findings to progress in this critically important piece of broader efforts to understand and effectively address the painful and stubborn problem of hate crime in Italy.

It is recommended that this report is read in conjunction with the European Report, which brings together themes from across the six national contexts, tells the stories of good practice and includes practical recommendations for improvements at the European level. Readers should also refer to the Methodology section of the European Report that sets out how the research was designed and carried out in detail.

How did we carry out this research?

The research stream of the Facing all the Facts project had three research questions:[3]

- What methods work to bring together public authorities (police, prosecutors, government ministries, the judiciary, etc.) and NGOs that work across all victim groups to:

- co-describe the current situation (what data do we have right now? where is hate crime happening? to whom?)

- co-diagnose gaps and issues (where are the gaps? who is least protected? what needs to be done?), and;

- co-prioritise actions for improvement (what are the most important things that need to be done now and in the future?).

- What actions, mechanisms and principles particularly support and what undermines public authority and NGO cooperation in hate crime recording and data collection?

- What motivates and supports those at the centre of efforts to improve national systems?

The project combined traditional research methods, such as interviews and desk research, with an innovative combination of methods drawn from participatory research and design research.[4]

The following activities were conducted:

- Liaised with relevant colleagues to complete an overview of current hate crime reporting, recording and data collection processes and actions at the national level, based on a pre-prepared template;[5]

- identified key people from key agencies, ministries and organisations at the national level to take part in a workshop to map gaps and opportunities for improving hate crime reporting, recording and data collection.[6] This took place in Rome on 6 June 2017.

- Arranged for in-depth interviews with five people who have been at the heart of efforts to improve reporting, recording and data collection at the national level to gain their insights into our research questions.

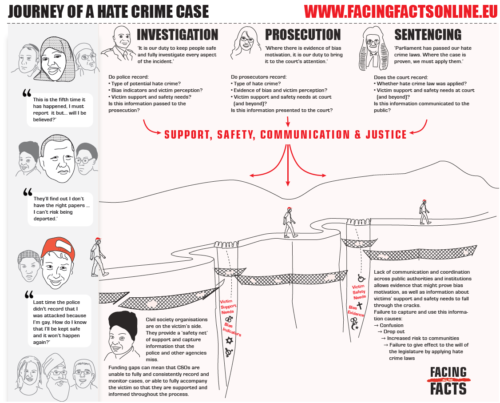

Following the first phase of the research, the lead researcher synthesised existing norms and standards on hate crime to create a self-assessment framework, which was used to develop national systems maps describing how hate crimes are registered, how data is collected and used and an assessment of the strength of individual relationships across the system. A graphic designer worked with researchers to create visual representations of the Journey of a Hate Crime Case (see below) and national Systems Maps (see ‘Mapping Italy’s Data Collection and Recording Systems’ below). Instead of using resources to launch the national report, it was decided that more connection and momentum would be generated at the national level, and a more accurate and meaningful final report would be produced, by directly consulting on the findings and recommendations during a second interactive workshop which was held in Rome, 24 May 2018.

During the final phase, the lead researcher and OSCAD reviewed the final reports and systems maps, seeking input and clarification with stakeholders, as needed. In addition, themes from this and other national reports were brought together and critically examined in the final, European Report.

The Journey of a hate crime

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[16]

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the 6 countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[16]

The Journey graphic conveys the shared knowledge and experience generated from this exercise. From the legal perspective, it confirms the core problem articulated by Schweppe, Haynes and Walters where, ‘rather than the hate element being communicated forward and impacting the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of the case, it is often “disappeared” or “filtered out” from the process.’[17],[18] It also conveys the complex set of experiences, duties, factors and stakeholders that come into play in efforts to evidence and map the victim experience through key points of reporting, recording and data collection. The police officer, prosecutor, judge and CSO support worker are shown as each being essential to capturing and acting on key information about the victim experience of hate, hostility and bias crime, and their safety and support needs. International norms and standards[19] are the basis for key questions about what information and data is and should be captured.

The reasons why victims do not engage with the police and the criminal justice process are conveyed along with the potential loneliness and confusion of those who do. The professional perspective and attitude of criminal justice professionals that are necessary for a successful journey are presented.[20] NGOs are shown as an essential, if fragile, ‘safety net’, which is a source of information and support to victims across the system, and plays a role in bringing evidence of bias motivation to the attention of the police and the prosecution service.

The Journey communicates the normative idea that hate crime recording and data collection starts with a victim reporting an incident, and should be followed by a case progressing through the set stages of investigation, prosecution and sentencing, determined by a national criminal justice process, during which crucial data about bias, safety and security should be captured, used and published by key stakeholders. The graphic also illustrates the reality that victims do not want to report, key information about bias indicators and evidence and victims’ safety and support needs is missed or falls through the cracks created by technical limitations, and institutional boundaries and incompatibilities. It is also clear that CSOs play a central yet under-valued and under-resourced role.

Click here to download the Journey in Italian.

Mapping Italy’s Data Collection and Recording Systems

The ‘linear’ criminal justice process presented in the Journey graphic is shaped by a broader system of connections and relationships that needs to be taken into account. Extensive work and continuous consultation produced a victim-focused framework and methodology, based on an explicit list of international norms and standards that seeks to support an inclusive and victim-focused assessment of the national situation, based on a concept of relationships. It integrates a consideration of evidence of CSO-public authority cooperation on hate crime recording and data collection as well as evidence relating to the quality of CSO efforts to directly record and monitor hate crimes against the communities they support and represent.[21] It aims to go beyond, yet complement existing approaches such as OSCE-ODIHR’s Key Observations framework and its INFAHCT Programme.[22] The systems map also serve as a tool support all stakeholders in a workshop or other interactive setting to co-describe current hate crime recording and data collection systems; co-diagnose its strengths and weaknesses and co-prioritise actions for improvement.[23]

The interactive ‘Systems map’ below is best viewed in full screen mode (click on the icon in the top right hand corner of the map).

Click on the ‘+’ icons for an evidence-based explanation of the colour-coded relationship, based on international norms and standards.

Or download ‘Self-assessment grid on hate crime recording and data collection, framed by international norms and standards – ITALY (PDF 278KB)‘

Commentary

The red lines between the main law enforcement and criminal justice agencies and their ministries illustrate the lack of an institutional, cross government framework on hate crime reporting, recording and data sharing. The information available to policy makers and practitioners is limited because there is no shared definition of hate crime, no technical connection across databases, and a lack of ability to record and extract data on the range of hate crime. Further, the fact that crimes based on bias towards LGBT+ people cannot be currently recorded by the police reflects a hierarchy of protection in Italy’s official hate crime recording policy (and law). While data recorded by law enforcement and OSCAD sheds important light on the current situation in Italy, the lack of data relating to the outcomes of prosecutions and sentencing decisions means that policy makers, affected communities and the Italian public are in the dark about the effectiveness of hate laws.

OSCAD has made significant progress in raising awareness about hate crime within the National Police and Carabinieri (the two Italian national police agencies that deal with preventing and combating hate crime) in the areas of: training to improve the detection and investigation of hate crimes, and liaising on specific cases to improve responses; establishing relationships with civil society organisations and UNAR on receiving hate crime reports and with IGOs on data sharing and capacity-building. There are signs that this hard work is having an impact: recorded hate crimes doubled from 2015-2017. Lunaria’s relatively robust and longstanding recording, monitoring and advocacy suggests that they would be an appropriate partner for deeper cooperation with law enforcement agencies and/or OSCAD.

The systems map shows a tendency for data to be made available to IGOs as opposed to being disseminated throughout the Italian public at the national level. In February 2018 the OSCAD webpage, hosted on the website of the Ministry of Interior, was revised to include public statistics on reports sent to OSCAD.[24] While planned for some time, participation in both the Facing all the Facts project and the subgroup on methodologies for recording and collecting data on hate crime contributed to this significant improvement in transparency. This suggests an important shift towards national stakeholders, also supported by international projects.

The lack of coordination across CSOs is also apparent and presents a missed opportunity to forge strategic relationships with public authorities and ministries for the benefit of victims of hate crime across the country. There is very little activity in the area of monitoring disability hate crime and anti-Muslim hate crime both by civil society and official bodies.

These issues could be addressed by introducing a coordinated approach, for example, in the form of a coordinating agency or an inter-agency ‘mechanism’ to monitor hate crime, involving those CSOs that are skilled and experienced in hate crime recording and data collection including COSPE, Lunaria, Arcigay and Rete Lanford, and by introducing monitoring definitions and protocols. These points are further explored in the recommendations.

National context

The technicalities of hate crime recording and data collection take place in a dynamic social, political and institutional context, which needs to be considered in efforts to identify key actions for improvement to Italy’s hate crime recording and data collection system. As set out in the timeline, public consciousness about hate crime is likely to have been shaped by many serious racist attacks across the country. Specific steps have been taken to ensure the courts can recognise crimes motivated by bias and hostility and important institutional developments have established expertise and connection. However, Italy’s progress on hate crime recording and data collection could be described as one of incremental change, albeit in the right direction. In a context of strong cooperation between elements of the Italian state, especially OSCAD, and civil society within a supportive international framework comprised of specific projects, and relevant policy developments, people at the centre of efforts have been ‘stretch[ing] boundaries….carefully’.[25] However, the systems map illustrates that this positive work is taking place in a strategic vacuum with no national framework that can support inter-institutional cooperation.

As other countries in Southern Europe, Italy is challenged by a recent influx of refugees and migrants and by the related apparent rise in anti-immigrant sentiment in the public and political spheres, sometimes manifesting as racism and racist crime. One interviewee remarked that the conversation has moved away from the general problem and impact of racism in Italy to ‘more emergency issues’ also negatively affecting multi-generation Italians with an ethnic minority background. The same interviewee asked, ‘what is the number that tells you that there is a problem?’[26] Underlying his question was a worry that even a high number of recorded crimes and media attention on recent killings of migrants might not shift public awareness to a broader concern about the impact of hate crimes on individuals, their families and society without the political will and implementation strategy to understand and address the problem. While our research found that there is great potential to strengthen and broaden existing cooperation and significantly improve hate crime recording and monitoring across the NGO and public authority spheres in Italy, these are limited actions that must be considered within significant broader societal and political challenges.

‘The context of police – CSO cooperation: different starting points, different missions… [yet] moving towards the victim

Several interviewees commented on the need to recognise the necessarily different starting points and thus different perspectives of those involved in hate crime recording and data collection. One police officer provided insight into the challenges of taking a different perspective on hate crime,

‘it is a little bit tough because you have to work from another point of view… you have to take more into consideration the perception of the victim…some of the complaints against police and some police complaints against equality bodies or NGOs [can be] because the two of them don’t know what exactly they do and what their mission is…they can’t have the same mission’.[27]

These differences in approach on hate crime recording were reflected during the first workshop, with CSO data and perspectives focusing on the experience and perception of the victim and public authorities focusing on more ‘objective’ information about the victim, offender demographics and potential crime type.

One interviewee felt that a commonly held belief within the police is that ‘solving problems’, rather than addressing more structural issues of discrimination, is central to their mission. This, she argued is a specific barrier to cooperation with organisations working on anti-discrimination. Accepting the importance of the police ‘problem-solving’ role, she pointed out that a shift in mindset is also needed, ‘we have to work [together], because in a society free from discrimination everybody gains, everybody lives better, and also police can do his job in a better way’.[28]

‘Making steps towards the victims’

Several interviewees provided positive examples of senior police taking the decision to engage with communities including:

- senior police initiating meetings in CSO premises instead of requiring CSO representatives to come to the police;

- inviting NGOs to co-design and co-train on hate crime;

- involving communities in sensitive and challenging discussions around policing refugee and migrant communities;

- keeping in mind that it is possible to hold very different positions in one area, yet cooperate and move forward in others;

- remembering to treat each other with respect. One CSO interviewee explained that a key element of effective cooperation is, ‘being recognised and respected as valid interlocutors’ . Conversely, she explained that being treated with disrespect by one member of an institution, can feel the same as not being respected by the institution itself.[29]

These positive examples indicate rich pockets of leadership and commitment, however, they take place in a context of limited strategic connection across public authority and CSO ‘divides’.

Building on the current context: ‘from the occasional to the institutional’

The most successful and developed connection between CSOs and public authorities is in the area of training where CSOs systematically contribute to OSCAD’s training seminars on hate crime. As one interviewee put it, ‘[with NGO involvement] we immediately noticed that the quality of our efforts increased very much’.[30]

However, overall, cooperation with the police was described as ‘sporadic’ and ‘at the discretion of the investigating officer’. During the first workshop in June 2017, the point was made by NGO representatives that ‘the victim opens up easily with CSOs, providing lots of data: synergy between CSOs and police forces is needed’. One interviewee commented that the positive interactions taking place between OSCAD and NGOs should progress from the ‘occasional to the institutional’.[31] However, this shift requires strategic decisions that better orientate all institutions and agencies towards better hate crime and data collection practice across the whole system.

There is evidence that the capacity and skills of CSOs would need to be significantly developed should public authorities seek to engage more strategically. During the workshop in June 2017, CSOs pointed out that there is a ‘problem of robust collection of [CSO] data to be shared with OSCAD and UNAR in order to support advocacy activities’. CSO recording methods were described by one experienced CSO as ‘descriptive’ and not ‘statistical’ and often based on media reports only.[32] As can be observed on the systems map, there are few examples of strong relationships between victims of hate crime and CSOs skilled in hate crime recording and support.

Research, interviews and feedback during the consultation phase offered two main reasons for this. First, there is a lack of resources. As a member of an organisation supporting LGBT+ communities pointed out, ‘We stopped recording. But why, not because it is not important, but the problem was that there were so many that we could no longer afford to go through the recording process and to offer help’.[33] Current funding offered through UNAR’s grant programmes was identified as too short term and over-focused on awareness-raising as opposed to systematic monitoring. As one contributor pointed out, ‘Systematic monitoring and data collection can hardly be financed through periodic and competitive call for proposals, if such activity is to become a continuous one’.[34]

Secondly, it was observed that the absence of an ‘official’ definition of hate crime had a negative effect on the quality of hate crime data produced by the Italian hate crime recording and data collection system overall, whether by public authorities or CSOs. Different bodies use varied and incompatible methods of recording and data collection, producing uncomparable data. As illustrated by the systems map, no data is systematically recorded or collected at the prosecution stage of hate crime cases, precluding conclusions about how well hate crime progress through the criminal justice process. Equally, there is evidence of discrepancies between the numbers of hate crimes and incidents recorded by CSOs and the number recorded by UNAR for its annual report to Parliament and to the Council of Ministers.[35] The argument was offered that until a common approach to defining hate crime is taken across the system, it is impossible to obtain reliable, comparable data from the investigation to prosecution and sentencing stages, also encompassing data and information from CSOs.

There are some examples of promising practice by CSOs. For example, LUNARIA’s recording and monitoring work is relatively robust and longstanding and might provide the basis for deeper cooperation between law enforcement in the area of hate crime recording and data collection and investigation practice. There are also aspects of practice that could be further explored in the cooperation between L’UCEI (Unione delle comunità ebraiche italiane) and law enforcement relating to the protection of Jewish communities.

It was pointed out by CSOs during the consultation meeting on 23 May 2018 that the issues involved in hate crime investigations can be complex and require strong cooperation between expert CSOs and law enforcement. One idea was to work together to produce specific guidelines relating to how to sensitively investigate crimes based on bias against LGBT+ people and other types of hate crimes.[36]

Culture [of] change?

Effective cooperation often involves an appreciation of cultural differences across public and civil society institutions. ‘Stretching boundaries….carefully’, is how

one interviewee described one of the most effective ways of achieving change in conservative and hierarchical institutions such as the police.[37]One example of ‘successful boundary stretching’ given was the process of securing the decision by senior management to continuously increase the length and quality of police trainings on discrimination delivered by OSCAD. Several interviewees pointed to the fact that while passion is essential, it needs to be ‘balanced with professionalism’.

While institutional change can be slow in some areas, key strategic decisions can significantly speed up the process. One interviewee observed that while positive change in the area of hate crime feels more like a marathon than a sprint, actions such as the establishment of OSCAD were a ‘great leap forward’.[38]

Another interviewee called OSCAD and UNAR the major ‘pillars’ in efforts to understand and address hate crime.[39] It is clear from the systems map that OSCAD has secured many of the necessary positive connections and communication flows that form the basis of an effective hate crime recording and data collection system.

Its innovative method of monitoring hate crime on the grounds of LGBTI, its actions to improve the granularity of information on other types of hate crime, its sustained focus on police training, and involving CSOs as partners are likely to be key influencing factors behind the steady increase in recorded hate crimes since 2015.[40]

Support for those at the centre of efforts to improve hate crime responses was also identified as being of central importance. For some the international working groups and initiatives, the European Commission’s High Level Working Group on Racism and Xenophobia and the subgroup on hate crime recording were key to securing the impetus to move forward on securing improvement to hate crime recording and training at the national level. Positive and productive interpersonal connection were as important. Several interviewees pointed to the significant support and professional boost they felt when meeting their counterparts from other countries at events organised by ODIHR, the FRA, the European Commission, and others. Finally, being treated with respect by institutions and organisations at the national level were reported to greatly support collaborative efforts.

Recording hate crimes against LGBTI people

The particular situation of information about hate crime against LGBTI people was raised by several interviewees. Recording hates crimes based on bias towards LGBTI people is challenging because these groups are not recognised in Italy’s hate crime legislation. For one interviewee, the journey towards recognising LGBTI people as a group targeted by hate crime is connected to broader civil rights struggles. As she put it, ‘It is difficult to say that a category of people is a target of offences if that very category is not even recognised from a legal point of view’.[41]

There has been progress. Legal recognition of same-sex partnerships has been in place since 2015 and OSCAD has been monitoring homophobic and transphobic crime since its inception in late 2010, in cooperation with the equality body UNAR. One outcome from the Connecting on Hate Crime Data workshop was an agreement in principle to seek cooperation with an LGBT organisation that plans to focus on hate crime recording.

An interviewee from an LGBTI organisation described an interesting attempt to ask the Italian courts to determine whether denying the genocide of LGBTI people by Nazi Germany would fall within the newly enacted legislation on ‘negationism’, which would provide some recognition of LGBTI bias in the broader Italian legal framework relating to ‘hate’.

Recommendations

This section builds upon recommendations from previous reports on hate crime, including Lunaria and the Jo Cox Commission. They are focused on improving hate crime recording through a cooperative approach between NGOs and public authorities.

Recommendation 1: Consider developing a definition of hate crime for monitoring purposes.

It was agreed at the consultation meeting in May 2018 that implementing a shared monitoring definition would improve the granularity of information relating to offences based on racism, religion, nationality, language and disability (currently covered by the law) as well as offences based on bias towards sexual orientation and gender identity currently not protected by the law. It could also be adopted by CSOs that record and monitor hate crime, thus developing a common basis for cooperation in this area. In seeking to move forward on the recommendations, stakeholders should draw on resources from FRA and ODIHR.[42]

Recommendation 2: Move towards a joined up approach to record and monitor hate crime across government ministries, public authorities and civil society organisations.

Several interviewees, as well as workshop participants expressed the view that a clearer understanding of the prevalence and nature of hate crime in Italy would be achieved with better coordination of hate crime recording and data collection across all organisations, both statutory and non-statutory. One interviewee pointed to the fact that ‘no one has the complete picture’ at the national level and that establishing a national coordinating body would help address this problem.[43] This view was supported by the workshop findings and conclusions.

The following overall recommendation was agreed in principle at the consultation workshop in May 2018, however, the specific model and way forward will need to be confirmed. The text below gives some ideas to consider.

Recommendation 3: Consider securing agreement across the relevant ministries and agencies to establish a framework that allows for regular meetings to discuss the current situation on hate crime reporting and recording and agree and monitor actions for improvement. In establishing this framework the following could be considered:

- implement a rotating chair whose role it would be to initiate and coordinate meeting agendas and, with the help of the secretariat (below), monitor the actions of member departments and agencies, including on hate crime recording and data collection. The chair would rotate across the main stakeholders working on the issue across the relevant government departments;

- appoint a competent body to act as the secretariat and to, inter alia, keep track of actions and agreements, ensure regular and effective meetings and communication. Consider OSCAD to perform the secretariat function in the first instance;

- ensure permanent representation from competent civil society organisations that conduct relevant monitoring based on a clear and effective methodology;

- draw on the resources of FRA/ODIHR hate crime recording and data collection workshops to maps gaps and opportunities and priorities for action at the national level.

Recommendation 4: Agree a framework for cooperation with competent CSOs on hate crime recording and data collection. This could include working towards a memorandum of understanding (MoU) for data sharing

Recommendation 5: development of simple, ‘pocket sized’ guidance for police on bias indicators. There is a low awareness about hate crime within the Italian police. Workstream 2 of the Facing all the Facts Programme is dedicated to developing online learning for frontline police to raise awareness and build knowledge and skills in this area and OSCAD is developing online learning tailored to Italian law enforcement agencies. The proposed leaflet would complement this approach and serve as a simple tool to support everyday responses and investigations.

Recommendation 6: Improve transparency and visibility of official data. The recent move to improve the visibility of OSCAD data could be built upon to publish all

available data on hate crime from across the system. Italian officials could consider drawing on other approaches in the EU for inspiration in this regard (e.g. the Netherlands).

Recommendation 7: Review and revise current funding and support programmes aimed at CSOs that conduct hate crime recording, monitoring and victim support.

Bibliography & Endnotes

The “Jo Cox” Committee on hate, intolerance, xenophobia and racism (2017) ‘The Pyramid of Hate in Italy, The “Jo Cox” Committee on hate, intolerance, xenophobia and racism, final report’, available at http://website-pace.net/ documents/19879/3373777/20170825-HatePyramid-EN.pdf (accessed on 22 May, 2019).

European Union Fundamental Rights Agency (2018) ‘Hate Crime Recording and Data Collection Practices Across the EU’, FRA:Vienna, available at https://fra.europa.eu/ sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2018-hate-crime-recording_en.pdf, (Accessed on 23 May 2019).

Perry, Perry Kessaris (forthcoming) ‘Participatory and designerly strategies for sociolegal research impact: Lessons from research aimed at making hate crime visible’

Lunaria (2019) ‘Between Removal and Emphasization: Racism in Italy in 2018’, available at http://www.cronachediordinariorazzismo.org/wp-content/uploads/ FOCUS1_2019_RacisminItalyin2018.pdf (Accessed on 23 May,2019).

Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018) Lifecycle of a Hate Crime: Comparative Report. Dublin: ICCL

[1] As a general rule, Facing all the Facts uses the internationally acknowledged, OSCE-ODIHR definition of hate crime: ‘a criminal offence committed with a bias motive’

[2] The following countries were involved in this research: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom (England and Wales).

[3] In terms of its conceptual scope, the research focused on hate crime recording and data collection, and excluded a consideration of hate speech and discrimination. This was because there was a need to focus time and resources on developing the experimental aspects of the methodology such as the workshops and graphics. International and national norms, standards and practice on recording and collecting data on hate speech and discrimination are as detailed and complex as those relating to hate crime. Including these areas within the methodology risked an over-broad research focus that would have been unachievable in the available time.

[4] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a detailed description of the research theory and approach of the project.

[5] See Methodology section of the European Report for a full description of the research methodology

[6] See Methodology section of the European Report for agenda and description of activities

[7] The timeline includes:

- hate crimes that reached the national consciousness, often because of the impact on the family and communities or because of a poor response to the incident by the authorities; and,

- key developments on hate crime data such as the publication of an important report, national hate crime strategy or action plan, the setting up of a relevant institution or the first meeting of national group set up to actively address the issues.

[16] See Methodology section of the European Report for further detail

[17] Schweppe, J. Haynes, A. and Walters M (2018) Lifecycle of a Hate Crime: Comparative Report. Dublin: ICCL p. 67.

[18] The extent of this ‘disappearing’ varied across national contexts, and is detailed in national reports.

[19] See appendix XX

[20] Based on interviews with individual ‘change agents’ from across these perspectives during the research.

[21] For a full description of the main stakeholders included in national assessments, and how the self-assessment framework relates to the ‘systems map’, see the Methodology section of the European Report.

[22] ODIHR Key Observations, http://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/files/documents/Website/Key%20Observations/ KeyObservations-20140417.pdf; this methodology could also be incorporated in the framework of INFAHCT self-assessment, as described on pp. 22-23 here: https://www.osce.org/odihr/INFAHCT?download=true

[23] See Methodology section of the European Report for instructions.

[24] http://www.interno.gov.it/it/ministero/osservatori/osservatorio-sicurezza-contro-atti-discriminatori-oscad

[25] Interviewee 3

[26] Interviewee 6

[27] Interviewee 1

[28] Interviewee 1

[29] Interviewee 5

[30] Interviewee 3

[31] Interviewee 5

[32] Interviewee 4

[33] Interviewee 5

[34] Interviewee 4

[35] In accordance with art. 7-F Legislative Decree nr 215/2003

[36] This approach is supported by a recent FRA report, which identified four main ways that CSOs and the police can cooperate in the area of hate crime recording and data collection: Exchanging data and information; Working together to uncover the ‘dark figure’ of hate crime ; Cooperating on the development of instructions, guidance or training on recording hate crime, including exchanging expertise to develop, refine and revise bias indicators ; Establishing working groups on how to improve the recording of hate crime. See FRA (2018)

[37] Interviewee 3

[38] Interviewee 2

[39] Interviewee 1

[40] According to OSCE data, recorded hate crimes have increased from 555 to 1048 between 2015-2017.

[41] Interviewee 5

[42] See Joint workshops offered by FRA and ODIHR as well as ODIHR’s INFAHCT programme, https://www.osce.org/odihr/INFAHCT

[43] Interviewee 3

About the author

Joanna Perry is an independent consultant, with many years of experience in working to improve understandings of and responses to hate crime. She has held roles across public authorities, NGOs and international organisations and teaches at Birkbeck College, University of London.

About the designer

Jonathan Brennan is an artist and freelance graphic designer, web developer, videographer and translator. His work can be viewed at www.aptalops.com and www.jonathanbrennanart.com

Many thanks to Stefano Chirico, Lucia Gori and Ilaria Esposito for their untiring efforts and support in organising the national workshops and interviews and in producing the final report. Thank you for always going far above and beyond reasonable expectations! Thank you also to Rita Novello and Carla Serpenti for fantastic interpreting during the workshops and interviews, and their help and ‘eagle eyes’ when translating the final report.

We would like to thank everyone who took part in our workshops and interviews for their invaluable contribution.

This report has been produced as part of the ‘Facing all the Facts’ project which is funded by the European Union Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme (JUST/2015/RRAC/ AG/TRAI/8997) with a consortium of 3 law enforcement and 6 civil society organisations across 8 countries.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme