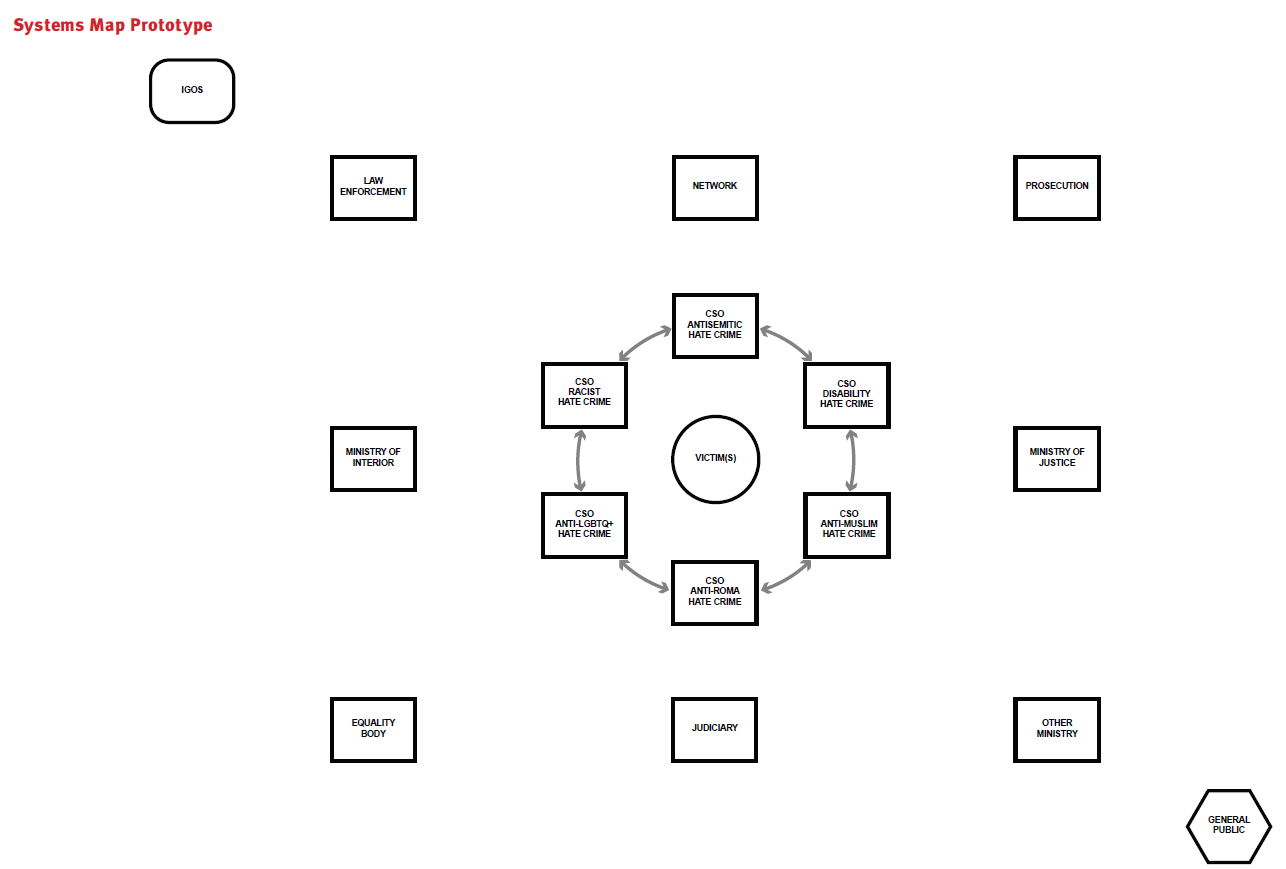

The ‘hate crime recording and reporting system’

(cite as: Perry, J. (2019) ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Europe’. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.)

The ‘linear’ criminal justice process presented in the Journey concept, explained in the previous section is shaped by a broader system of connections and relationships.[1] Extensive work and continuous consultation produced a victim-focused self-assessment framework that was used to describe the core relationships that comprise this system. The resulting Systems approach was tested as a tool to support all stakeholders in a workshop or other interactive setting to co-describe current hate crime recording and data collection systems; co-diagnose its strengths and weaknesses and co-prioritise actions for improvement.[2]

In preparing the published ‘systems maps’, the following evidence was considered:

- The strength of national policies and technical frameworks, and the effectiveness of related action

- The degree of cooperation across all actors in the ‘system’ on hate crime recording and data collection

- The quality of CSO efforts to directly record and monitor hate crimes against the communities they support and represent[3]

The Facing all the Facts method aims to go beyond, yet complement existing approaches such as OSCE-ODIHR’s Key Observations framework and its INFAHCT Programme.[4] In this sense, our approach was somewhat experimental, and national ‘maps’ are still a work in progress that it is hoped will be continued by national stakeholders. The final recommendations consider specific steps that might be taken to better integrate this ‘systems’ approach into ongoing reporting and recording capacity building activities. This section considers emerging themes from analysis of the six national maps that were developed from our research.

This graphic shows the most common stakeholders in most national hate crime reporting, recording and data collection ‘systems’. The Facing all the Facts research activities created six national ‘systems maps’, describing the strengths and weaknesses across stakeholders, based on evidence from desk-based research, interviews and workshops. See the Methodology Section for a full description and critical analysis of this approach. See the national reports for individual country systems maps.

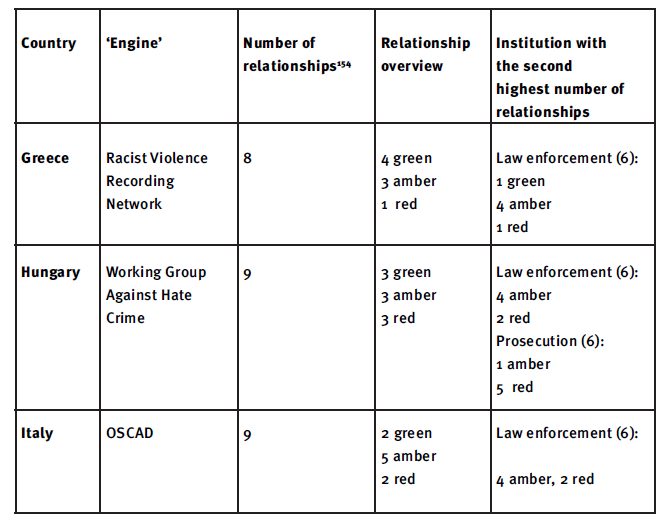

‘Engines’ for change

Several countries had what could be described as an ‘engine’ that consistently – and measurably – generates positive progress in hate crime reporting and recording at the national level. As seen in the table below, the ‘engines’ impact was evidenced by the fact that they had the highest overall number of relationships, and, within this, the highest number of green relationships across the ‘system’. These ‘engines’ work in different ways and could be ‘driven’ by a public authority, CSO or, a hybrid of the two. They tend to be proactive, reaching across institutional boundaries to organise trainings, push for guidelines on recording, investigation and prosecution, for example, and engaging with IGOs for capacity building activities. These engines were identified in three countries: Greece, Hungary and Italy.

Table of ‘engine’ relationships:

This table gives an overview of the number and strength of relationships of ‘change engines’ in Greece, Hungary and Italy. The number of relationships refers to where there is evidence that the change engine has a connection with another part of the system (e.g the police or a government ministry). The strength of that relationships is rated as ‘green’, ‘amber’ or ‘red’. To summarise, ‘green’ means that the relationships is ‘good’; that there is evidence of an effective framework and action on recording and reporting, with room for improvement. ‘amber’ means that the relationship is ‘adequate’, with evidence of a limited framework and action. ‘red’ means that there is a ‘poor’ relationship and evidence of inadequate framework and action. There is a detailed explanation of the underpinning self-assessment framework.

The Racist Violence Recording Network, Greece[6]

Established in 2011, The Racist Violence Recording Network (the Network) was the first to reveal the nature of contemporary, targeted violence in Greece. [7] The Network’s 40+ members follow a shared recording methodology, which is based on direct testimony from victims. In this way, the Network has established a broad reach and ensured that members are ‘on the same page’ when recording incidents, while also being free to fulfil their own diverse missions to meet the medical, legal, housing and even nutritional needs of their users from across diverse communities.

As time progressed, the Network was recognised by public authorities, IGOs, the media and politicians alike as the main source of information for racist, homophobic and transphobic attacks in Greece. Institutional backing from UNHCR and the National Commission for Human Rights was essential to secure the legitimacy of its data.[8] The Network’s data and information contributed to the decision to set up specific police units, to conduct specialist training, and to the revision of national hate crime laws. The coordinator of the Network sits on the recently established body set up to oversee the implementation of the ‘Agreement on Inter-agency cooperation on addressing racist crimes in Greece’, which includes specific commitments to improve hate crime reporting, recording and data collection across the system.[9]

The Network’s influence on national hate crime reporting, recording and data collection practice is partly evidenced by the significant increase in the number of hate crimes registered by the State following the publication of the Network’s first annual report. In 2012, one hate crime was reported by the Greek authorities to ODIHR for inclusion in their annual hate crime report. In 2013, the year after the Network’s first full annual report, this number jumped to 109 hate crimes.[10] One interviewee emphasised the broader context,

‘You cannot say that it was the network that changed everything. Because if it is so easy, you wouldn’t need a network, because at the same time, we shouldn’t be pessimistic, because it is all things together that led to the change, not one thing or the other thing’.[11]

The Network’s regular publishing of hate crime data through its annual reports and press releases about specific cases has strengthened its visibility with the general public. Its longstanding good practice and national influence has led to requests to share its practice on the international stage.

The Working Group Against Hate Crime, Hungary[12]

The Working Group Against Hate Crime in Hungary was set up by a small number of CSOs in January 2012.[13] Its work includes giving opinions on draft laws and how to improve state responses, and developing and implementing curricula and training for police and other public authorities. Its members offer legal representation and overall, the working group endeavours to, ‘foster good professional relations with NGOs, the police, the public prosecutor’s office, other authorities and the judiciary’. The members of the working group record cases using their own case management system, usually with a flag for hate crimes. Members of the group use a joint database onto which cases are uploaded.[14]

The Working Group draws on this evidence as well as its in-depth reports to evidence the problem of hate crime and failings in the state’s efforts to address it. For example, its report, ‘24 Cases’ provide rich detail about problems at the identification and investigation stages in specific cases.[15] This and other monitoring work formed the basis of cooperation with the police in several areas. In 2015, following the publication of the ‘24 Cases’ report the WGAHC, the police and the prosecution service agreed that a concise list of indicators to help the identification of hate crimes would be a useful tool to address the shortcomings identified in the report. The WGAHC took the lead and drafted a list of indicators based on a careful consideration of various international examples. In January 2016, the list was circulated for comments among police, prosecution, judiciary, victim support services, lawyers and academic institutions.[16] The draft was revised and shared with the police in 2016. It was agreed to make a shorter, two page version of the list[17] and a four page version[18] with a third column providing examples to the indicators.[19] The lists were finalized, disseminated to stakeholders and published in November 2016 on the Working Group’s website. The police agreed to use the materials in trainings and upload it to the intranet of the police, which was done in March 2018.

Again, the WGAHC took the lead in preparing a manual that harmonizes investigative requirements with data protection considerations, and a list of suggested interview questions to use for such sensitive matters. The manual was then approved by the National Authority for Data Protection and Freedom of Information, and was discussed at a conference co-organized by the Working Group, the National

University for Public Service and the hate crimes network in November 2017. The manual will be published after necessary revisions.

The Network in Greece and the Working Group in Hungary took different approaches to documenting hate crime and working across the ‘system’ to address it, both of which have been effective, in challenging political circumstances.

The Observatory for Security against Acts of Discrimination (OSCAD), Department of Public Security, Ministry of the Interior, Italy

Government ministries can also house the ‘engine’ of change. OSCAD is a multi-agency body formed by the Italian National Police and the Carabinieri, housed within the Department of Public Security at the Ministry of the Interior. OSCAD has implemented a national police training programme, based on ODHIR’s Training Against Hate Crime for Law Enforcement (TAHCLE) methodology, with systematic input from CSOs; set up a system to refer hate crime cases to relevant law enforcement personnel; established a specific way to receive reports and record incidents of hate crime against LGBT+ communities, which are not currently covered by Italian law; and established a memorandum of understanding with Italy’s equality body (UNAR) to ensure that it hate crime reports to UNAR are referred back to OSCAD. OSCAD also cooperates fully with IGOs on information-sharing and capacity-building. There are signs that this hard work is having an impact: recorded hate crimes doubled from 2015-2017.

Running out of road

The systems maps also show that without a strategic framework that is sparked and supported by political will, these engines can only ‘drive’ so far. For example, Italy’s systems map and country report illustrate the stark reality that without a framework, the strongest relationships start, and mainly end, with OSCAD.[20] Different bodies use varied and incompatible methods of recording and data collection, producing un-comparable data that cannot be traced through the criminal justice system and process. There are no cross government or inter-institutional agreements on hate crime in Hungary, producing the same problem of data incompatibility. The positive cooperation that has been developed over years between the police and the Working Group Against Hate Crime in particular, could end at any time without particular reason or explanation. Ireland has no national legal or policy framework on hate crime and, while there has been excellent work by researchers and CSOs to evidence the problem of hate crime and recent positive leadership by the police, there is no obvious ‘engine of change’.

The next section considers Spain and England and Wales where systems have evolved to develop a cross-government, inter-agency and strategic approach to improving recording and increasing reporting.

Building a hate crime reporting and recording infrastructure: taking a strategic approach

Spain’s progress in efforts to understand and address hate crime has taken ‘a big jump forward’ in the last 4-5 years.[21] One source of evidence of this ‘jump’ is the more than five-fold increase in the number of recorded hate crimes since 2013. This progress was sparked by the implementation of its National Strategy against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and other forms of Intolerance, which is overseen by an actively coordinated inter-institutional steering committee, and underpinned by a cross government memorandum. The Committee or inter-ministerial ‘engine’ includes representatives from across government departments and criminal justice agencies, as well as CSOs that are active in monitoring cases and supporting victims of hate crime. The key ministries lead and resource different elements of the strategy. For example, the Ministry of Health leads on anti-LGBTI hate crime while the Ministry of Justice leads on hate crimes based on hostility towards religious identity. The group has a rotating chair, with its members taking turns at the helm, and specific subgroups monitoring progress. The secretariat for the group is provided by the Observatory Against Racism and Xenophobia (OBERAXE),[22] which organises meetings, coordinates agendas and follows up on agreed actions.

The group focuses on four areas, delivered and monitored by four working sub-groups:

- Hate speech;

- The analysis of sentences applied by the court;

- Statistics, including hate crime recording and data collection; and,

- Training

In relation to the subgroup on hate crime recording and data collection, one interviewee explained an overarching goal as, ‘Trying to get a description of the situation in Spain… So first [we need] to know what the situation is and how we can improve and then we will also be able to evaluate whether we have made progress.’[23]

In addition to Spain’s overall strategic approach, individual agencies and ministries are taking focused action. For example, the National Office on Hate Crime within the Ministry of Interior has built on its first Action Protocol and is in the early stages of implementing its Police Action Plan to Combat Hate Crimes including specific, fully costed commitments and a clear structure of accountability.

Findings from England and Wales suggest that a long term strategic focus on increasing reporting and improving recording leads to data of sufficient quality to identify trends in prevalence, reporting and recording and where the most entrenched challenges and barriers lie. The first hate crime action plan was published in England and Wales in 2009 and refreshed in 2012, 2016 and 2018. The action plan’s implementation is overseen by an inter-ministerial group, which delegates actions to an operational partnership comprised of police, prosecution and other criminal justice representatives. The governance and delivery groups are scrutinised and informed by an Independent Advisory Group comprised of representatives from CSOs across targeted communities. Police have been recording incidents of racist crime since 1986; the prosecution service have recorded the number and outcomes of race and religiously aggravated hate crime prosecutions since 2001; and the police and prosecution service agreed a joint definition of hate crime across the five monitored strands in 2008. Questions about people’s experiences of racist crime have been included in national victimisation surveys since 1988. Data on hate crime victimisation across the five monitored strands have been published since 2013. Police-recorded hate crime has increased by 123% since 2012/13, signalling increased reporting and improved recording. Data has been used to powerfully illustrate the ‘justice gap’ faced by all victims of hate crime and for some groups in particular.[24]

In addition, England and Wales is the only country in the study where police-CSO information-sharing agreements have been agreed, strengthening specific relationships in the system and taking cooperation to another level, providing an opportunity for institutional change, sparked by the ‘engine’ of this ‘hybrid’ network.[25]

Greece has just signed an inter-institutional agreement, overseen by steering group, which includes the Racist Violence Recording Network in its membership. If properly implemented, will support better reporting, recording and data collection.[26]

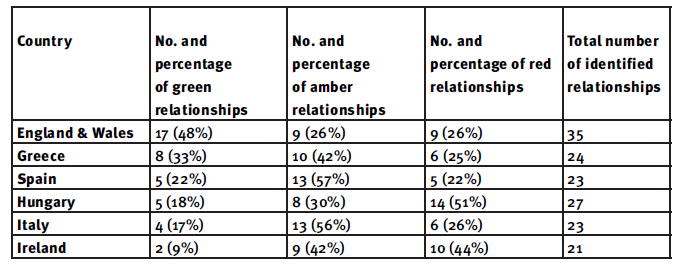

Overview of the number and percentage of green, amber and red relationships

Those countries with strategic frameworks have a higher percentage of green relationships across the system (Spain and UK). Greece also has a relatively high percentage of green relationships. This might partly be as a result of the long term efforts of the Racist Violence Recording Network and possibly because the government is in the early stages of embedding a strategic framework. Those countries that do not have a strategic approach have the lowest percentage of green relationships (Hungary, Italy and Ireland).

This brief analysis indicates that national systems are strengthened by change engines and by embedded strategic frameworks. This suggests that ways to effectively support change engines in diverse and challenging contexts should be further explored and that strategic frameworks that aim to increase reporting and improve recording should be explicitly encouraged. Again, CSOs are playing a central role in national efforts, one which could be better recognised in international norms, standards and capacity-building activities.

The role of law enforcement

Apart from the ‘engines of change’, as a national stakeholder, the police were the most likely to have the strongest relationships in the system, and the judiciary, the weakest. This partly reflects the ‘frontline’ position of the police in terms of receiving reports of hate crime from victims as opposed to the more ‘independent’ and removed position of the judiciary, as well as the fact that only a small proportion of any crime, including hate crime, is likely to progress to the sentencing stage. However, this also reflects the fact that most judicial authorities or courts systems do not have the facility to record information about whether hate crime laws were considered or applied at the sentencing stage. Nor do they have regular training on identifying and understanding hate crime in contemporary contexts. Other work has shown how failing to apply or to record the application of hate crime laws significantly undermines the implementation of the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia.[27]

Law enforcement are also likely to have better technical capacity and skills to record hate crime data and information than their key partners. The lack of capability on the other ‘side’ weakens law enforcement’s relationships across the system. For example, while law enforcement in Ireland and Spain are able to record a range of information and data about hate crimes there is little to ‘connect with’ on the prosecution and judicial side of the relationship, meaning data is ‘stuck’ in the early stages of the process. In the case of Ireland, this included relationships within institutions where the hate crime ‘flag’ cannot be passed to the prosecution stage, even when the police themselves are conducting the prosecution. In Hungary, while the prosecution services shares a recording system with the police during the investigation stage, should the case progress to court, a different, unlinked, much more limited system is used. The police also usually had the best relationships with civil society organisations, however, only England and Wales had a systematic framework for data sharing.

From the CSO perspective, it appears that the CSO ‘network approach’ led to the strongest relationships across the system. Hungary and Greece both have active, skilled and influential hate crime recording networks that work across affected groups to engage with the police and other agencies to improve recording and responses. However, there are still challenges such as inconsistent recording methodologies, lack of resources, and challenging political contexts, which affected CSOs’ ability to form and strengthen relationships. These issues are explored in more detail later in this report.

In the UK, reports by the police and prosecution inspection bodies are a key source of information and insight into gaps in police recording and liaison with the prosecution service. These bodies inspect police and prosecution services against their own standards and policies and so provide a very useful assessment of the strengths and gaps in the system.

Unequal protection?

In every context, there are communities that are relatively under-served in recording and response efforts. For example, no countries effectively monitor disability hate crime from the official or the CSO perspective.

This is partly because there is no international legal framework directing Member States to recognise bias motivations other than racism and xenophobia. However, it is also a function of the level of investment, skill and knowledge of CSOs in this area. For example, no country had CSOs that were actively recording and monitoring disability hate crime at the national level. With the exception of Spain, there was also very low activity on recording and monitoring anti-Roma hate crime across the system.

As pointed out by Whine (2019), FRA research has uncovered a hierarchy in how seriously criminal justice professionals view specific types of hate crime. While 68% perceived racism and xenophobia as a very or fairly serious problem, only 23% of professionals viewed hate crime against persons with disabilities to be very or fairly serious, ‘these results suggest weaknesses in perception and understanding due to experience, or lack of it. If the professionals did not perceive hate crimes against disabled people to be serious it may be because disability hate crimes have received less attention than hate crimes against other categories’.[28]

For one interviewee from the public authority perspective this patchy coverage raised questions about whether a ‘one size fits all’ approach to building capacity and relationships is the most effective. Explaining why specific government funding was made available to improve CSO recording, reporting and support work with victims of anti-Muslim hate crime, the interviewee reflected ‘equality isn’t about doing the same things…it is about getting the same outcome of justice and safety.’[29]

The credibility of official data

Efforts to improve reporting and recording take place in the face of problems in crime recording in general and hate crime recording in particular. For example, in 2014 the police inspectorate for England and Wales found that overall crime was under-recorded by 19%.[30] Another inspection found that police missed the opportunity to record an incident as a hate crime in 11 out of the 40 cases they reviewed.[31] The Central Statistics Authority in Ireland publishes police crime data ‘under reservation’ due to ongoing concerns about its reliability.[32] Anecdotal evidence in other contexts suggests similar problems with police-recorded crime. As one interviewee pointed out, ‘Interestingly in [our country], crime statistics are [of] very bad quality but they are taken quite seriously.’[33]

Claims that police and prosecution data are the only acceptable ‘official’ information on hate crime should be understood in the context of evidenced problems with the credibility of crime statistics in general. The role of inspectorates and other bodies should be explored as a constructive approach that inspects public authorities against their own crime recording standards to uncover problems and point to workable solutions in this area.

Further, as pointed out by the main IGOs working in the area, national leadership needs to be seen to welcome the significant increase in recorded crimes that is the best source of evidence that hate crime reporting, recording and data collection policy is actually working.[34] In addition, a key source of information about the real prevalence of hate crime is national crime surveys that include measures on hate crime. However, out of the 6 participating countries in this research, only England and Wales conduct such a survey.[35]

The influence of IGOs on national hate crime systems

Relatively strong relationships between national authorities and IGOs is one of the most obvious findings from our analysis. For example, national ministries, or agencies such as law enforcement, regularly share information with IGOs in response to regular and ad-hoc requests. IGOs regularly invite ministry representatives to regular and ad-hoc meetings on hate crime recording and data collection. National ministries request assistance from IGOs for national capacity-building activities on police and other training. As we saw above, the relatively comprehensive framework of norms and standards supports this range of cooperation and connection.[36]

The influence of IGOs was seen by interviewees as mainly positive and constructive, keeping the issue on the agenda, providing spaces for connection at the European level and funding essential work. However, there is evidence that the motivation to compile and share hate crime data can stem from a desire to manage international reputations as opposed to the motivation to understand and address hate crime as a problem of national concern. For example, while data is regularly shared in response to numerous requests from IGOs, the same data is often not easily accessible to the public. In one workshop, a participant explained that she searches IGO websites to find out what is happening in her country in the area of hate crime because there is no easily accessible point of information at the national level.

The impact of international standards, efforts and activities at the national level was clear from the interviews. One interviewee highlighted two key benefits of international engagement. Firstly, elements of national social progress can be traced to its international obligations, such as the setting up of European anti-discrimination frameworks. Secondly, they also provide important support for change agents working at the national level, commenting that their existence and their outputs on hate crime and other human rights issues mean, ‘that on some level, you are not alone’.[37]

In light of the general international obligation to publish available hate crime data, Italy, Greece and Ireland stakeholders participating in the Facing all the Facts project supported the proposal to publish at least that data and information that is already published on IGO platforms.[38] A welcome impact of this research is that data that was not previously in the public domain is now (or will be).

Another interviewee commented,

‘one of the things which is usually very helpful for us is the EU and the international organisations…. EU legislation helps very much to make progress in our own country, so we need to adapt it to our own circumstances but this is usually very helpful.’[39]

One interviewee identified the impact of attending international meetings to be of great strategic importance for their institution, ‘The big step that [we] took forward was when we opened to the international environment.’[40]

Another interviewee acknowledged the influence of international norms, standards and capacity-building activities on the national context, while also pointing out that by engaging more closely with work at the national level, IGOs have themselves learned about national ‘realities’:

‘International organisations have set the standards for the Member States, they exercise pressure and have a supervisory role. They also provide technical assistance, organise seminars, facilitate the exchange of views with police from other countries. Their role is decisive. They put pressure on Member States to take the necessary measures. In recent years there is more understanding of the problems [we are] facing. Being in touch with the [national] reality, [IGOs] can see our possibilities.’[41]

The work of IGOs was also perceived to be important by CSOs, particularly the Commission’s funding programmes and FRA’s national surveys. However, the view was expressed that IGOs should offer more critical analysis of the data provided by public authorities and give more value to CSO data. As explained by one interviewee,

‘IGOs need to put value on civil society and non-governmental data on hate crime and research. They need to be more critical of state data. They need to demonstrate the gaps more starkly between state data and non-state data.’[42]

Several interviewees highlighted limits to the influence of international scrutiny. For example, when talking of the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, two interviewees pointed to the need for the Committee to have more ‘bite’ and to be able to do more than simply ensure that countries ‘take note’. One interviewee commended the approach of CERD and its shadow reporting system, suggesting that the European Union institutions consider a similar procedure.[43]

It is unclear how IGOs confirm the validity of national authority reports. For example, where public authorities make assertions about police training or guidance, IGOs should consider requiring Member States to provide evidence for their claims including copies of police or prosecutor guidelines, evidence of training, etc. IGOs should routinely and specifically address the tendency of MS to report to international agencies and not to prepare transparent information for national stakeholders and taxpayers. If the data submitted to IGOs isn’t in the public domain, IGO’s should strongly encourage MS to make it available in the national language.[44] Taking these steps could improve the public’s awareness of how national authorities understand the problem of hate crime and what they are doing about it.

There was some frustration about regular requests by IGOs to share examples of ‘good practice’ rather than supporting the good practice that is ongoing, including through better targeted funding and based on consultation with existing expert CSOs on the ground. As one CSO interviewee explained,

‘As if it were [good] practice that we were missing, we need the space to do the right thing…No, don’t fund another observatory for hate speech. Not that it isn’t important…I have other fish to fry first. We are struggling to find a way to fund escort and support services for hate crime victims’.[45]

Another interviewee contrasted the usual approach of sharing good practice with the idea of ‘shar[ing] failures, and then you know what to avoid’.[56]

IGOs have a central role to play in the ‘migration’ of the hate crime concept from the international to the national context and to support and constructively work across national stakeholders that are responsible for ‘operationalising’ norms and standards on reporting, recording and data collection IGOs can also learn from innovative national and local practice which translates (sometimes literally) the hate crime concept into effective approaches that are relevant to the national context and which can, in turn, positively influence international norms and standards.

It is important to bear in mind that our analysis of hate crime reporting and recording frameworks and actions was very focused on the role of the police and criminal justice agencies and the investigation, prosecution and sentencing process. More work is needed to evaluate what is being done to gather and act on hate crime data in other spheres such as housing and education.

« FINDINGS III BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS FINDINGS V »

[1] See the Methodology section for feedback from workshop participants on the ‘journey of a hate crime case’ and ‘systems mapping’ workshops.

[2] For a full consideration of the strengths, risks and weaknesses of this approach, see the Methodology section. Also see methodology section for a full ‘how to’ description of these workshops.

[3] For a full description of the main stakeholders included in national assessments, and how the self-assessment framework relates to the ‘systems map’, see the Methodology section.

[4] ODIHR Key Observations (n.d.); OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) (2018a, 29 August).

[5] The number of relationships illustrates the effort invested in inter-institutional connection. Some relationships will be red because there is no ‘framework’ or ‘action’ from the other ‘side’. However, ‘engines’ are also more likely to have more ‘green’ relationships than other bodies

[6] See ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Greece’ report.

[7] Racist Violence Recording Network (2019).

[8] Conceptualising racist violence in Greece as an issue of refugee protection allowed UNHCR to take a leading role and to commit resources to a service that didn’t discriminate on the grounds of migration or legal status. This is a model that should be considered by other UNHCR Offices.

[9] Agreement on inter-agency co-operation on addressing racist crimes in Greece (2018, 6 June).

[10] See OSCE/ODIHR Tolerance and Non-Discrimination Department (2019).

[11] Interviewee two, Greece.

[12] Working Group Against Hate Crime (GYEM) (2019a).

[13] Amnesty International Hungary (2019), Háttér Társaság (2019) Hungarian Helsinki Committee (2019), Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (TASZ) (2018).

[14] Descriptions of cases that the organizations handle are made public at Working Group Against Hate Crime (GYEM) (2019b).

[15] See Working Group Against Hate Crime (GYEM) (2014a, 2014b).

[16] The draft was send to 174 individuals/institutions. Feedback was received from 59 organisations/individuals, 36 providing substantive input. For a list of all those who commented see Working Group Against Hate Crime (GYEM) (2016, 18 November) summarizing the development of the list.

[17] See Working Group Against Hate Crime (GYEM) (2016, 18 November).

[18] Ibid.

[19] The three column list has been used widely in CSO-police trainings and at internal trainings for members of the police hate crime network.

[20] See Italy national report for recommendations on how to address this.

[21] Phrase used to describe Spain’s progress at Consultation Workshop.

[22] The Observatory is situated in General Secretariat for immigration, emigration, established by legal duty to monitor racism or xenophobic incidents.

[23] Interviewee 2, Spain.

[24] Walters, M.A., Wiedlitzka, S., Owusu-Bempah, A. and Goodall, K. (2017) pp. 67-70.

[25] The strengths and challenges of this approach are explored in section X

[26] Agreement on inter-agency co-operation on addressing racist crimes in Greece (2018, 6 June).

[27] see Schweppe, Haynes and Walters (2018).

[28] Whine (2019) pp. 3-4.

[29] Interviewee 28.

[30] HMICFRS (2014).

[31] HMICFRS (2018) p. 51.

[32] See ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Ireland’ report and Central Statistics Office (2019).

[33] Interviewee 7.

[34] See in particular European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2018b), June and OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) (2014a, 29 September).

[35] Spain launched its first online Hate Crime Victim Survey between March and December 2017, including questions relating to people’s experience of hate crime. The final report will be published later in 2018. However, only around 200 people participated and so cannot be considered a national victimisation survey at this stage; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2018a, January) found that only 9 EU Member States conducted comprehensive victimisation surveys, which include questions relating to victims’ experiences of hate crime.

[36] See also the ‘Standards’ framework, which lists the norms and standards that relate to IGO-national authority cooperation in this area.

[37] Interviewee 11.

[38] This approach is already taken in Spain and the UK

[39] Interviewee 21.

[40] Interviewee 18

[41] Interviewee 5.

[42] Interviewee 15.

[43] Interviewee 13.

[44] This recommendation was accepted at the Italy consultation meeting.

[45] Interviewee 1.

[46] Interviewee 7.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme