The journey of a hate crime case

(cite as: Perry, J. (2019) ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Europe’. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.)

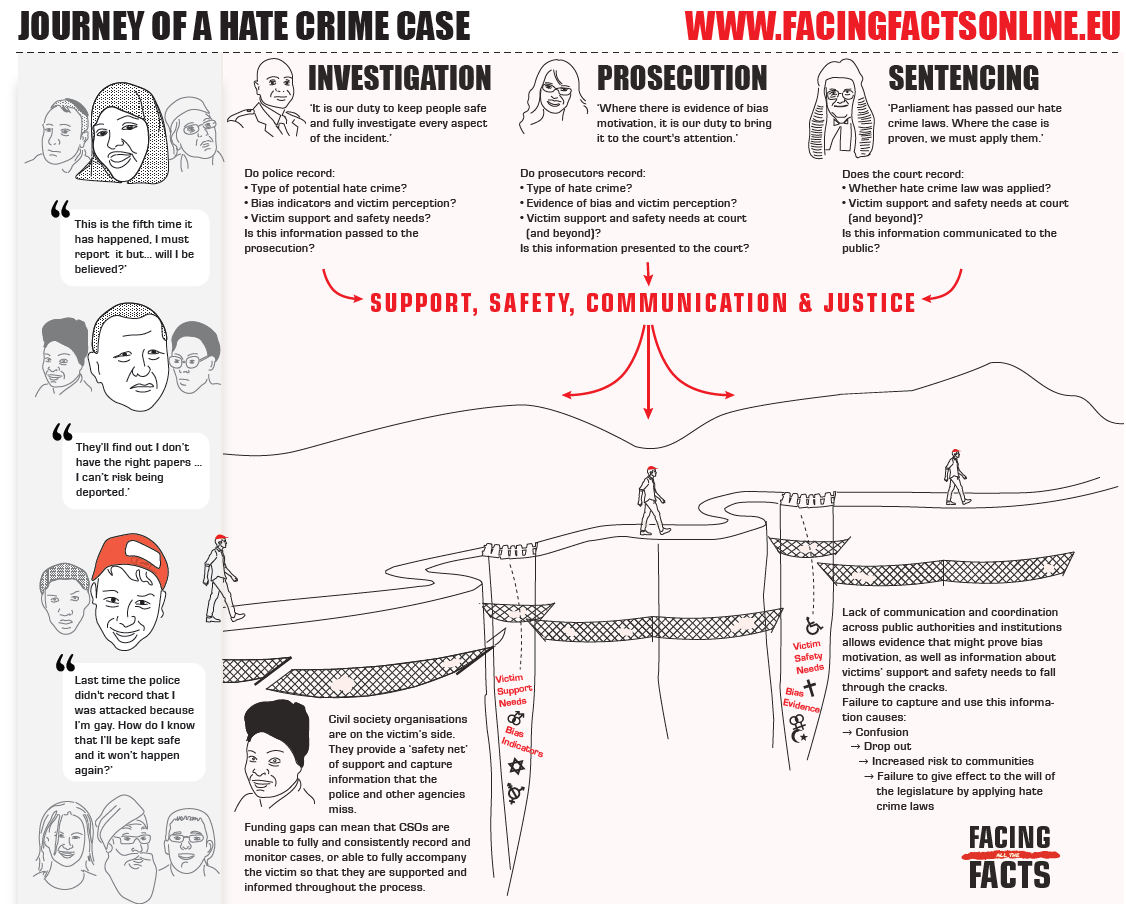

Using a workshop methodology, around 100 people across the six countries taking part in this research contributed to creating a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured if a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[1] Data that ‘can’ and ‘should’ be captured is based on international norms and standards that we critically examined earlier in the report, and that we have compiled in this section.

The Journey graphic below conveys the shared knowledge and experience generated from this exercise. From the legal perspective, it confirms the core problem articulated by Schweppe, Haynes and Walters where, ‘rather than the hate element being communicated forward and impacting the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of the case, it is often “disappeared” or “filtered out” from the process.’[2],[3] It also conveys the complex set of experiences, duties, factors and stakeholders that come into play in efforts to evidence and map the victim experience through key points of reporting, recording and data collection. The police officer, prosecutor, judge and CSO support worker are shown as each being essential to capturing and acting on key information about the victim experience of hate, hostility and bias crime, and their safety and support needs. International norms and standards are the basis for key questions about what information and data is and should be captured.

The reasons why victims do not engage with the police and the criminal justice process are conveyed along with the potential loneliness and confusion of those who do. The professional perspective and attitude of criminal justice professionals that are necessary for a successful journey are presented.[4] NGOs are shown as an essential, if fragile, ‘safety net’, which is a source of information and support to victims across the system, and plays a role in bringing evidence of bias motivation to the attention of the police and the prosecution service.

[lightbox type=”image” src=”https://www.facingfacts.eu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2019/08/Journey-of-a-hate-crime-PNG.png”] [/lightbox]

[/lightbox]

The Journey communicates the normative idea that hate crime recording and data collection starts with a victim reporting an incident, and should be followed by a case progressing through the set stages of investigation, prosecution and sentencing, determined by a national criminal justice process, during which crucial data about bias, safety and security should be captured, used and published by key stakeholders. The graphic also illustrates the reality that victims do not want to report, key information about bias indicators and evidence and victims’ safety and support needs is missed or falls through the cracks created by technical limitations, and institutional boundaries and incompatibilities. It is also clear that CSOs play a central yet under-valued and under-resourced role.

You can find Greek, Hungarian, Italian and Spanish versions of the Journey graphic, along with an explainer video here.

« FINDINGS II BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS FINDINGS IV »

[1] See Methodology Report for further detail

[2] Schweppe, Haynes, and Walters (2018) p. 67.

[3] The extent of this ‘disappearing’ varied across national contexts, and is detailed in national reports.

[4] Based on interviews with individual ‘change agents’ from across these perspectives during the research.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme