Executive summary and recommendations[1]

(cite as: Perry, J. (2019) ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Europe’. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.)

Facing All the Facts builds on the work of the Facing Facts project, established since 2011, to make hate crime visible in Europe. In parallel to the development and delivery of the online training courses for police and civil society organisations,[2] the Facing All the Facts project conducted a participatory action-research methodology across 6 EU Member States that:

- Tested ways to improve understandings of reporting and recording of hate crime;

- Supported shared conversations between the CSOs and public authority actors at the heart of national ‘systems’ of hate crime reporting and recording;

- Created new relationships and collaborations between those actors; and

- Attempted to shift those systems towards a victims-centred and action-oriented approach.

Starting with the first recommendation below, this section highlights the project research’s key findings, and proposes recommendations based on the tools, mechanisms and concepts that were identified, consolidated and developed over the course of three years (2016-2019).

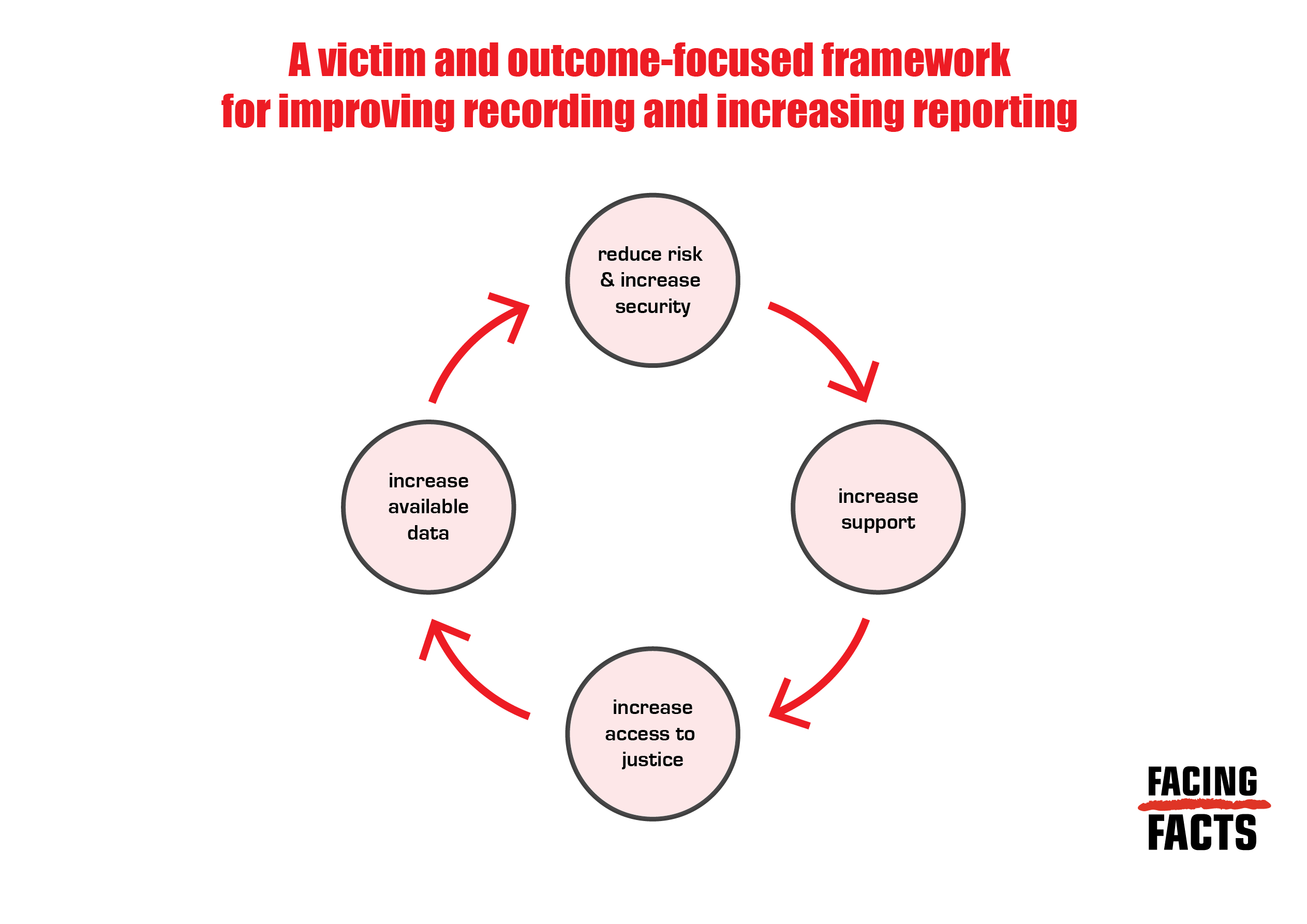

A victim and outcome-focused framework for improving recording and increasing reporting

Simply increasing the numbers of reported and recorded hate crime doesn’t necessarily ensure that victims and communities get what they really need. Urgent questions about what actually motivates people to report and what should drive professionals and policy makers to improve recording were raised throughout this research. As a result, the project endeavoured to articulate an overarching victim and outcome-focused framework for increasing reporting and improving recording:

The overarching purpose of all efforts to increase reporting and improve recording should be to reduce risk, increase access to support and increase access to justice for victims and communities.

This framework is intuitive and simple to grasp. But it is difficult to implement due to the well-documented barriers found across Europe: discriminatory attitudes and actions that discourage victims to report; fear; disconnected technology and policy frameworks that prevent effective recording and information-sharing; and a lack of knowledge, skills and resources to identify and effectively record and act on hate crimes.

In fact, to secure this victim-focused approach, there needs to be a paradigm shift in how institutions see themselves, their partners and their role in preventing and responding to hate crime. Our research findings point to how this shift might best be supported.

Our methodology was designed to enable stakeholders to systematically experiment to identify problems and test possible solutions. Our recommendations aim to be realistic and to complement and develop existing efforts wherever possible.

Recommendations revolve around four areas:

- Making national hate crime reporting, recording and data collection systems visible

- Understanding and using the data that we have

- Building capacity of the various stakeholders involved in national systems

- Continuing to experiment and learn

Making hate crime reporting, recording and data collection visible

No one agency or organisation has sole responsibility for achieving the outcomes identified in the victim and outcome focused reporting and recording framework described above. Instead, every one of the diverse range of stakeholders must see themselves as partners in making hate crime visible, and they must act together for the benefit of victims.

This section summarises how we identified and worked on two initial areas for action to support the development of the connections that must underpin such collective action. First, we collated, critically analysed and integrated all relevant international norms and standards on hate crime recording, reporting and data collection. Second, we used these standards to develop methods to better understand and improve national hate crime reporting and recording systems. Our recommendations for next steps are set out at the end of the section.

Developing the international framework

First we show the development of a complex yet patchy international framework that currently guides public authorities and civil society organisations (CSOs) to increase reporting and improve recording and data collection.[3] Second, we compile these laws, policy recommendations, political commitments and guidelines, to create the first comprehensive Reference of International Norms and Standards on Hate Crime Reporting, Recording and Data Collection. Third, we draw on these ‘standards’ to develop a detailed Self-Assessment Framework on Hate Crime Reporting, Recording and Data Collection. Fourth, we applied the self-assessment to describe, and thus make visible, strengths and weaknesses in national hate crime reporting and recording systems through six national ‘systems maps’: England and Wales, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy and Spain.

Our analysis uncovers a strong framework of norms and standards guiding public authorities to gather data about hate crime investigations, prosecutions and sentences and to conduct victim surveys. Specific standards relate to the importance of victim support, access to justice and increased safety.[4] More recently there has been an increasing focus on the importance of interagency cooperation.[5] Overall, the role of CSO data and action is under-valued, and there is a lack of specificity about what effective cooperation between CSOs and public authorities ought to look like. Finally, there is no normative standard that integrates obligations on improving recording and reporting with the aims of safety, security and justice for victims.

This analysis leads to a recommendation with several parts.

Recommendation 1: International organisations, institutions and CSOs should seek to further develop the international normative framework on hate crime recording, reporting and data collection

This could involve opening a discussion at the international level about the current international framework with a view to further develop standards that:

- Support cooperation across institutional ‘divides’

- Specifically recognise the value of CSO data

- Integrate obligations to, on the one hand, increase reporting and improving recording and data collection and, on the other hand, meet victim and communities’ needs for safety, support and justice.

Adopting a systems methodology and approach

Successful victim and outcome-focused reporting and recording practice requires that relevant stakeholders see themselves as elements of a ‘system’ that needs to work together for the benefit of victims and communities. The project aimed to explore and test ways that would practically support the development of this shared concept at the national level. It did this by engaging stakeholders as active participants in the research process, so that they became both sources for, and targets of, the project’s methods and outputs. Specifically, representatives from law enforcement and criminal justice agencies, ministries and CSOs were brought together—often for the first time—in project workshops and interviews.

In developing the participatory dimensions of the research method we drew on social design research methods, in particular the design-based strategy of ‘making things’ (in our case, hate crime recording and reporting systems) ‘visible and tangible’.[6] Specifically, we facilitated stakeholder workshop participants to co-create physical prototypes of (a victim-centred perspective of):

- The data that is captured and lost as a hate crime case ‘journeys’ (or not) through the criminal justice process; and

- The institutions, stakeholders and relationships that comprise national hate crime reporting and recording ‘systems’

In the process participants were able to share their critical reflections on the ‘here and now’ of national level hate crime reporting and recording, while simultaneously identifying ‘potentialities’ for change and improvement.[7]

Specific steps were taken to engender a safe space for participants to work across institutional boundaries to:

- Negotiate how to present the ‘actual’, for example, the current strengths and weaknesses in reporting and recording processes and institutional relationships. For example, participants were supported to ‘co-describe’ current hate crime recording and reporting systems and to ‘co-diagnose’ their strengths and weaknesses

- Seek agreement on the ‘potential’. For example, participants were encouraged to ‘co-prioritise’ actionable, national recommendations

Feedback and co-produced outputs from the workshops confirmed that national stakeholders appreciated many aspects of this methodology (see Methodology).

There was evidence that the workshops produced:

- Measurable improvements in participants’ understanding of the national ‘picture’ of hate crime

- Significant shifts in how participants perceived their own and others’ role in increasing reporting and improving recording for the benefit of victims and communities

- A willingness of participants to see themselves as elements of a hate crime recording and reporting ‘system’ that needs to be connected and integrated to meet victims’ needs

- Actionable decisions to improve recording and reporting at the national level, such as publishing available data, arranging follow-up meetings between government ministries to improve technical and policy frameworks

- Commitments to explore ways to routinely share data between CSOs and law enforcement

- An appreciation for the ‘structured freedom’ created by the space and participatory, design-informed methodology[8]

The following outputs, initiated by the workshop prototyping process, were refined through interviews and desk research and produced in collaboration with a graphic designer:

- A visual representation of The Journey of a hate crime

- A systems map prototype depicting actual and potential relationships across key stakeholders

- A detailed self-assessment framework, based on international standards for national application

- Six national systems maps (England and Wales, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy and Spain)

- Depicting actual and potential relationships, based on evidence compiled using the self-assessment framework

The following recommendation aims to increase the chance of adopting a systems approach at the national level.

Recommendation 2: Organisations and institutions that are engaged in national capacity-building activities on reporting and recording should draw on tried and tested Facing Facts methods[9]

The methods and tools created by the project can be used very flexibly in capacity building activities led by civil society organisations and/or international or national organisations and agencies. While the highly interactive and collaborative elements of Facing all the Facts might be unusual for some agencies to use, the following principles are strongly recommended for engendering a victim-focused, systems-based approach:

- Include all relevant stakeholders

- Consciously create non-hierarchical, safe and confidential environments

- Use prototyping methods to make national systems visible

- Draw on Facing Facts online learning resources

Understanding and using the data that we have

Many incidents of hate crime that have taken and ruined lives are completely invisible to the general public at the national level. Successfully investigated and prosecuted cases, and initiatives such as laws, national strategies and training programmes can also remain unknown. Evidence of institutional discrimination, a key barrier to reporting and addressing hate crime can be ignored and unaddressed.[10] The techniques and approaches used in this project aimed to contribute to a shared understanding of hate crime by starting to trace and tell the national story of hate crimes and key milestones in recording and reporting.

The project found that flows of information about hate crime data and action to the general public was relatively weak from national authorities, yet relatively strong from CSOs. It also found that both national authorities and CSOs tend to have strong relationships and information flows with IGOs. This suggests a tendency for national authorities to view hate crime recording and data collection as an issue that rests in the international ‘space’, whereas CSOs understand hate crime data as a tool to raise national awareness. The relatively strong relationships between IGOs and national stakeholders is a positive indication that the international framework of norms, standards, capacity building activities and resources, both financial and practical, are influencing and informing national agendas. At the same time, the rich data compiled by IGOs lacks visibility and is under-used by all stakeholders to understand and address hate crime.[11]

The following recommendations focus on steps that can be taken, primarily by IGOs, to develop transparency, coherence and action on hate crime at the national level.

Recommendation 3: IGOs should continue to align hate crime and hate speech working concepts, definitions and capacity building activities across IGOs.

For example, efforts could build on the EC High Level Group’s recent Guidance Note on the Practical Application of the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia, which further clarified the hate crime and hate speech concepts, and supports national efforts to collate and disaggregate hate crime and hate speech data.[12]

Recommendation 4: IGOs should increase the visibility of their annual and ad-hoc reports at the national level

In particular where international reports include national data, IGOs and international agencies should offer insights into how the available national data might be interpreted and used by national policy makers.[13]

Recommendation 5: IGOs should routinely and specifically address Member States that report to international agencies yet fail to prepare transparent information for national stakeholders and taxpayers

If the data and information submitted to IGOs isn’t in the public domain, IGOs should strongly encourage member states to make it easily available in the national language.[14]

Recommendation 6: IGOs should increase transparency about how national efforts on hate crime reporting and recording are assessed

For example:

- OSCE-ODIHR could consider publishing the questionnaire it sends to OSCE Participating States as a basis for preparing its annual hate crime reporting, and publish information about CSO recording methods.[15]

- The Committee for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (CERD) and the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) could consider publishing their methods for taking account of and assessing official and CSO data, when preparing their reports.

- All IGOs and agencies could consider explaining the methods used to assess the veracity of Member States’ assertions about their actions to improve recording and increase reporting, including verifying the existence of guidelines and training programmes.

- All IGOs could stress the need to involve qualified CSOs in the breadth of capacity building activities as an equal partner, including on improving hate crime recording, and not only in initiatives to encourage victims to report or to provide victim support.

- All IGOs could consider developing a method to assess the reliability of CSO data, and integrating CSO data that has been assessed as reliable in their nationally-focused reports and assessments.

Recommendation 7: Eurostat should include a requirement for Member States to collect and submit data on hate crime.[16]

For example, Eurostat and the UN Office for Drugs and Crime could work together to develop criteria for collecting data under the existing category of ‘hate crime’ in the International Classification of Crime for Statistical Purposes (ICCS).[17]

Building capacity

Of course, strengthening the international normative framework and making national systems and data more visible will not automatically lead to positive outcomes for victims and communities. Indeed, the project found that long-established reporting, recording and data collection frameworks, such as those in England and Wales, do not necessarily lead to consistently effective responses for victims and affected communities. In fact, the strongest arguments for integrating reporting and recording strategy with actions to increase access to justice, safety and security came from ‘change agents’ in England and Wales.

Recommendations in this section relate to the practical steps that need to be taken to achieve this paradigm shift, including: technical and policy changes to allow more direct flow of information and cooperation across ‘divides’; actions to strengthen the burgeoning anti-hate crime community in Europe; and, paying particular attention to the strategic questions facing those CSOs that want to conduct high quality monitoring, recording and victim support.

Sharing data and cooperating across the system: implementing and developing technical and policy mechanisms

The Facing all the Facts project found that there are certain mechanisms and approaches that can significantly strengthen connections on hate crime data both between public authorities and CSOs as well as across public authorities, for example between law enforcement and prosecution services.

Interagency policy frameworks and technical capacity building and training programmes are two such mechanisms that facilitate the passing of information on: hate incidents and hate crimes; evidence of bias; and victim support and safety needs. We also found that most countries had an ‘engine of change’ that has sparked and driven the development of these frameworks, and that those countries that have embedded a strategic approach, such as interagency agreements and action plans, are more likely to have stronger ‘systems’.

Bearing in mind the current and relatively strong focus on cooperation across public authorities in IGO capacity-building activities, the following recommendations focus on the interface between public authorities and CSOs. We propose that these ‘cross boundary’ relationships weave the thread of connection between recording and reporting and the right outcomes for victims and communities.

At the technical level, mechanisms that encourage and allow information and data-sharing on victims’ needs and evidence of bias were a particular focus. Our review of the international framework found important support for bringing CSO data into national understandings of hate crime. For example, the Identoba vs Georgia ECHR case found that public authorities should take CSO data into account when assessing the risk faced by LGBT communities.[18] The Victims’ Rights Directive guides public authorities to take account of CSO data when assessing the implementation of the directive at the national level.[19] In practice, there is usually a complete disconnect between CSO and public authority data. The two types of bodies use different definitions, record for different purposes and more often than not, law enforcement do not have the technical means or political incentive to directly take account of CSO data in ways that can inform operational decisions.[20] An exception to this was information-sharing agreements between specialist CSOs and the police in England and Wales, and an official commitment to explore this approach in Spain. Both contexts could be drawn upon for inspiration in this area.

In an effort to move the agenda forward on CSO-public authority cooperation, the recommendation below suggests a focus on the potentially powerful technical mechanism of connection offered by adopting a policy of perception-based recording, which could then allow CSO data to be directly considered and included in the ‘official’ picture of hate crime.[21]

Recommendation 8: Fully implement ECRI GPR No. 11 across all EU member states

The implementation of this recommendation would be supported by the following actions:

- National law enforcement should adopt a policy allowing anonymous reporting[22]

- The international organisations and agencies active in the field should review and revise current standards and guidelines, capacity building and funding frameworks to take a more technical focus, based on clear criteria on the implementation of GPR No 11 at the national level

For example:

- ODIHR could consider including information, as part of its annual hate crime reporting function, on whether a particular country, as a matter of policy:

- Allows anonymous reporting

- Accepts reports from third parties

- Takes the perception-based recording approach

- FRA could build on its 2018 report to further guide states on how to adopt ECRI GPR 11 approach at the national level[23]

- ECRI country reports could consider whether countries have adopted GPR No. 11 in whole or in part, according to clear and measurable criteria

- Take action to better understand and problem-solve national barriers to implementing ECRI GPR 11 in diverse national contexts. Research is needed to explore:

- Current national approaches to implementing ECRI GPR 11 in whole or in part, including alternative innovations and workable models

- Detailed police and CSO perspectives on solutions for partial or full implementation of ECRI GPR 11

- Transferable elements of approaches that have fully implemented third party reporting.[24]

Supporting and connecting those at the centre of change

We found that in addition to strong institutional frameworks for cooperation, inspirational individuals or ‘change agents’ and active ‘critical friendships’ across ‘divides’ are also essential to securing progress towards a victim-focused approach and guarding against regression. Our interviews revealed that each country has dedicated professionals across CSOs and public authorities who are working together to accelerate and safeguard progress in challenging circumstances. There are several steps that can be taken to support those at the centre of these efforts, which are outlined in the next recommendation.

Recommendation 9: Develop and implement professional standards and support networks on hate crime reporting and recording

The key intergovernmental organisations, agencies and CSOs working in this area should explore:

- EU-wide professional standards and accreditation frameworks on hate crime as part of a training strategy. The Facing Facts Online training courses can be considered as a resource which can serve this process

- Creating more spaces for equal engagement and networking that involves ‘change agents’, and learning from formal evaluation of current international structures, including an assessment of how well they support change agents

- Awareness raising and recognition initiatives that could include a European hate crime awards programme and an international hate crime practitioners network

- Further researching success factors in the development and sustaining of ‘critical friendships’ between CSOs and public authorities in a range of political and policy contexts

- Setting up a working group on public authority-CSO cooperation on hate crime recording, reporting and data collection at the European level[25]

All national reports pointed to the challenge of resources, which is connected to what has been labelled the ‘shrinking space’ for civil society. IGOs should recall recommendations by the Commission and by the FRA on actions to better support civil society infrastructure in this context.[26]

There are specific skills that need to be identified and developed if individual victims are to receive the right response at the moment of reporting, which are addressed in the next recommendation.

Recommendation 10: Develop specific learning and standards on providing a victim focused approach to receiving and recording reports of hate crime

Our interviewees echoed existing research findings that hate crimes and incidents are part of a ‘process of victimisation’,[27] of which only part, if any, might be reported. While there has been an important focus on police having the ability to recognise and record the bias indicators that might later prove a hate crime, the person receiving the report, whether police call handler or officer, CSO support worker or other must have the ability and capacity to have the ‘conversation’ that involves:

- Supporting the person to tell their story, which might be unclear, confusing and complex, and/or in a language that isn’t their native language;

- Assessing immediate needs and risks;

- Listening;

- Directly providing or making a referral to support;

- Advising on potential legal outcomes; and

- Identifying and capturing potential bias indicators that could be used as evidence.

Decision makers also need the skill, knowledge and resources to understand what the data is telling them and to commission further work to fill the gaps.[28]

In achieving this recommendation, Facing Facts Online learning can be accessed along with other capacity building tools at the national and international levels.[29]

A focus on CSO recording and monitoring

There is, rightly, significant focus on the role and responsibilities of public authorities in increasing reporting and improving recording and data collection. To date, however, there has been less focus on how to improve CSOs’ ability and capacity in this area and the strategic questions and challenges that they face.[30]

Our findings suggest that a victim and outcome-focused approach requires CSOs to develop a particular organisational orientation that allows them to engage with victims and to secure the trust of affected communities on the one hand, and to effectively and professionally engage with the authorities on the other (see ‘Mechanisms and principles of connection’). It also challenges CSOs to work as a network, across diverse groups to challenge all forms of hate and to meet victims’ intersectional needs. These issues are considered in the following recommendation.

Recommendation 11: European CSO networks and forums should come together to develop guidance on the key strategic questions facing CSOs that want to strengthen victim and outcome- focused reporting and recording activities

Such guidance could consider how to:

- Secure, make visible and implement high quality recording methodologies that protect victim confidentiality, secure the confidence of the communities they represent and provide or ensure support.[31]

- Start and secure practices such as ‘critical friendships’ between public authorities and CSOs

- Navigate hostile political contexts and be open to ‘under the radar cooperation’, while identifying when cooperation isn’t possible due to lack of interest from the authorities

- Work in partnership with other CSOs to adopt a ‘single voice’, which includes:

- Condemning all forms of hate

- Establishing compatible common methodologies

- Seeking common advocacy positions on common issues

- Balancing the risk of competing for the same resources with the need to take a network approach for the benefit of victims and communities

- Evidencing the problem of hate crime even when there is no interest from the authorities. This data can be presented in other fora such as international reports, made visible at the national should the political climate change

- Develop national networks with the support of independent but influential bodies such as equality bodies or national IGO offices.[32]

Continuing to experiment and learn

This research and its outputs have built on deep existing knowledge and inspiring practice. At the same time, there is clearly a lot more to do to achieve a victim and outcome focused approach to increasing reporting and improving recording. Learning has been a key theme across the entire Facing all the Facts project, and we intend to continue learning after this phase ends. The following recommendations focus on key areas for further experimentation and learning including: understanding and addressing risk; compiling and sharing lessons learned from the national implementation of online learning for law enforcement; continuing to develop and improve Facing all the Facts research and collaborative methods; moving beyond a criminal justice focus and securing an increased focus on under-served communities.

Understanding and addressing risk

The focus of existing standards and national efforts tends to be more on assessing and addressing risks to individuals taking part in the criminal justice process, as opposed to the risk of escalation and degenerating social relations posed by hate crimes, hate speech and hate incidents. One of the potential values of collating this type of data is to provide a ‘barometer’ of escalating tensions, which is the focus of the following recommendation.

Recommendation 12: Researchers and IGOs should build the evidential and conceptual basis on which to better address the risks to social relations and community cohesion caused by hate speech, hate incidents, hate crimes and other linked phenomena.

Actions could include to:

- Explore and share how Member States currently use hate crime, hate incident and hate speech data and intelligence to understand and address risks to community cohesion;

- Identify and agree concepts, norms and standards that help connect data on hate incidents, hate speech and hate crime with action to reduce risks to social cohesion.

The online learning ‘frontier’

Facing all the Facts developed online learning for police, pioneering new methods and bringing many challenges for national partners. Developing engaging and relevant content, overcoming barriers in technology, and securing the buy-in of leadership all emerged as key challenges. The following recommendation aims to inform new online learning programmes in other Member States and to improve existing online learning in this area.

Recommendation 13: Facing all the Facts partners should share insights from the implementation of online learning for police in England and Wales, Hungary and Italy.[33]

This could include:

- Technical considerations such as using the Moodle platform for developing and delivering training

- How to disseminate online learning to hundreds/ thousands of learners across federalised or devolved systems

- Countering negative experiences with and perceptions of ‘online learning’

Developing the ‘systems’ approach

The methodology section details the limitations of the Facing all the Facts’ approach. For example, national systems maps do not currently reflect the full complexity of organisational structures organisational data collection systems in each country nor do they reflect the often pioneering work that takes place at the regional and local levels. The following recommendation aims to support further improvements and applications.

Recommendation 14: Facing all the Facts should continue to work with its community of practice to continuously improve its methods and learning through application

This could include:

- Working with national partners to update national systems maps to reflect changes and to identify new areas for action.

- Seeking to further evidence the actions, standards, policies and mechanisms that integrate reporting and recording systems with victim-focused outcomes. Understanding and evidencing relationships across institutional boundaries, especially critical friendships between CSOs and the police is key.

Moving beyond law enforcement and criminal justice

International and national norms and standards overwhelmingly target police and criminal justice responses, yet victims and communities also want and need remedies that can only be found outside the criminal justice process. Further experimentation is needed to connect stakeholders outside the criminal justice system to achieve a truly victim-focused approach to reporting and recording. Focusing on diversity education to influence and change children’s attitudes and developing zero-tolerance policies in the workplace are also important victim-focused strategic goals.

Recommendation 15: Public authorities and anti-hate crime networks should consider methods to involve and include non-criminal justice actors in efforts to ensure victim-focused reporting, recording, data collection and support.

This could include:

- Seeking connections with national partners in health, housing, employment and education to identify existing good practice in:

- Recording hate crimes and incidents

- Supporting victims to access medical care, housing solutions and other local services

- Testing ways, based on Facing all the Facts methods, of bringing these partners into national hate crime reporting and recording ‘systems’ and making their (potential) contribution and responsibilities visible and actionable

Making anti-Roma and disability hate crime visible

A chronic lack of data on anti-Roma and disability hate crime (see the Hate Crime reporting and recording system) highlighted the need for urgent action in this area and is the focus of the last recommendation.

Recommendation 16: Take action to better understand and to improve the reporting and recording of anti-Roma and disability hate crime.

In following this recommendation, stakeholders can draw on:

- The disability hate crime bias indicator online module, which includes learning on common bias indicators, the needs of people with disabilities and their civil rights struggle

- The Roma hate crime module, which includes learning on common bias indicators, the needs of Roma communities and the history of discrimination against them

Understanding and addressing new complexities

While not the subject of specific recommendations, longstanding experts at the heart of national efforts to understand and address hate crime identified several current challenges that need further research and exploration with all affected communities. These include:

- State responses to the migrant and refugee crisis obscuring and exacerbating the nature and impact of hate crimes against long standing minority communities;

- Capturing and meeting victims’ needs arising from intersecting identities and multiple discrimination;

- The limitations of the hate crime framework as a way to understand and address instances of targeted violence between minority communities.

«WHY CONNECT ON HATE CRIME DATA? BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS FINDINGS I »

[1] Recommendations for national stakeholders can be found in national reports.

[2] Facing Facts Online! (2019).

[3] ‘increasing reporting’ refers to standards, frameworks and actions that aim to encourage victims and others to report hate crime to law enforcement or a third party such as a relevant civil society organisation. ‘improving recording’ refers to actions that aim to improve public authority and relevant civil society organisations’ ability and capacity to accurately record hate crime and to pass this information appropriately to other bodies, agencies. ‘improving data collection’ refers to the process of extracting, compiling and interpreting information generated by hate crime recording.

[4] Introduced in 2012, the Victim’s Rights Directive was seminal in recognising hate crime victims’ experience and their right to specific support. The findings of the European Court of Human Rights impose the duty on public authorities to ‘unmask’ bias motivation and are the bedrock of the strategic aim of reporting and recording into access to justice. Finally, assessing and addressing individual risk faced by victims as they engage with the criminal justice process is well recognised by the Victims’ Rights Directive. However, assessing and addressing risk to community cohesion is un-addressed in the current normative framework and is an important area for further exploration. This point is further discussed below.

[5] While there are no policy recommendations or political commitments relating to interagency working, recent joint work between FRA and ODIHR as well as ODIHR’s recently launched INFAHCT programme focus on the technical and policy frameworks that are needed for effective data sharing at the national level. ODIHR’s recently completed project Building a Comprehensive Criminal Justice Response to Hate Crime has supported Greece to implement the necessary strategic policy and technical frameworks in this area.

[6] Manzini (2015); Perry-Kessaris (2017b, 2019 and forthcoming 2020).

[7] Julier and Kimbell (2016) pp. 39 – 40.

[8] Perry-Kessaris (2017b, 2019 and forthcoming 2020).

[9] For example: national workshops run by the newly established FRA Technical and Capacity-Building Unit, joint workshops run by FRA and ODHIR; ODIHR TAHCLE capacity-building activities; all Facing Facts follow up activities and other relevant activities.

[10] See ENAR (2019); see also national report on England and Wales

[11] See European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2018a) and OSCE/ODIHR (2019) for example.

[12] See EU High Level Group on combating racism, xenophobia and other forms of intolerance (2018, November).

[13] See European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2018a) and OSCE/ODIHR Tolerance and Non-Discrimination Department (2019) for example.

[14] This recommendation was accepted at several consultation meetings.

[15] In the same way that OSCE-ODIHR publishes a summary of recording and reporting methods used by public authorities, a summary of the recording methods of the CSOs that report to ODIHR also be included. This would increase and share knowledge on reporting methods and might lead to more aligned recording and reporting processes across public authorities and CSOs.

[16] See Eurostat (2018).

[17] See UNODC (2015, February) p. 100.

[18] ECtHR, Identoba and Others v. Georgia, No. 73235/12 (2015, 12 May).

[19] European Parliament and The Council of the European Union (2012, 25 October).

[20] For example, FRA (2018c, June) found that only 10 member states cooperated in some way with CSOs on hate crime recording. England and Wales are the only country that have information-sharing agreements in place between the police and CSOs.

[21] See European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI) (2007). For a full explanation of how ECRI data can be fully implemented and how the issue is approached in each country, see section [mechanisms of connection].

[22] This is because ‘any other person’ or a third party could include a CSO that is reporting on behalf of a victim who wishes to remain anonymous. Our research found that Greece, Hungary, England and Wales and Spain allow anonymous reporting. Ireland and Italy require the victim to be identified in order for a report to be accepted and recorded by the police.

[23] See European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2018c, June) p. 16-17.

[24] In considering this area, current approaches in England and Wales could be taken into account. For example it is possible to define and limit ‘Third Party Reporting’ sources to ‘professionals’, ‘family members’ and other accredited sources. This could be a useful ‘middle way’ for countries that do not want to accept simply any anonymous report. See Home Office (2019)

[25] The group could consider developing guidelines on how to successfully implement good practice outlined by FRA in a range of contexts, drawing on the principles, mechanisms, methods and frameworks proposed in the Facing all the Facts reports, other research and international standards (see FRA, 2018c).

[26] See this report’s introduction and Council of the European Union (2015), FRA (2018b, January).

[27] Walters, M. A., Brown, R. and Wiedlitzka, S. (2016), see also Chakraborti, N., Garland, J. and Hardy, S. (2014).

[28] These issues are covered in some detail in OSCE/ODIHR (2014, 29 September).

[29] For example, the England and Wales partner in Facing all the Facts developed online learning for police call handlers focusing on these skills

[30] With the important exceptions of ILGA’s and Facing Facts’ guidance and capacity-building in this area. See International Lesbian and Gay Association-Europe (ILGA) (2008) and CEJI (2012).

[31] For example, the Racist Violence Recording Network (RVRN) (see Greece Country Report) shares the same methodology across 32 diverse organisations. This approach needs to be supported by a strong central mechanism that is sufficiently skilled to review data, compile reports, seek cooperation with police, etc. Another approach, followed by the Working Group Against Hate Crime (WGAHC) (see Hungary Country Report) is to bring together a smaller, more focused group that commit to high quality recording and, together, approach police and other organisations for collaboration.

[32] For example, in Greece, the national Human Rights Commission and UNHCR support the work of the Network.

[33] These online learning programmes were developed as part of Facing all the Facts Project. Courses are based on international standards and adapted to national law, policy and practice. Further information about Facing Fact’s Online learning methods and structure can be found at facingfactsonline.eu.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme