Why connect on hate crime data?

If we are to understand hate crime, support victims and reduce and prevent the problem, there are some basic questions that need to be answered:

How many hate crimes are taking place? Who are the people most affected? What is the impact? How good is the response from the police? Are cases getting investigated and prosecuted? Are the courts applying hate crime laws? Are victims getting access to safety, justice and the support they need?

While ‘official’ hate crime data, usually provided by police reports, are the most cited source for answers to these questions, they only tell a small part of this complex story. Understanding what happens to cases as they are investigated, prosecuted and sentenced requires a shared approach with cooperation across government agencies and ministries with responsibilities in this area, however, the necessary mechanisms and partnerships are often not in place. Reports and information captured by civil society organisations (CSOs) can provide crucial parts of the jigsaw, yet connection across public authority- civil society ‘divides’ is even more limited.

There are clear reasons for a lack of connection and cooperation between CSOs and public authorities, many of which mirror those at the heart of why victims don’t report what has happened to them. A lack of trust on both ‘sides’ and a lack of awareness and innovation about what can be achieved through cooperation characterise many public authority-CSO relationships in Europe. Lack of resources and infrastructure to support effective and sustained cooperation also present major barriers. CSOs are often not given meaningful, strategic opportunities to provide input into the design, implementation and monitoring of states’ efforts to measure and respond to hate crime. CSO monitoring data can be dismissed as invalid or unreliable without clear explanation. Police data on specific incidents and trends may not be openly shared.

There are mismatches in perception between police and CSOs about the extent to which hate crime is taken seriously. For example, a 2016 FRA report highlighted that while most law enforcement officers, prosecutors and judges expressed their belief that the police consider investigating bias motives to be very or fairly important, a significantly lower number of staff members of victims’ support services and human rights CSOs held the same view about the police.[1]

These relationships don’t exist in a vacuum. Historical and current social and political contexts affect public attitudes towards and understandings of hate crime as a problem of national concern. While those at the centre of efforts to address hate crime find international frameworks, networks and capacity building of immense support, we show that more needs to be done to nationalise and translate (sometimes literally) the core concepts and characteristics of hate crime in order to drive national, positive change. Cooperation is a ‘practice’ that requires discipline, time and trust. In this research, we tried to get underneath the skin of these relationships and to identify what supports the development of constructive cooperation across NGOs and authorities, and what undermines it.

In several cases in this research, NGOs forced the visibility of hate crime at the national level, leading the way for the police and other public authorities. At the same time, the recording and monitoring methods of many CSOs can lack strength, credibility and transparency leaving public authorities without a partner with whom to cooperate. There is a need to build capacity across CSOs in Europe; the initial aim of the Facing Facts project when it was launched in 2011. As our work evolved, the systemic nature of factors contributing to CSO capacity, led to this research and the development of the Facing Facts Online training platform for both CSOs and law enforcement. (www.facingfactsonline.eu)

Our findings highlight common characteristics of the most successful models for CSO recording, reporting and support. These include highly skilled, networked, services that share a common recording methodology and a commitment to ‘critical friendships’ with the authorities, while allowing for flexibility to meet the needs and secure the trust of their communities. Successful approaches were also characterised by a common commitment to condemn all forms of bias and hatred. Findings highlighted significant gaps in recording and support for people with disabilities and Roma communities. There were also challenges for CSOs working on racist crime where issues of migration are highly politicised.

The Facing all the Facts approach

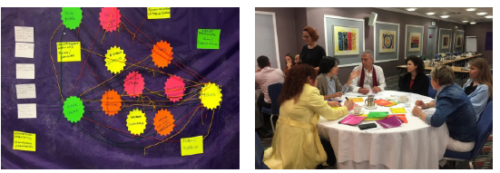

The Facing all the Facts project used interactive workshop methods, in-depth interviews, design techniques and desk research to understand and assess the multi-faceted relationships, frameworks and concepts that comprise a ‘hate crime reporting and recording system’.[2] People were brought together in new ways and challenged to (re)engage with each other and get on the same page about what hate crime is, how it is being made (in)visible and what needs to be done about it for the benefit of victims and communities.

We are grateful for the patience and good humour of our workshop participants as they built images of national ‘systems’ using string and glue!

Another core theme across our efforts was to find ways to support stakeholders to understand themselves as equal and essential parts of the reporting and recording process and system. We did this by:

- Ensuring, as far as possible, representation from across the public authority and CSO perspectives at workshops and as interviewees

- Developing participatory methods that brought diverse stakeholders together during workshop activities

- Developing graphic representations of all stakeholders on the same ‘page’, depicting the journey of a hate crime case and representations of national hate crime reporting and recording ‘systems’

- Creating an integrated, victim and outcome focused model for increasing reporting and improving recording.

This participatory and design-informed approach facilitated the emergence of what we now understand as the “journey and systems concept” which reflects two key principles. First, victims’ and community experiences of hate crime are not punctual events, but lived over time, potentially through the criminal justice system if they report, and through the impact it has on their day-to-day lives, whether or not they report. Second, there is a range of institutions and organisations that could or should be engaged directly or indirectly through the victim’s journey (police, prosecutors, judiciary, victim support organisations, international organisations, etc.). When these “stakeholders” recognise and play their part within a system of connected actors, victims are more likely to have satisfactory results from their journeys.

Each country presents a different picture, and none is fully comprehensive or balanced. It is hoped that national stakeholders can build on the findings and recommendations to further understand and effectively address the painful and stubborn problem of hate crime in each country.

The international context

Over the course of the research, public authorities, policy makers and CSOs consistently identified the international framework of norms and standards, IGOs capacity-building guidelines and programmes as well as professional networks as central sources of strategic influence and support in efforts to improve hate crime reporting, recording and data collection.

In line with the project’s participatory and policy-focused research methodology, it was decided to ground outputs in an explicit, international normative framework that would have practical value.

As such, the report presents this framework from several angles:

- As a dynamic timeline illustrating key milestones in its development, illustrating its piecemeal and complex character as well as the recent intense and active focus of key international organisations and agencies

- As a reference document, simply listing the main norms and standards in the area

- As the basis of a diagnostic assessment, to be used by national authorities, CSO and IGOs to co-describe, co-diagnose and co-prioritise actions for improvement. The diagnostic assessment is based on two measures: the strength of policy and technical frameworks that support reporting, recording and information- sharing, and the presence and effectiveness of action

- As a basis for further development, especially in relation to deepening cooperation between public authorities and civil society organisations

This report documents the outcome of these efforts and concludes that a strategic “victim and outcome-focused model” must be integrated into current norms, standards, policies and practice that are relevant to reporting, recording and data collection at the international and national levels. While improving national and international databases of reported and recorded hate crimes, prosecutions and sentences is important, it cannot be the ultimate goal. Rather, our collective efforts to increase reporting and improve recording and data collection should aim higher to secure support, protection and justice for victims and communities.

Shrinking spaces

In its 2015-2019 Action Plan on Human rights and Democracy, the EU acknowledged the ‘shrinking of civil society space worldwide’[3] and pledged to deepen its cooperation with and support of civil society, and stated that it was ‘profoundly concerned at attempts in some countries to restrict the independence of civil society’.[4] It also committed to supporting ‘structured exchanges’ between CSOs and public authorities and ‘address threats to NGOs’ space’.[5] The ‘critical friendships’ between law enforcement and CSOs that we identified as essential to authentic and effective cooperation exist within these ‘shrinking spaces’ and there is a need to support and protect them.

International norms and standards and national policies and laws provide a framework for cooperation. However, much more work is needed to spark and sustain effective action. The methods of connection and cooperation explored, experimented with and articulated by the Facing all the Facts project can lead to a more connected position on what needs to be monitored, prioritised and how.

Supporting the ‘anti-hate crime community’

We do not underestimate the challenges of hostile political environments and the chronic lack of resources across Europe. However, we are inspired by the people we have talked to whose lives have been forever changed by hate and yet who work to raise awareness and to stop it happening to others. We are also inspired by the dogged determination of our ‘change agents’ who are personally and professionally driven to find solutions and to move the agenda forward. Through their voices, presented in this report, we see the development of what one interviewee called, an ‘anti-hate crime community’ of professionals across CSOs, law enforcement and the criminal justice system who are determined to work together to make the problem of hate crime and ways forward, visible and actionable.[6] We hope that the ideas, tools and recommendations offered by this research help these efforts.

Robin Sclafani and Joanna Perry

BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY & RECOMMENDATIONS »

[1] European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2016).

[2] The following countries were involved in this research: Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom (England and Wales).

[3] European Commission (2012) p. 5.

[4] European Commission (2012) p. 12.

[5] European Commission (2012) p.19.

[6] Interviewee 30.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme