A victim and outcome-focused framework for improving reporting and increasing reporting

(cite as: Perry, J. (2019) ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Europe’. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.)

A strategic approach that connects national systems to meaningful action should drive efforts to increase reporting and improve reporting. Without it, the ‘data’ that is generated could be meaningless. As one interviewee asked, ‘what is the number that tells you there is a problem?’.[1] Another asked,

‘….what is the target, what are we trying to achieve? An increase [in reporting] by 10% achieves what [we] want? But an increase of 10% isn’t a long term strategy. That isn’t getting to people…How do we deal with the volume if we are successful, and give the right response? What is [our] foundation for dealing with this and how [can we] make sure that people have a good first conversation?’.[2]

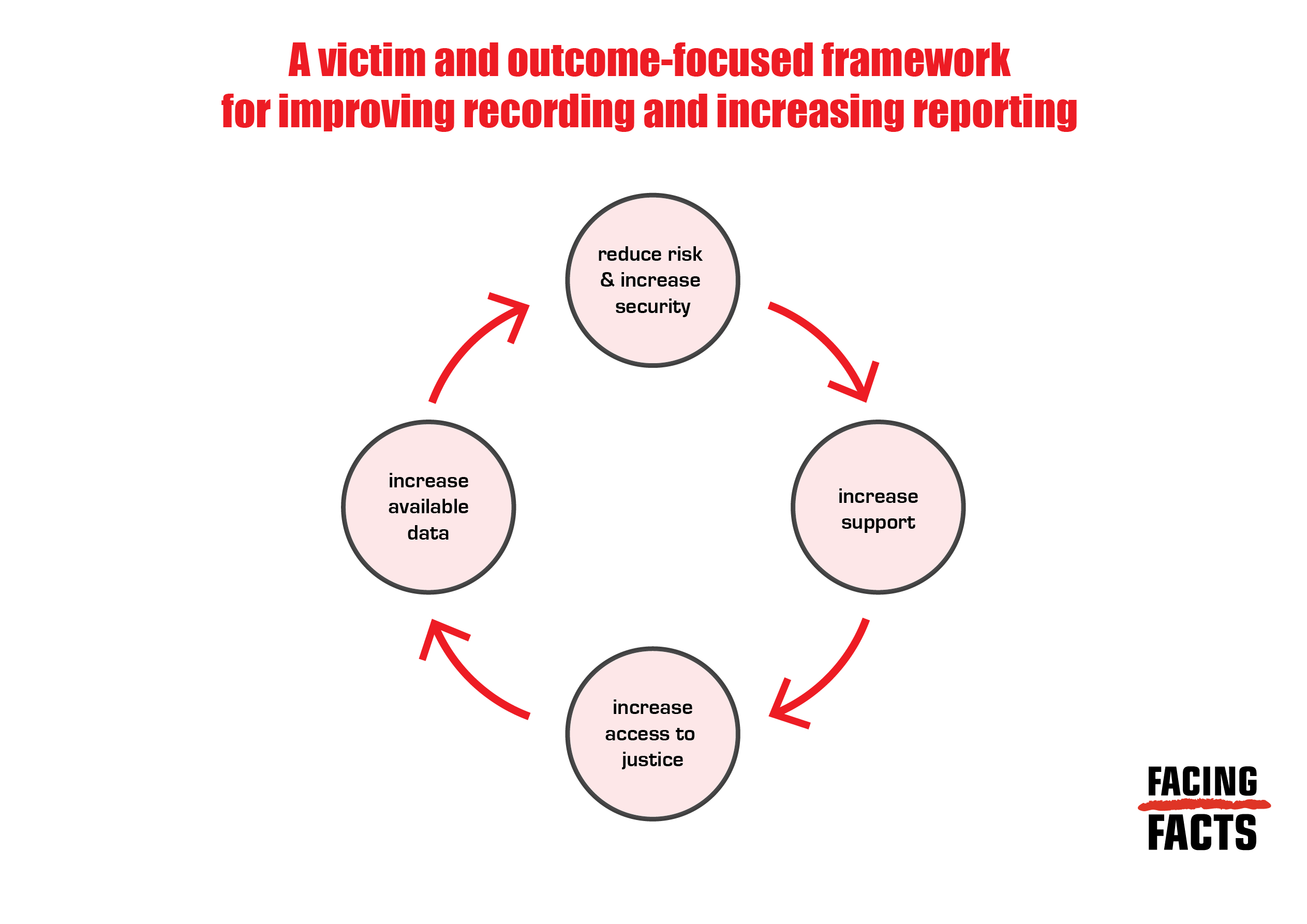

The research has identified four victim and action-focused outcomes that national reporting and recording systems should aim to secure.

These are to:

- Increase available data

- Increase access to support

- Increase access to justice

- Reduce risk and increase protection

The graphic below shows these elements as equal, inter-dependent and connected.

It can be tempting to see hate crimes and incidents as single recordable occurrences that victims simply need the confidence to report and CSOs and public authorities simply need the facility and skill to identify and record. While many victims may know that they or someone they know has been targeted because of hostility towards or bias against their identity they are likely not to know that it is called a ‘hate crime’ or that they are entitled to a particular response under the Victims’ Rights Directive and relevant national laws. Further, hate crimes and incidents against victims and communities are likely to be part of a ‘process of victimisation’.[3] Incidents can take place over time, in different forms and locations, affect different people in different ways, include criminal and noncriminal acts and be a part of broader patterns of discrimination that shape affected communities’ ongoing sense of safety and belonging. These elements can be present in various combinations at the moment of ‘reporting’. The receiver of the report, whether a police officer or call handler, CSO representative or other individual, needs the skill and space to have the ‘conversation’ that allows the ‘story’ to emerge and recordable and actionable information to be captured.

The rest of this section examines each strategic outcome in more detail, reviews the standards that underpin them, explores examples from the research and starts to identify what needs to be in place to successfully implement this model.

Outcome one: increase available data

Just over half of all identified standards (23 out of 43) relate to achieving aim one.[4] These standards particularly focus on the importance of gathering accurate information about the number of hate crime investigations, prosecutions and sentences and the importance of obtaining and publishing ‘comparable data’. Reasons given for these actions tend to be aimed at policy makers, to get ‘an overview of the situation’, and to ‘contribute to’ the effective implementation and evaluation of national and EU law. Some standards do not connect the need to obtain data with any particular outcome. Several standards focus on the importance of conducting victimisation surveys that include questions on hate crimes, to uncover the ‘dark figure’ of hate crime at the national level. Some standards focus on the interface between IGOs and national governments, with the former serving as a gathering point for information and the latter having obligations to supply it. Three standards, relate to the role of CSOs in recording hate crime and using it to connect with public authorities and with targeted communities.

Aiming to increase reporting and improve recording in order to better understand the nature, prevalence and impact of hate crime and the extent to which relevant national and European laws are being implemented are important aims, especially for decision makers. However, without grounding this outcome in a victim focus, the connection between data collection and effective action is potentially weak. We now turn to a consideration of those aims that focus on improving victim safety and their access to support and justice.

Outcome two: Reporting and recording into support

Reporting and recording into support should be a key strategic aim of any national system, yet there was little basis in international standards for making this connection until the passing of the Victims Directive, specifying the rights that victims are entitled to, including information, support and protection.[5] Clearly these rights cannot be realised without a system that encourages victims to report, identifies hate crime victims and their needs and uses the information to ensure that they are met. As explained, the Directive also requires that available information indicating whether victims have accessed their rights, including information from CSOs, is sent to the Commission. There is one other standard, derived from guidance produced by CSOs relating to the role of CSOs to refer victims to support.[6]

The importance of connecting reporting and recording systems with support, assessment and referral was explored in depth in the England and Wales report, which considered the impact on reporting rates of the relatively longstanding government policy of establishing ‘third party reporting centres’. These centres can be led by different services including specialist organisations and local authorities and take several forms including physical locations frequented by community members such as libraries, social clubs, mosques, and day centres, or online, telephone and through apps.

There is evidence that physical reporting centres are not being effectively used. Research in Scotland found that 89.3% of respondents working at third party reporting centres reported that the centre had either been inactive or not very active the previous year. A 2014 review cited in a recent report by the national police inspectorate, found that physically located reporting centres ‘failed to deliver tangible results’. The inspectorate concluded based on its own findings, ‘It appears that little has changed since this review….’[7]

Research has suggested that low levels of third party reporting shows both a lack of awareness about the existence of these alternative routes, and a need to explicitly connect reporting with specialist support.[8] As one interviewee asked,

‘Is success getting as many reports to the police as possible or as many prosecutions as possible or is success getting as much support to victims out there as possible, depending on what they might need?’[9]

Research undertaken in Northumbria, England, found that as the support and outreach element of a regional third party reporting network was reduced and then stopped, the number of reports it recorded drastically reduced from 800 in 2012 to 54 in 2015.[10] Evidence from Ireland suggests that an organisation’s inability, due to a lack of resources, to offer support had a negative impact on the number of reports it received.[11] An interviewee from an organisation working with LGBT+ communities in Italy felt that reporting couldn’t be encouraged without being connected to direct support, explaining,

‘We stopped recording [hate crimes]. But why, not because it is not important, but the problem was that there were so many that we could no longer afford to go through the recording process and to offer help’[12]

Conversely, specialist community organisations such as the Community Security Trust and Tell MAMA in England and Wales that are resourced to provide support to victims, and work closely with the police, record relatively high numbers of hate incidents.[13],[14] Other research found that local, specialist, grassroots organisations are best known to victims and important sources of support, even if structured reporting services are not available.[15]

While there are a number of factors that influence levels of hate crime recording and reporting, this review suggests that a national policy that aims to simply increase the number of reported hate crimes whether directly to the police or through third party reporting should be integrated with the equally important need to improve routes into support and thus improved outcomes for victims. The importance of ensuring connection across the strategic aims of the proposed framework starts to emerge.

Outcome three: Reporting and recording into justice

Encouraging victims to report, capturing evidence, including their perception, of whether hate or bias was involved in the offence, and supporting them to remain engaged in the criminal justice process are essential if hate crime laws are to be applied and justice served. Reporting and recording into justice is well supported by international standards, especially judgments from the European Court of Human Rights which oblige national authorities to obtain and record or ‘unmask’ evidence of the hate element of hate crimes and ensure it is passed on through the criminal justice process.[16]

The research also indicated that non-criminal justice outcomes can be an essential aspect of justice for victims of hate crime. One interviewee pointed out, ‘a criminal justice response is one way of addressing the issue of hate crime but there are all sorts of other issues – housing, health, etc.’[17] Another interviewee added, ‘many people don’t want a criminal justice outcome. If we really are trying to get everyone to report all incidents, the police can’t help in many of them’.[18] Other research shows that victims are often open to alternatives to punishment including restorative justice.[19]

Victims’ lived experience and the process of victimisation that they find themselves in will lead to a range of needs including health and housing, yet the current international framework focuses almost exclusively on obligations and rights relating to criminal proceedings, and on criminal justice agencies and their ministries. National policy on reporting and recording outside of the policing and criminal justice sphere is also weak. The recommendations section considers how to broaden the current framework to better reflect victims’ lived experience.

Outcome four: Reporting and recording into prevention and risk assessment

Hate crimes pose risks to individual victims in terms of repeated and escalating offending, and risk a dangerous breakdown in community relations. While these risks are often referred to in statements by IGOs, only one standard was identified that takes a practical and victim focused approach to risk assessment.[20] The Victims’ Rights Directive directs Member States to ‘ensure a timely and individual assessment to identify specific protection needs…paying particular attention’ to victims of hate crime.[21] A recent FRA publication refers to the importance of using bias indicators to identify risk, ‘crucially, bias indicators can be compelling evidence that a victim or their community faces a serious and possibly imminent risk of escalating harm or even death. As such, it is a core law enforcement responsibility to record and actively use bias indicators to assess levels of risk and to take appropriate safeguarding action to protect their right to life.’[22]

The online learning developed as part of Facing all the Facts for police in England and Wales focuses on the importance of risk assessment and risk factors – which are also common bias indicators – such as being labelled a ‘paedophile’ or a ‘terrorist’. The ECHR judgement Identoba and Others vs Georgia concluded that, ‘given the history of public hostility towards the LGBT community in Georgia, the Court considers that the domestic authorities knew or ought to have known of the risks associated with any public event concerning that vulnerable community, and were consequently under an obligation to provide heightened State protection.’[23]

This process of reporting and recording into protection and safety is the fourth strategic aim for national reporting and recording systems.

Identifying the improved assessment of risk as a strategic aim of hate crime reporting and recording policy prioritises the crucial need to improve the intelligence picture relating to specific incidents and trends and reduce risks faced by victims, communities and societal cohesion. However, the research found that in England and Wales there is evidence that there is not a consistent approach to risk assessment for hate crime cases. Operational Guidance for British police sets out recording obligations and directs police to conduct risks assessments. However, the national police inspectorate found that, ‘only 56 out of 180 [cases] had an enhanced risk assessment completed. This is deeply unsatisfactory.’[24]

A commonly understood role of the police should be to prevent crime and protect victims, indeed risk factors are usually a core focus in the policing of domestic violence. Perhaps surprisingly, how risk is understood, assessed and addressed in national policing approaches to hate is an underexplored area worthy of further research. [25]

As pointed out in part one of the report, there is a general gap in standards relating to the importance of interagency cooperation and connection between national authorities and across CSO and public authority divides. Similarly, no standards explicitly point to the connections and interdependencies across the four strategic outcomes. This gap is further discussed in the recommendations section.

What skills need to be in place to give life to this framework?

Notwithstanding the well-rehearsed barriers faced by victims to report hate crimes,[26] to achieve outcomes two, three and four, the person receiving the report, whether police call handler or officer, CSO support worker or other must have the ability and capacity to have the ‘conversation’ that involves:

- Supporting the person to tell their story, which might be unclear, confusing and complex, or in a language that isn’t their native language

- Assessing immediate needs, including risks

- Listening

- Providing or referral to support

- Advising on potential legal outcomes

- Identifying and capturing potential bias indicators that could be used as evidence

To achieve outcome one, decision makers need the skill, knowledge and resources to understand what the data is telling them and commission further work to fill the gaps. For example, an increase in police-recorded crime is likely to indicate an increase in reporting and/or improved reporting as opposed to an increase in the incidence of hate crime. Low numbers of particular types of hate crime such as disability hate crime is likely to indicate low reporting and a need to increase frontline police awareness of how to identify and record it and community awareness that these are crimes that should be reported.[27]

Connecting process, system and outcomes

There are clear connections across the project’s other main findings encapsulated in the journey and system concepts. The journey visualises the linear process of reporting and recording as a case progresses through the criminal justice process. The systems maps evaluate the necessary relationships that support this process. This framework articulates the core outcomes that should underpin all efforts to increase reporting and improve recording, pointing to the particular skills, knowledge and partnerships that need to be in place. However, because the framework emerged in the final stages of analysis, it is yet to be tested directly with stakeholders. Further, observations on the connections among support, protection and access to justice are relatively focused on England and Wales because examining the strengths and weaknesses of current third party reporting policy emerged as an important line of exploration in that context. Future work could share the model with public authorities and CSOs that have relevant obligations and knowledge, and test its usefulness and applicability to national planning in this area. In addition, more focus on what is currently in place in the five other countries at the national level would be useful.[28]

Finally, there are implications for the current international normative framework when considering integrating the outcomes of reporting and recording into support, into reducing risk and into access to justice. While relevant and powerful elements of this framework can be found in the Victims’ Rights Directive, its obligations and rights only apply to criminal offences and focus on the criminal justice process and individual assessments of risk. More work is needed to explore how data on hate crimes and non-crime hate incidents gathered in other contexts such as housing and education can be used for intelligence purposes and to help identify risks to community cohesion. Further, current capacity-building activities should consider the necessary technical and policy frameworks and skills and knowledge to deliver these outcomes.

Table matching outcomes with international norms and standards on hate crime reporting and recording

| Aim | Standards and comment |

|---|---|

| Increase available data on investigation, prosecution, sentencing and prevalence for decision makers | 2, 4, 6, 7, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 27, 28, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43 |

| The right first response and access to support and information is secured | 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19, 29, 38 |

| Risk is identified and reduced | 5 (indicates less consideration of this issue at the international level) |

| Positive criminal justice, and other, outcomes for victims and communities are achieved | 1, 3, 15 (no mention of non-criminal justice outcomes) |

« FINDINGS V BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS FINDINGS VII »

[1] Interviewee 20.

[2] Interviewee 27.

[3] Walters, Brown and Wiedlitzka (2016).

[4] see standards 2, 4, 6,7, 17, 20, 21, 22, 23, 27, 28, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 39, 40, 42, 43.

[5] See standards 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 19, 29.

[7] HMICFRS (2018) p. 63.

[8] Chakraborti and Hardy (2016).

[9] Interviewee 35.

[10] Clayton, Donovan and Macdonald (2019).

[11] See Ireland country report. For example, an organisation monitoring anti-trans hate crimes, which did not have the resources to offer support recorded a decrease from 20 to 15 reports between 2015-2016. While there might be a number of reasons for the low number of reports, the lack of resources for support is likely to be a factor.

[12] Interviewee 5, Italy.

[13] The Community Security Trust works with Jewish Communities, Tell MAMA works with Muslim communities.

[14] See Community Security Trust (2018); Tell MAMA (2017).

[15] Chakraborti, Garland and Hardy (2014).

[17] Interviewee 29.

[18] Interviewee 27.

[19] Chakraborti, Garland and Hardy (2014); Walters (2014).

[21] Victims’ Rights Directive, Article 22 (European Parliament and The Council of the European Union, 2012).

[22] European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) (2018b, June) p. 20.

[23] see ECtHR, Identoba and Others v. Georgia, No. 73235/12 (2015, 12 May) para. 72.

[24] HMICFRS (2018) p. 63.

[25] See for example, Trickett and Hamilton (2016).

[26] See Journey graphic

[27] These issues are covered in some detail in OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE/ODIHR) (2014, 29 September).

[28] Greece, Hungary, Italy, Ireland and Spain.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme