Facing Facts online: Where research and learning design meet.

How we use our research findings to inform our online learning design

From the beginning of the Facing Facts journey, our core aim has been to develop tools and methods that make hate crime’s prevalence and impact more visible to those who have a responsibility to do something about it. We quickly realised that to achieve this aim, we ourselves had to better understand what really supports effective hate crime reporting and recording systems in diverse contexts across many communities.

From 2016 to 2019, the research component of the Facing All the Facts project, worked to do just that. Our partnership of NGOs and public authorities in six countries:

- tested new and collaborative ways to improve understandings of reporting and recording of hate crime;

- supported shared conversations between the CSO and public authority actors at the heart of national ‘systems’ of hate crime reporting and recording; and,

- created new relationships and collaborations between those actors.

We used the evidence generated from this research process to produce four key outputs – a timeline and three graphics. Our dissemination strategy was not just to present our findings, but to create learning tools to use in our online programmes.

Before we give you a tour of these tools, here is a little more background about our learning communitiy.

Facing Facts Online learners represent NGOs, researchers and public authorities including the police, prosecution services, ministries and equality bodies. They work in diverse contexts around the world and share a common interest in strengthening their skills in identifying, recording and monitoring hate crime, and a motivation to improve their understanding of victims’ rights and needs.

Facing Facts online courses on hate crime monitoring and recording are a mix of bespoke and open access courses. They tend to involve 30-40 participants and take place over a period of 4-6 weeks. Check out Melissa Sonnino’s blog for an overview of two recent open courses for more information. We have also designed programmes for police organisations in Hungary, Ireland, Italy and England and Wales. You can read Lucia Gori’s blog to learn more about developing online learning for the police in Italy.

Timeline of developments

The first thing to do in our research was to set out where we are on the key norms and standards on reporting and recording. Telling the story as a timeline shows that although there have been standards in this area as far back as 1965, with the passing of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination (ICERD), it’s only quite recently that intergovernmental bodies and agencies have really focused on giving clear guidance and offering capacity building to their member states.

We have used the timeline to tell the story of how the complex, uneven network of norms that we currently have came about and to show that there is still a long way to go before the value of NGO and CSO hate crime data and the importance of cooperating across NGOs and public authorities is fully acknowledged in the international anti-hate crime community.

We often use this tool at the beginning of our online programmes to set the context for our learners.

We hope in future courses to support our learners to develop their own timelines to describe and make sense of their own contexts, similar to our Facing all the Facts country reports which include timelines that trace the development of national hate crime reporting and recording systems.

Journey of a hate crime case

As our research progressed, we saw that it was important to show what hate crime data should be collected by whom and how it gets lost as case progress through the criminal justice process. As we explain in our report, we used a workshop methodology, involving around 100 people across the 6 countries to create a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured along this journey from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, alongside the role of the key stakeholders involved.

In recent courses, we mapped international standards against these key stages of the journey using an interactive image, to support participants to understand the practical implications of the many international norms and standards in the area of hate crime reporting and recording.

We have also seen users refer to ‘falling through the cracks’ and ‘journeys’ in the discussion forums as they share and express the challenges and perils of their own context. Recently a participant told us that he printed out an A3 copy of the Journey and pinned it to his wall to remind him of the criminal justice process, how data should be gathered, and where the ‘gaps’ and ‘cracks’ are most acute in his national context.

Mapping national hate crime reporting and recording systems

As set out in the introduction, one of our aims was to support shared conversations between the CSO and public authority actors at the heart of national ‘systems’ of hate crime reporting and recording. Again, we used a workshop methodology to produced six national ‘systems maps’ that aim to: present those actors at the national level that play a key role in hate crime recording and data collection; and, to describe the strength of relationships across the system based on specific criteria. The criteria for asessing the strength of these relationships are: whether there is the right policy and technical framework to support improved reporting, recording and data sharing across relevant insitutions and organisations; and, whether these policy and technical frameworks are implemented and used effectively. We have a simple colour-coded rating system for ‘green’, ‘amber’ and ‘red’ relationships among institutions and organisations that have a responsibility to make hate crime visible and to respond effectively.

Images from workshops in Greece, which show how the systems maps started!

The systems maps process is quite intense! They were produced over two workshops, supported by intensive desk research and collaboration between the lead researcher and national partners. Here we can see the complexity of Spain’s systems map below.

Spain’s system map as of September 2019. You can click on the + signs, or ‘hotspots’ to see the evidence for each of the relationship assessments.

Although the systems concept pervades our approach to online learning, we are still researching ways to support participants to create their own systems map. For our research we used Adobe to create the basic maps as an image, and H5P to set the interactive hotspots with the evidence that we used to evaluate and rate each relationship. Along with the workshop methodology and intense research, the process is too cumbersome and inaccessible for learners who want to build their own maps over a much shorter four week period. We are now exploring more accessible technology to allow control and more efficient experimentation– watch this space!

Victim and outcome framework

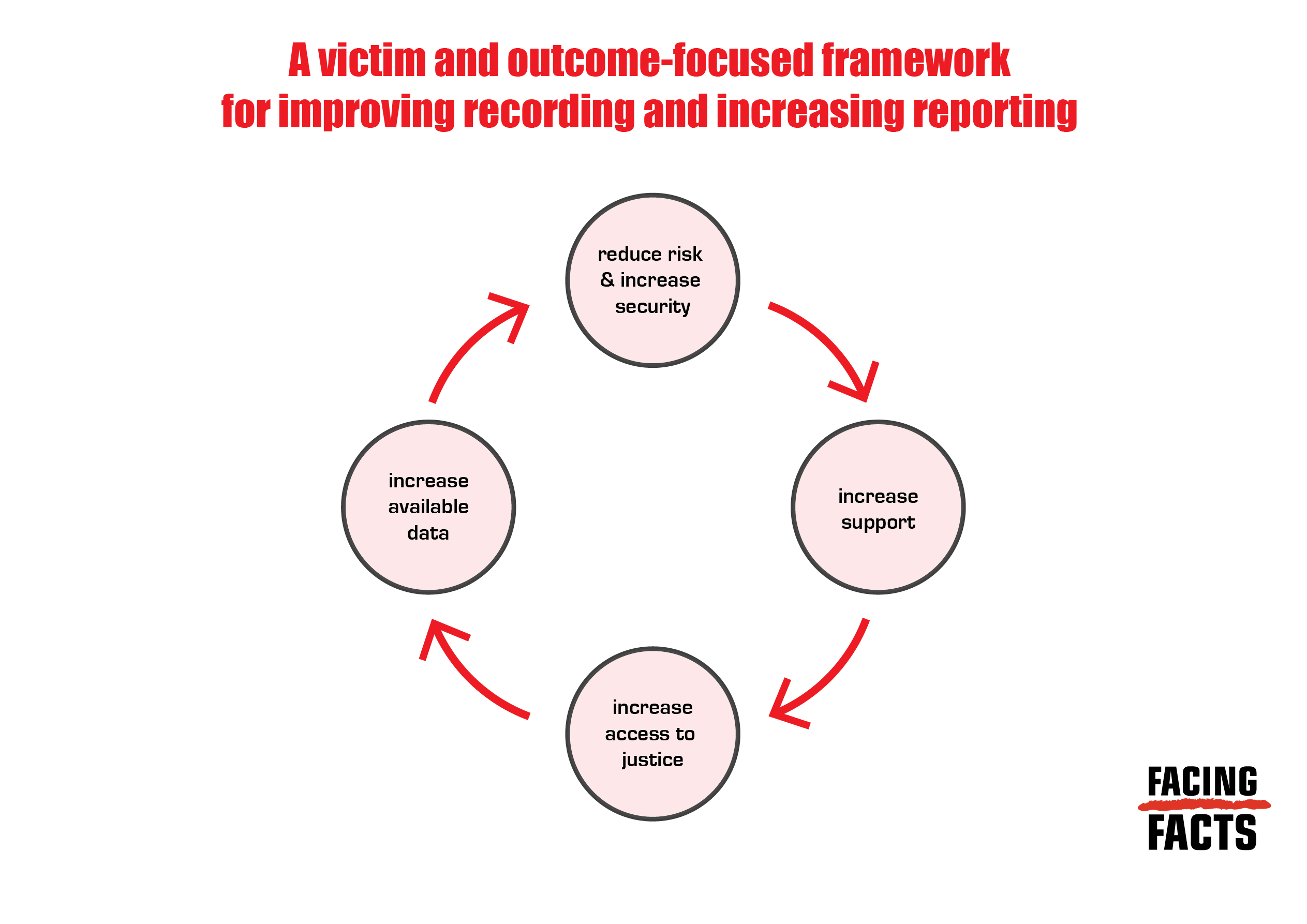

Towards the end of the Facing all the Facts project, it became clear that efforts to improve recording and increase reporting cannot just be aimed at generating data for the sake of having data. Yes, it is important to send statistics and data to ODIHR for their annual hate crime reporting and to FRA for their reports, but the process and efforts need to be focused on meaningful outcomes for victims. Our victim and outcome framework aims to communicate this central finding. We find that in our online learning programmes, the graphic and accompanying video are very useful to frame and guide discussions about the purpose of efforts to improve recording and increase reporting.

So there you have it – four key research outputs that we use in our online learning programmes!

How have you used your research findings to inform your online learning design? Let us know in the comments section below!

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Leave a Reply