Haider / El-Gamal (2023), Connecting on hate crime victim support in Austria. Brussels: CEJI. Edited by: Joanna Perry. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan.

Download the full report in PDF here.

Introduction and background[1]

If we are to understand hate crime[2], support victims and reduce and prevent the problem, there are some basic questions that need to be answered:

How many hate crimes are taking place? Who are the people most affected? What is the impact? How good is the response from the police? Are cases getting investigated and prosecuted? Are the courts applying hate crime laws? Are victims getting access to safety, justice and the support they need? How do the various stakeholders within the victim support system work together and interact?

While ‘official’ hate crime data, usually provided by police reports, are the most cited source for answers to these questions, they can only tell a small part of this complex story. Understanding what happens to cases as they are investigated, prosecuted and sentenced requires a shared approach and cooperation across government agencies and ministries with responsibilities in this area, however, the necessary mechanisms and partnerships are often not in place. Reports and information captured by civil society organisations (CSOs) can also provide crucial parts of the jigsaw, yet connection across public authority – civil society ‘divides’ is even more limited. In terms of victim support, victims often lack the necessary information about the support system potentially available to them. Referrals of victims to other organisations within the support system, in cases where additional support is needed, could lift the victims burden of finding the necessary information and contacting various organisations on their own.

Since 2016, Facing Facts has been developing interactive workshop methods, questionnaires, graphic design and desk research to understand and assess frameworks and actions that support hate crime recording, data collection and exchange and victim referrals across a ‘system’ of public authorities and CSOs as well as among CSOs. The approach involves a participatory research methodology and working directly with those at the centre of national efforts to improve hate crime recording, data collection and victim support to explore the hypothesis that stronger relationships across the hate crime recording, data collection and victim support system lead to better data and information about hate crime and support of victims.

Building on the Facing Facts’ final European report’s findings, also in the Austrian context it became clear that a range of factors are key to progress in this area, including the:

- strength and comprehensiveness of the international normative framework that influences national approaches to recording, data collection and victim support;

- technical capacity to actually record information and connect with other parts of the system to share and pass it on;

- existence of an underlying and inclusive policy framework at the national level;

- work of individual ‘change agents’ and the degree to which they are politically supported;

- skills and available resources of those civil society organisations that conduct recording, monitoring, support and advocacy;

- interaction and coordination among the support system’s stakeholders;

- existence of a legal basis for formalized victim referral mechanisms to ensure victims benefit from the available support system.

In 2022-2023 Facing Facts Network member ZARA worked with the Facing Facts team to adapt this methodology to the Austrian context. This national report aims to describe the context and current picture of hate crime recording data collection and victim support in Austria and to present practical, achievable recommendations for improvement. It is hoped that national stakeholders can build on its findings to progress in this critically important piece of broader efforts to understand and effectively address the painful and stubborn problem of hate crime in Austria.

It is recommended that this report is read in conjunction with the European Report, which takes a broader focus and brings together themes from across six other national contexts, tells the stories of good practice and includes practical recommendations for improvements at the European level.

Research questions

The research was guided by the following research questions:[3]

- How can the Facing all the Facts methodology support in developing a functioning referral system, including a data recording and data collection system in Austria, by

- co-describing the current situation (Who are the stakeholders supporting hate crime victims in Austria? Who is collaborating how? What do the relationships regarding referrals look like?);

- co-diagnosing gaps and issues (Where are the gaps? Which stakeholders need to be included more? What is missing on a technical level? What needs to be done?), and;

- co-prioritising actions for improvement (What are the most important things that need to be done now and in the future? How can we further foster collaboration on that?).

- To what extent can an online tool be helpful for elaborating a system map in a participatory and interactive way?

The project combined traditional research methods, such as questionnaires and desk research, with an innovative combination of methods drawn from participatory research and design research.[4] The research team consisted of Facing Facts, ZARA, which is an Austrian specialist civil society organisation (CSO) in the field of anti-racism work, and an independent researcher.

How did we carry out this research?

The following activities were conducted by the research team:

- An early decision was taken to focus on CSOs’ role in a hate crime support system. Starting from an already existing network[5] in Austria coordinated by ZARA, network members as well as additionally identified CSOs with potential contacts with people affected by hate crime were invited to a workshop. Public authorities invited at this point were limited to the Austrian Ministry of Interior and the Ombud for Equal treatment, as they had already been members of the network and had been closely collaborating with CSOs[6] on that specific topic. The first workshop’s main objective was participants self-identification as a part of the Austrian hate crime victim support system and of their role therein. Participants exchanged and discussed their practices of hate crime data collection, service provision for hate crime victims as well as referrals and working relationships within the system.[7] The workshop took place in Vienna on 11 November 2022.

- Conducted an evaluation at the end of the workshops via Mentimeter to collect feedback on participants’ experiences.

- Sent out a survey to CSOs, the Ombud for Equal treatment, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Justice to gain their insights into our research questions. From the 67 CSOs with potential contacts to people affected by hate crime 16 civil society organisations survey responses were collected. The survey asked CSOs and the Ombud for Equal Treatment if and how they are in contact with hate crime victims; in which region they operate; whether and how they collect statistical data on hate crime and if yes, whether those statistics are published; whether they offer legal advice and/or counselling services; whether they refer clients to other organisations and whether there exist any formal agreements or lived practice in terms of regular data exchange and/or victim referrals with other organisations/institutions. The surveys sent to the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Justice focused more on questions regarding victim referrals to CSOs as well as the working relationship and problem-solving practices between the ministries and their subordinated public authorities. In addition, all participants were asked to assess their working relationships with each other.

- Gathered information via desk research to complete an overview of current hate crime reporting, recording, data collection and referral processes and actions at the national level, based on a pre-prepared template[8]. In particular, the research looked at referral processes and actions from both support and data exchange points of view.

Existing methodologies and frameworks developed by Facing Facts were adapted to the Austrian context as the basis for the workshops and this report. The self-assessment grid developed by Facing Facts is a document setting out evidence that can be used to understand and describe current strengths and weaknesses across the relationships that form national hate crime monitoring and response systems. It uses scores (0-6) and colour coding (green for a score of 5-6, amber for a score of 3-4 and red for a score of 0-2) as a quick reference system to compare existing national policies and actions with international norms and standards on hate crime data collection and victim support. It aims to build on and complement existing approaches to synthesise international norms and standards on hate crime [9]

For example, the ‘Journey of a Hate Crime Case’ visualisation was already available in German and previously used by ZARA within network meetings and other project activities[10] like trainings with professionals. The material helped to bring all participants of the workshop to a similar level of knowledge on international norms and standards regarding the support of hate crimes victims. During the first workshop, a first version of a system map outlining the relevant stakeholders and their relationships among each other was developed by participants using a ‘sticky wall’ and was then transferred into an online tool.[A2]

Participants’ experiences of the first workshop

The Mentimeter evaluation allowed to gather some valuable feedback on participants experience of the first workshop. Initially, participants were asked to describe in three words how they felt after the workshop. The words mostly used were “networked”, “motivated” and “tired”. Other words also used by several participants included “enriched”, “informed”, “more connected” and “instructive”. In addition, some participants felt “linked”, “happy”, “strengthened”, “optimistic”, “blessed”, “curious”, “keen to debate”, “inspired” and “excited”. Participants agreed or strongly agreed that the workshop helped them to

- understand the importance of making hate crime more visible through improvements in recording and increased reporting (4.5 points; scale 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree);

- understand what a national referral system for hate crime victims is (4.4 points);

- identify their role/perspective within the national referral system for hate crime victims (3.9 points);

- identify their relationships within the national referral system for hate crime victims (4.0 points);

- assess the strengths and weaknesses of their relationships within the system (3.9 points);

- understand the strengths and weaknesses of other relationships within the system (4.0 points);

- identify specific actions they can take (3.4 points).

Next, participants were asked if they were able to collect any innovative experiences in the course of the workshop. Responses addressed both methodological and practical points. In terms of the methodology, participants highlighted the interactive mapping process, the immediate visualization techniques during the workshop as well as the live evaluation of the workshop. Content-wise, participants learned the importance of networking and getting to know other stakeholders involved. One participant highlighted: “The benefit of having an established way of referrals between ngos, preferably specific persons responsible for the referral in each ngo.” Another participant pointed out that border cases between hate crime and discrimination should be treated by systematic interinstitutional exchange.

Furthermore, participants were asked to name the kind of support they would need to feel (more) as a part of the system. Responses varied and could be categorized into the need for

- financial resources and funding, especially for networking activities;

- structured regular exchange and networking among stakeholders, especially regarding the status quo of the system map;

- clear competencies/points of contact in each organisation;

- “[a]greements between the ngos for referrals”;

- “more hate crime-trained contact points at the police”;

- “[a]uthorities should call us experts (what we are) and not just members of a Community”;

- more information on any legal gaps and the specific situations of victim groups as the basis for the implementation of measures, actions and cooperation;

- legislation providing (more) protection for victims.

Second research phase

Consequently, the information gathered from the first workshop, its live evaluation as well as the findings from the survey and desk research fed into a first draft of the national report including the self-assessment document annexed. In addition, a second version of the system map was created via an online tool based on the draft self-assessment document and its colour coding of the various relationships. This second version of the system map was therefore based on the preliminary findings of the research, while the first version, which was created during the workshop, was based on participants self-identification and assessment.[A3]

Following this first phase of the research, it was decided that more connection and momentum would be generated, and a more accurate and meaningful final report would be produced, by including all stakeholders in the process and directly consulting on the preliminary findings. For that purpose, a second interactive online follow up-workshop was held on 28 February 2023. It was decided to not restrict participation to those organisations, which had taken part in the first workshop, but to again invite all 67 CSOs, the Ombud for Equal treatment, the Ministry of Interior as well as the Ministry of Justice. This was because the second workshop’s objective focused on further developing the Austrian hate crime victim support system including exchange among participating stakeholders. While this approach proved beneficial for the workshop’s objective, it provided challenges integrating those participants who were new to the process. The research team responded to these challenges by providing a brief recap and outline of previous steps at the beginning of the workshop. Following this initiation, the second version of the system map was presented and participants were reintroduced to the online tool used. Consequently, participants were allocated into small groups, each facilitated by a member of the research team, to encourage participants to interactively use the online system map and discuss the preliminary research findings it reflected.

Participants experiences of the second workshop

Also, the second workshop was concluded by participants’ live evaluation via Mentimeter. On the one hand, participants agreed or strongly agreed that the workshop helped them to

- better understand their role within the national referral system for hate crime victims (3.4 points; scale 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree);

- better understand the strengths and weaknesses of the relationships important to them (3.2 points);

- better understand the options available to address these strengths and weaknesses (2.9 points);

- feel more motivated to take further actions (3.3 points);

- have a clear conception of the next steps our group should take (2.8 points).

On the other hand, participants were more indecisive on whether the workshop helped them to have a clear conception of the next steps their organisation should take (2.5 points). This reflects the workshop’s primary objective and focus on promoting meetings and exchange among stakeholders as well as the system as a whole, as a first step. In consequence, the research team identified the need for clearer guidance for organisations to navigate, actively participate and ‘use’ the system as an important task for following phases.

In addition, participants were asked to indicate what they liked and disliked about the online tool Lucid, which had been used by the research team to create the system map, was presented and used during the workshop and was intended to serve as an interactive platform for the Austrian national system in the future. Several participants indicated that they needed more time to have a closer look at both the online tool and the preliminary findings it reflected. The point was made that their use in the workshop without any prior options for participants to prepare had not been ideal. In addition, participants missed more detailed background information on which basis the system map and its relationships had been explored. The research team reflected on this critique by internally discussing options to find a better compromise between information and user-friendliness for future workshops. One participant also disliked the obligatory registration process by providing an e-mail address. On a positive note, participants liked the interactivity and found the tool participatory and useful to provide an accessible and up to date overview of the system.

In terms of any remaining open questions, one participant highlighted that they were unsure how to now create a sustainable national network.

Third research phase

Following the second workshop, some additional and previously missing information was gathered from the authorities and together with the evaluation of and reflections on the second workshop fed into the revised final draft report.

Most importantly, the research team took strategic decisions on the role and objective of the project report on the one hand and the online system map on the other hand. It was decided that the report should be finalised at this stage. As its primary objective, it has the purpose to provide information about the status quo of the Austrian national referral and data collection system for hate crime victims to both the system’s participants and the general public. Secondly, it serves to document the process of establishing and fostering the system up to this point. The report and its appendixed self-assessment document intend to inform readers about international standards on hate crime victim support and compare them with the current national situation in the following three specific areas: stakeholder cooperation, victim referrals to ensure the best possible support, and data collection.

It was reflected that an even more thorough participatory process on intensifying cooperation within the system can only start once all participants have the same level of information on both the international standards and the national situation. One goal of this report was the identification of specialist organisations working on hate crime as a basis for a data transfer and potential victim referral system from grassroots towards specialist organisations. Bearing this aim in mind, the report can and does not list all organisations that we consider as part of the hate crime victim support system. It cannot provide detailed descriptions of every organisation’s treatment of hate crime cases. In addition, experiences from other countries show that, regularly, only specialist organisations have closer liaisons with the relevant authorities on hate crime related topics.[11] That is another reason why streamlining information towards specialist organisations was considered as a promising strategy for future developments.

In terms of the online system map, a snapshot of its current version has been included into this report. Additionally, it was decided to also use the online system map as a living document, potentially to be accessed and updated in the process of the system’s further development and assisted by members themselves.

The following sections provide an overview of the hate crime concept’s evolution in Austria and selected findings of this project regarding the status quo of data collection, service provision to and referrals of hate crime victims within the Austrian system.

The ‘story’ of hate crime in Austria: a timeline

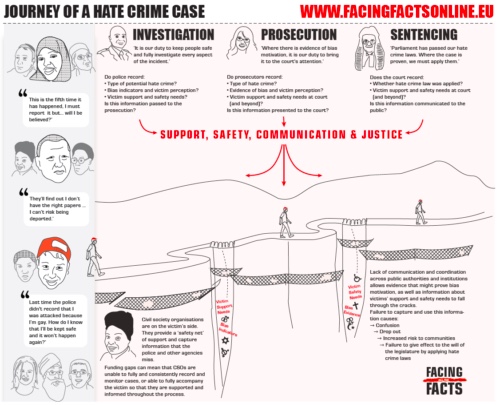

The journey of a hate crime case[19]

In previous research, in which around 100 people across 6 countries took part, a workshop methodology was used, to create a victim-focused, multi-agency picture about what information is and should be captured as a hate crime case journeys through the criminal justice system from reporting to investigation, prosecution and sentencing, and the key stakeholders involved.[20]

The Journey graphic conveys the shared knowledge and experience generated from this exercise. From the legal perspective, it confirms the core problem articulated by Schweppe, Haynes and Walters where, ‘rather than the hate element being communicated forward and impacting the investigation, prosecution and sentencing of the case, it is often “disappeared” or “filtered out” from the process.’[21] It also conveys the complex set of experiences, duties, factors and stakeholders that come into play in efforts to evidence and map the victim experience through key points of reporting, recording and data collection. The police officer, prosecutor, judge and CSO support worker are shown as each being essential to capturing and acting on key information about the victim experience of hate, hostility and bias crime, and their safety and support needs. International norms and standards[22] are the basis for key questions about what information and data is and should be captured.

The reasons why victims do not engage with the police and the criminal justice process are conveyed along with the potential loneliness and confusion of those who do. The professional perspective and attitude of criminal justice professionals that are necessary for a successful journey are presented.[23] NGOs are shown as an essential, if fragile, ‘safety net’, which is a source of information and support to victims across the system and plays a role in bringing evidence of bias motivation to the attention of the police and the prosecution service.

The Journey communicates the normative idea that hate crime recording and data collection starts with a victim reporting an incident and should be followed by a case progressing through the set stages of investigation, prosecution and sentencing, determined by a national criminal justice process, during which crucial data about bias, safety and security should be captured, used and published by key stakeholders. The graphic also illustrates the reality that victims do not want to report, key information about bias indicators and evidence and victims’ safety and support needs is missed or falls through the cracks created by technical limitations, and institutional boundaries and incompatibilities. It is also clear that CSOs play a central yet under-valued and under-resourced role.

Mapping Austria’s hate crime recording, data collection and victim support ‘system’[24]

The ‘linear’ criminal justice process presented in the Journey graphic is shaped by a broader system of connections and relationships that needs to be taken into account. Extensive work and continuous consultation produced a victim-focused framework and methodology, based on an explicit list of international norms and standards, that seeks to support an inclusive and victim-focused assessment of the national situation, based on a concept of relationships. It integrates a consideration of evidence of CSO-public authority and CSO-CSO cooperation on hate crime recording, data collection and victim support as well as evidence relating to the quality of CSO efforts to directly record and monitor hate crimes against the communities they support and represent.[25] In this way it aims to go beyond, yet complement existing approaches such as OSCE-ODIHR’s Key Observations framework and its INFAHCT Programme.[26] The system map also serves as a tool to support all stakeholders in a workshop or other interactive setting to co-describe current hate crime recording, data collection and victim support systems; co-diagnose its strengths and weaknesses; and co-prioritise actions for improvement.[27]

The interactive ‘Systems map’ below is best viewed in full screen mode (click on the icon in the top right hand corner of the map). Click on the ‘+’ icons for an evidence-based explanation of the colour-coded relationship, based on international norms and standards.

Or download Self-assessment grid on hate crime recording and data collection, framed by international

norms and standards – AUSTRIA (pdf).

Commentary on system map

Austria only recently initiated a strategic approach to identify and record hate crimes on the official level. A positive effort was the flagging of hate crime cases in the police case file system and its interconnection with the electronic case management system of the criminal justice system. Both law enforcement and the criminal justice system are now able to comprehensively record hate crimes. While law enforcement implemented a relatively detailed system to record various bias motivations and indicators, the criminal justice system currently only records an overall ‚hate motive‘, without disaggregating by bias motive. The prosecution legally assesses every case and decides whether to press charges, close the proceedings or offer a diversion. The prosecution may request the criminal police to gather further evidence. Where the prosecution identifies a potential hate crime the relevant facts and evidence need to be gathered and, if charges are pressed, presented, irrespective of whether the case had been previously flagged as a hate crime by the criminal police.

Together with the introduction of the systematic hate crime recording system, law enforcement rolled out multilevel and extensive trainings. The e-learning program on hate crime created for and used by law enforcement has been made accessible to all judges and prosecutors, extended by an additional module created by the Ministry of Justice. Joint trainings of law enforcement, prosecutors and judges so far have been held on online hate speech but not on hate crime. It appears that the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Justice have a good working relationship in the field of hate crime. Inter-ministerial meetings to review progress and address shortcomings appear to take place both on an annual/semi-annual basis as well as case- and project-related.

A major negative aspect of the Austrian system is the lack of a comprehensive national strategy or action plan to combat hate crimes systematically. The government has so far heavily relied on single measures here and there, often in reaction to pressure from or funded by international or European institutions. Hate crime has no priority on the national agenda. One consequence of this strategic gap is that the entire Austrian support system of hate crime victims lacks a coordinating force. While some civil society organisations are currently trying to fill this gap, despite their best efforts, they simply lack resources and power. Tasks like the creation of a single point of information for victims, the collection and joint analysis of hate crime data from various sources, raising awareness among and informing the public and the implementation of a comprehensive system of regular referrals and knowledge exchange between all public and civil society stakeholders typically need to be coordinated by a adequately funded designated agency or ministerial department. The human rights department of the Ministry of Interior sets a good example and shows commitment both inside their own ministry and in liaison with other stakeholders. However, their efforts and resources need to cover a variety of human rights related issues and it can therefore not serve as a substitute for some sort of focused point of competence.

Within the field of civil society organizations, the Ombud for Equal treatment, and other anti-discrimination bodies, there are about a handful of organisations that have been active in the support of hate crime victims and raising awareness on the topic for many years. On the other hand, many organisations that focus their work on different or broader fields, regularly get in contact with hate crime victims. Among this latter group, some record (explicit) hate crime statistics while others use different categories or non-statistical case documentations. Client referrals and knowledge exchange across civil society organisations take place but on a rather sporadic, non-systematic basis. In those cases where civil society organisations had consultations with each other, respondents reported positive experiences.

There appears to be good coverage across all communities in terms of counselling services. However, it has been reported that there is some under-representation of statistics of cases of disability hate crimes. Organisations offering counselling services to or representing people with disabilities have only recently begun to work with the concept of hate crime and often have other priorities (e.g., issues such as independent living and equal access to work, housing, health and education; in terms of incident reporting, organisations indicated a higher relevance of cases of violence or of hate incidents that are not crimes). On the other hand, organisations focusing on counselling services for hate crime victims have little to no contact with this community. In terms of anti-LGBT+ hate crimes and in comparison to the other communities, fewer statistics and data are published by those organisations that focus their work on the support of LGBT+ communities. Unfortunately, LGBT+ communities still face much discrimination in Austrian society and lack strong anti-discrimination laws. Therefore, collecting and publishing hate crime statistics might not be a priority for organisations working with these and other similarly marginalised communities.

Respondents suggested to develop an agreement among CSOs regarding questions like which data should be collected, where to bring them together and/or to create an online reporting system, which can be fed by all relevant stakeholders.[28] In addition, it was recommended to share clear information on who is competent in which field, to be able to refer clients purposefully. Several respondents recommended creating the legal basis to share necessary data with other organisations, to secure referrals without having to get victim’s approval. However, any kind of automatic referral system needs to respect victims’ rights and data protection laws.[29]

National context

The next sections give context to the ‘journey of a hate crime case’ and the ‘system map’ and present themes gathered through the first workshop and a survey among civil society organisations, equality and anti-discrimination bodies monitoring hate crimes or otherwise getting in contact with hate crime victims, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Justice.

Initiation of official systematic hate crime recording in 2021

Until November 2020 no systematic identification and recording of hate crime was taking place. Only right-wing extremist crime under the subcategories racism/xenophobia, antisemitism and islamophobia had been reported as ‘hate crime’ to ODIHR.[30] Funded by an EU project, law enforcement implemented comprehensive trainings and systematic identification and recording of hate crimes in November 2020. Relevant information in hate crime cases is since then collected through a tick-box system within the electronic police case file database.[31]

The Ministry of Justice introduced systematic hate crime recording in March 2021. Hate crimes are flagged as bias motivated crime (vorurteilsmotivierte Straftaten – “VM”) in the justice system’s digital registers (Verfahrensautomation Justiz und EliAs). The bias motivations identified and flagged by law enforcement are automatically transferred into and recorded in the justice system’s digital registers together with the police crime report.

The hate crime statistics for 2021 submitted to ODIHR show an increase in recorded cases since the implementation of systematic hate crime recording. 5,464 hate crime cases were recorded by the police, 4,304 cases were prosecuted and 184 cases were sentenced.[32]

Referring clients to law enforcement ‘[…] in the hope that the competent officer is sensitised enough’

The relationship between law enforcement and civil society organisations, equality and anti-discrimination bodies is characterized by unsystematic cooperation on a case-by-case basis. Several organisations describe that in their experience, both the quality of investigations and how the victim is treated, highly depend on the skills and commitment of the case handler.

‘[…] There is a differing and superficially correct cooperation, in criminal proceedings attorneys also point out misconduct, disinterest, etc. … partly, in our cooperation it is also visible that some officers are very correct, understanding and dedicated in the field of hate crime.’[33]

‘[…] Police is not always the same as police, but there are a lot of different officers and units. Some are very supportive, record the case, inform victims about their rights, organise translators, secure evidence or assist in doing so. Others do not take victims seriously, do not record the case, etc. Improvement: comprehensive trainings (and not only for those interested), clear operational processes and contact persons.’[34]

‘[…] We are not in contact with the police. People concerned often tell us that they do not want to turn to the police or report their case because they fear that they would not be believed. A really sensitised representative or contact person, who takes their time for victims of hate crime, ideally upon arranging an appointment, [so that there is time] eventually to also file a report.’[35]

It appears that in regions where the same professionals on both sides meet regularly, e.g. there is a regular working relationship between specific case workers and/or police reports are regularly filed with the same police station, there is less fluctuation in the quality of services. One respondent from outside Vienna explained, referring to the project’s ‘green’, ‘amber’ and ‘red’ assessment:

‘Green in most cases as we accompany [clients] to interviews and this is also known with the police.’[36]

A major concern, especially for civil society organisations working on racist hate crime, is the lack of an independent and effective complaints system regarding police misconduct and law enforcement’s reluctance to record and investigate hate crimes committed by police officers.

‘The complaint system of the police is too inaccessible. For two years now, we were unsuccessful to be named a contact person […]. However, now it is planned to have an exchange with “Gemeinsam Sicher”[37], maybe this will lead to a better cooperation. Unfortunately, we regularly have reports on racial profiling. We would like to discuss them with the police in […].’[38]

On the other hand, several organisations praise their cooperation with the human rights department of the Ministry of Interior:

‚[…] Problems can be discussed.‘[39]

‘[…] Through the “Hate Crime Kontern Network” we are in contact and exchange regarding hate crime. However, not regarding particular cases.’[40]

“Good cooperation – green, in particular with the human rights department of the MoI, very good exchange and knowledge transfer as well as commitment!!!!”[41]

Room for improvement of inter-organisational cooperation

In terms of the relationship between the Ministry of Justice/criminal justice system and civil society organisations, equality and anti-discrimination bodies, it is striking that the two sides’ assessment of the situation stand in stark contrast. While the Ministry of Justice perceives itself to have good relationships with CSOs, CSOs’ opinions appear to be divided between two groups. Cooperation seems to exist only with CSOs working in the broader field of crime victim support and/or being appointed organisations to provide psychosocial and legal support in criminal proceedings (Prozessbegleitung). Most CSOs focusing their work on hate crimes or not mainly working with victims of crime commented that no relationship or cooperation existed. This indicates that there are currently no specific networking efforts in place regarding the topic of hate crime.

‘There is no cooperation except with a judge who offers meetings for exchange, interpretation of cases, etc. (of course not regarding specific pending cases).‘[42]

‘[…] There is no cooperation. Also here, a direct sensitised contact person would be desirable.‘[43]

‘Adequate cooperation – […], because there is room for improvement – too little knowledge regarding hate crimes.‘[44]

‘[…] however, so far rarely any specific cooperation on that matter.‘[45]

‘Bad cooperation – […], because they want to play their cards close to their chest and believe they don’t need any support.‘[46]

One organization also criticized a lack of providing victims their participation rights in criminal proceedings:

‘In need of improvement: consideration of victims’ interests, consideration of the victim’s right to make a statement concerning diversions, informing the organisation providing support services to victims during criminal proceedings (Prozessbegleitung) and the victim about discontinuing the proceedings and diversions, the reasons provided when proceedings are discontinued are often very insufficiently argued[.] There is sometimes the impression that the organisations providing support services to victims during criminal proceedings (Prozessbegleitung) are perceived as [only] creating work for the prosecution regarding their requests.‘[47]

Shortcomings in the referral system of hate crime victims

Referrals are currently done on a case-by-case basis by most stakeholders. Referrals including any non-anonymised data exchange between stakeholders require the victim’s approval. Only in cases where a person is at risk of violence or stalking and a restraining order is issued by law enforcement, an automatic referral mechanism is in place between law enforcement and designated victim support organisations. In such cases, law enforcement informs special intervention organisations, who then contact the person at risk and offer their support.[48]

It appears that the shortcomings of the optional referral system are twofold. At the level of law enforcement, an obligatory referral mechanism seems preferable to ensure formalized processes. Also, the Ministry of Interior recommended the implementation of an automatic referral mechanism like the one in existence in the field of domestic violence protection. At the CSO level, a lack of clarity can be perceived as to which organisations exist and which services are provided.

‘[…] We would wish for a legal basis for referrals of victims of situative violence and that the police would use the option to refer victims upon their approval when reporting. It depends on the individual police officer with whom we are in contact, from green to amber to red, everything is possible, but in general it is red to amber.’[49]

‘With some organisations we are well interconnected and have an exchange also regarding specific questions. We refer clients to the respective institutions and they do the same. Contact persons on the topic of hate crime in the respective organisations would be helpful to intensify the exchange.’[50]

‘In counselling centres there should be clear guidelines where to refer clients to.’[51]

(Incomplete) list of CSOs currently providing specialist counselling and/or recording in hate crime cases[52]

| CSO | Hate crime counselling | Hate crime recording | Region | Bias motivations/ communities |

| Anti-discrimination Office Salzburg[53] | Legal advice | Yes | Salzburg | All |

| Anti-discrimination Office Styria[54] | Legal advice and support at interviews with the police and taking legal action | Yes | Styria | All |

| Dokustelle Islamfeindlichkeit & antimuslimischer Rassismus[55] | Legal advice and psychosocial counselling | Yes | Austria | Islamophobia and anti-muslim racism |

| Initiative für ein Diskriminierungsfreies Bildungswesen (IDB)[56] | No | Yes | Austria | All; focus on incidents in the education system |

| IKG Wien/ Antisemitismus Meldestelle[57] | Unknown | Yes | Austria | Antisemitism |

| 24h-Frauennotruf[58] | Psychosocial counselling and legal advice; support in criminal proceedings | No | Vienna | Violence against women, misogyny, lesbophobia |

| WASt[59] | Psychosocial counselling and legal advice | Not explicitly | Vienna, Austria | LGBTIQ |

| Weisser Ring/Opfernotruf[60] | Psychosocial counselling and legal advice; support in criminal proceedings | Yes | Austria | All |

| ZARA[61] | Legal advice and support at interviews with the police and taking legal action | Yes | Vienna, Austria | Racism (including anti-Muslim, anti-Roma, etc.) |

Conclusion and Recommendations[62]

Although Austria’s progress has only recently begun, a strong commitment of individual actors of several initiatives and institutions can be felt. Especially the efforts of and cooperation within the Network countering hate crime – coordinated by ZARA – with its members of CSOs and public authorities (the Human Rights Department of the MoI) can be seen as a “hybrid engine of change”[63]. The collaboration and proactive work on hate crime reporting and recording as well as engagement with IGOs in the last years are the basis of the “engine”. Nevertheless, a missing framework and strategic system-wide approach makes the endeavours of the “hybrid engine of change” vulnerable to changes and harbours the risk to remaining individual efforts.

The following recommendations aim to consolidate and support further progress, with a focus on better aligning client referral, data collection and data exchange efforts across public authorities, institutions and towards those CSOs that are already specialist and effective in recording and monitoring hate crimes and supporting victims.

- Provide funding for the establishment and operation of a structured hate crime victims referral system as well as exchange and networking platforms like the Network countering hate crime as its basis.

- Continue to identify specialist CSOs that have effective systems in place to record hate crimes and offer victim support.

- Create a list of the specialist CSOs working on hate crime and provide it to other (grassroots) organisations potentially in contact with hate crime victims. Include detailed information on regional and thematic competences as well as points of contact to establish systematic and effective referrals among CSOs, equality and anti-discrimination bodies.

- Both specialist and non-specialist CSOs, equality and anti-discrimination bodies should establish a formalized process for data exchange and client referrals among each other. This should include an agreement between them to standardize how and what kind of data can be forwarded while respecting victims’ rights and data protection laws. CSOs, equality and anti-discrimination bodies should also internally aim automated processes to seek victims’ permission for client referrals.

- Provide continual trainings to sensitise and raise awareness on a victim’s centred approach and of hate crime victims’ special needs across law enforcement and criminal justice system professionals. In addition, provide training budget for CSOs to ensure quality standards in victim support are continuously met.

- Create single points of contact or liaison officers in law enforcement to ensure that victims can be referred to, gather information from and/or report their case to specially trained and committed police officers.[64] Currently, the training approach of the MoI foresees a mainstreaming of the topic rather than a specialisation. That is for many reasons a valid strategy. Still, to build a network of single contact points for specialist and grassroots CSOs has its advantages when referring victims of hate crime (or accompanying when reporting).

- Implement a legal basis for an automated referral system of hate crime victims between law enforcement and victim support organisations. Consult specialist CSOs working in the field of hate crime victim support to decide on the form of such automated referrals (e.g., similar to the existing system in the field of domestic violence or an opt-out model, etc.).

- Adopt a national strategy or action plan to combat hate crimes in order to provide legal frameworks and financial support to formalise the hate crime referral mechanisms needed to adequately support hate crime victims. For example, this could be established in the form of an inter-ministerial working group, led by the Ministry of Interior.

- Systematize hate crime data collection and data exchange practices across civil society organisations, equality and anti-discrimination bodies as well as across public and civil society stakeholders. In order to enable joint reporting, an agreement on a set of data that is collected by all cooperating organisations should be concluded. For example, data could be streamlined from grassroots to specialist organisations, then collected by the Ministry of Interior and fed into the annual hate crime reports.

- Institutionalise cooperation and coordination across law enforcement/the Ministry of Interior, the criminal justice system/Ministry of Justice and CSOs, equality and anti-discrimination bodies.

- Launch public information and awareness campaigns on hate crimes. Create a multi-lingual and accessible website, app or similar single point of information on how and where to report incidents as well as all legal advice and counselling service providers available.

- Establish regular victimisation surveys to gather data about unreported hate crime.

Bibliography

Nicoletti/Starl (2017), Hate Crime in der Steiermark, Erhebung von rassistisch und fremdenfeindlich motivierten Straftaten in der Steiermark und Handlungsempfehlungen, https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.steiermark.at/cms/dokumente/12583161_137267669/0717841f/2bericht.pdf [accessed 11 January 2023].

Bundeskanzleramt (undated), Kampf gegen Antisemitismus, https://www.bundeskanzleramt.gv.at/themen/kampf-gegen-antisemitismus.html [accessed 11 January 2023].

Bundesministerium für Inneres (undated), Hate Crime Vorurteilsbedingte Straftaten, https://www.bmi.gv.at/408/Projekt/start.aspx [accessed 11 January 2023].

Bundesministerium für Inneres (2022), Hate Crime in Austria, Annual Report 2021, https://www.bmi.gv.at/408/Projekt/files/552_2022_Hate_Crime_Report_Englisch_V202211118webBF.pdf [accessed 11 January 2023].

Bundesministerium für Justiz (2016), Erlass vom 30. Mai 2016 über ein Bundesgesetz, mit dem die Strafprozessordnung 1975, das Strafvollzugsgesetz und das Verbandsverantwortlichkeitsgesetz geändert werden (Strafprozessrechtsänderungsgesetz I 2016), BMJ-S578.029/0006-IV 3/2016, https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokument.wxe?Abfrage=Erlaesse&Titel=Erlass+vom+30.+Mai+2016+über+ein+Bundesgesetz%2c+mit+dem+die+Strafprozessordnung+1975%2c+das+Strafvollzugsgesetz+und+das+Verbandsverantwortlichkeitsgesetz+geändert+werden+(Strafprozessrechtsänderungsgesetz+I+2016)&VonInkrafttretedatum=&BisInkrafttretedatum=&FassungVom=08.01.2023&Einbringer=&Abteilung=&Fundstelle=&GZ=&Norm=&ImRisSeitVonDatum=&ImRisSeitBisDatum=&ImRisSeit=Undefined&ResultPageSize=100&Suchworte=&Position=1&SkipToDocumentPage=true&ResultFunctionToken=d51b3a2b-dc33-406b-af26-1d4f172f671b&Dokumentnummer=ERL_BMJ_20160530_BMJ_S578_029_0006_IV_3_2016 [accessed 11 January 2023].

Die österreichische Justiz (undated), Opferhilfe und Prozessbegleitung, https://www.justiz.gv.at/home/service/opferhilfe-und-prozessbegleitung.961.de.html [accessed 11 January 2023].

FRA (2018), Being Black in the EU, https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2018/being-black-eu [accessed 11 January 2023].

Fuchs (2021), Hate Crime in Österreich, https://www.bmi.gv.at/408/Projekt/files/hc_pilotbericht_final_druck.pdf [accessed 11 January 2023].

Haider (2020), Zur Erfassung und Verfolgung von Hate Crime in Österreich, Journal für Strafrecht 7, 398-413.

Hart/Painsi (2015), LGBTI Gewalterfahrungen Umfrage, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/lgbti_gewalterfahrungen.pdf [accessed 11 January 2023].

ORF.at (2014), Der Fall Bakary J. – Eine Chronologie, https://wien.orf.at/v2/news/stories/2678375/index.html [accessed 11 January 2023].

OSCE/ODIHR (undated), Hate Crime Reporting, Austria, https://hatecrime.osce.org/austria [accessed 11 January 2023].

Romano Centro (2017), Antigypsyism in Austria, Incident documentation 2015-2017, https://www.romano-centro.org/images/zeitschrift/ag2017/index.html#page=1 [accessed 11 January 2023].

Schönpflug/Hofmann/Klapeer/Huber/Eberhardt (2015), “Queer in Wien”, Stadt Wien Studie zur Lebenssituation von Lesben, Schwulen, Bisexuellen, Transgender und Intersex Personen (LGBTIs), https://www.wien.gv.at/menschen/queer/schwerpunkte/wast-studie.html [accessed 11 January 2023].

Schweppe/Haynes/ Walters (2018), Lifecycleof a Hate Crime: Comparative Report, https://www.iccl.ie/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Life-Cycle-of-a-Hate-Crime-Comparative-Report.pdf [accessed 7 May 2023].

[1] This text is adapted from Perry, J. (2019) ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Europe’. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan, https://www.facingfacts.eu/european-report

[2] As a general rule, Facing all the Facts uses the internationally acknowledged, OSCE-ODIHR definition of hate crime: ‘a criminal offence committed with a bias motive’.

[3] In terms of its conceptual scope, the research focused on hate crime recording, data collection and victim referrals, and excluded a consideration of hate speech and discrimination. This was because there was a need to focus time and resources on developing the experimental aspects of the methodology such as the workshops and online system map. International and national norms, standards and practice on recording and collecting data on hate speech and discrimination are as detailed and complex as those relating to hate crime. Including these areas within the methodology risked an over-broad research focus that would have been unachievable in the available time. In addition, the Austrian system is further developed in terms of hate speech victims support than the respective support system for victims of hate crime.

[4] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a detailed description of the research theory and approach of the project.

[5] Network countering hate crime: https://hatecrimekontern.at/. The network consists of different NGOs, CSOs, Community organisations and public institutions.

[6] For facilitation purposes in this report, other anti-discrimination bodies, which to our knowledge are only partly public authorities, are treated as CSOs.

[7] See the Methodology section of the European Report for agenda and description of activities.

[8] See the Methodology section of the European Report for a full description of the research methodology.

[9] See the annex for more details and further references.

[10] E.g., in the course of the EU-Funded project Stand up for victims rights, https://standup-project.eu, and the network countering hate crime, see FN 3.

[11] See the FATF Thematic report, https://www.facingfacts.eu/european-report/.

[12] ORF.at (2014).

[13] Romano Centro (2017), pp. 10 and 14-15.

[14] FRA (2018).

[15] FRA (2018), p. 22.

[16] FRA (2018), Data Explorer.

[17] FRA (2018), pp. 31-32.

[18] FRA (2018), p. 35.

[19] This text is adapted from Perry, J. (2019) ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Europe’. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan, https://www.facingfacts.eu/european-report

[20] See Methodology section of the European Report for further detail.

[21] Schweppe et al. (2018), p. 67. The extent of this ‘disappearing’ varied across national contexts, and is detailed in national reports.

[22] See appendix.

[23] Based on interviews with individual ‘change agents’ from across these perspectives during the research.

[24] This text is adapted from Perry, J. (2019) ‘Connecting on Hate Crime Data in Europe’. Brussels: CEJI. Design & graphics: Jonathan Brennan, https://www.facingfacts.eu/european-report

[25] For a full description of the main stakeholders included in national assessments, and how the self-assessment framework relates to the ‘systems map’, see the Methodology section of the European Report.

[26] ODIHR Key Observations, https://hatecrime.osce.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/KEY%20OBSERVATIONS%20as%20of%202020HCR.pdf; this methodology could also be incorporated in the framework of INFAHCT self-assessment, as described on pp. 22-23 here: https://www.osce.org/odihr/INFAHCT?download=true.

[27] See Methodology section of the European Report for instructions.

[28] The process to implement such a system has been initiated by ZARA more than 2 years ago with some stakeholders. However, more coordination and the inclusion of additional stakeholders is needed.

[29] See the recommendations section for a more detailed discussion of this topic.

[30] Haider (2020).

[31] Fuchs (2021), pp. 59-69.

[32] OSCE/ODIHR (undated).

[33] Respondent nr. 12.

[34] Respondent nr. 9.

[35] Respondent nr. 8.

[36] Respondent nr. 10.

[37] “Gemeinsam Sicher” is the community policing project of the Austrian police.

[38] Respondent nr. 6.

[39] Respondent nr. 12.

[40] Respondent nr. 8.

[41] Respondent nr. 10.

[42] Respondent nr. 6.

[43] Respondent nr. 8.

[44] Respondent nr. 10.

[45] Respondent nr. 12.

[46] Respondent nr. 10.

[47] Respondent nr. 16.

[48] Secs 25 para 3, 38a para 4, 56 para 1 subpar 3 of the Austrian Security Police Act.

[49] Respondent nr. 16.

[50] Respondent nr. 8.

[51] Respondent nr. 14.

[52] The list is intended to serve as a starting point to formalize and foster referral practices.

[53] Antidiskriminierungsstelle Salzburg, https://www.antidiskriminierung-salzburg.at/index.php?id=5.

[54] Antidiskriminierungsstelle Steiermark, https://www.antidiskriminierungsstelle.steiermark.at. The anti-discrimination office Styria also operates the BanHate app, where hate crimes and online hate speech can be reported: https://www.banhate.com.

[55] Dokustelle Islamfeindlichkeit & antimuslimischer Rassismus, https://dokustelle.at. The website provides for online reporting.

[56] Initiative für ein Diskriminierungsfreies Bildungswesen (IDB), https://diskriminierungsfrei.at. The website provides for online reporting.

[57] Antisemitismus Meldestelle, https://www.antisemitismus-meldestelle.at. The website provides for online reporting.

[58] 24-Stunden Frauennotruf, https://www.wien.gv.at/menschen/frauen/beratung/frauennotruf/.

[59] Wiener Antidiskriminierungsstelle für LGBTIQ-Angelegenheiten (WASt), https://www.wien.gv.at/kontakte/wast/.

[60] Weisser Ring, https://www.weisser-ring.at; Opfernotruf, https://www.opfer-notruf.at. The latter website provides for online reporting.

[61] ZARA, https://zara.or.at/de. The website provides for online reporting.

[62] Other relevant projects on related topics include: Stand Up for Victims’ Rights, Policy Brief, https://standup-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/A4_policy_brief_standUP_EN.pdf; Enhancing Stakeholder Awareness and Resources for Hate Crime Victim Support (EStAR), Practices of Civil Society and Government Collaboration for Effective Hate Crime Victim Support, https://www.osce.org/files/f/documents/4/2/514165.pdf; European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, Hate crime recording and data collection practice across the EU, https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2018-hate-crime-recording_en.pdf.

[63] https://www.facingfacts.eu/findings-iv/

[64] See FRA, Hate crime recording and data collection practice across the EU, https://fra.europa.eu/en/publication/2018/hate-crime-recording-and-data-collection-practice-across-eu for different models.

About the author

Isabel Haider is an independent consultant and a researcher at the Department of Applied Sociology of Law and Criminology at the University of Innsbruck. Her research focuses on Hate Crime, Gender-based Violence Against Women/Femicide and Policing. Previously, she served as a consultant to the European Network Against Racism (ENAR) and the EStAR: Enhancing Hate Crime Victim Support project of the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions.

About the co-author

Amina El-Gamal has an MA in Development Studies. She worked and researched on intersectionality, discrimination, and power structures. Currently, she is the coordinator of (trans-)national cooperation at ZARA – Civilcourage and Anti-Racism-Work in Austria focusing on (online) hate speech and hate crime and coordinating the national Network Countering Hate Crime.

About the editor

Joanna Perry is an independent consultant, with many years of experience in working to improve understandings of and responses to hate crime. She has held roles across public authorities, NGOs and international organisations and teaches at Birkbeck College, University of London.

About the designer

Jonathan Brennan is an artist and freelance graphic designer, web developer, videographer and translator. His work can be viewed at www.aptalops.com and www.jonathanbrennanart.com

Acknowledgement

The Facing Facts Network is grateful to all those who participated and generously contributed their time to this project. Many thanks are extended to ZARA – Civil Courage & Anti-Racism Work and the Austrian Ministry of the Interior.

This report has been produced as part of the project Facing Facts Network which is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme (2021-2027) of the European Union.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme

Facing Facts is co-funded by the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values Programme